BERKELEY, Calif. -- California offensive coordinator Tony Franklin sometimes wonders what it would feel like to join a student protest on campus.

Every day, Franklin intentionally walks through the middle of the Berkeley campus to see what Cal students are protesting next. He usually sits and reads a book near the protests, soaking in the energy of students who have something to tell the world, even if Franklin may disagree with what's being said.

Franklin considers Berkeley home. That's no misprint. Franklin, a longtime Southerner raised ultra-conservative, can envision living in ultra-liberal Berkeley long after he's done coaching.

"I'm at peace," Franklin said in March at his office. "This is the first place as an adult that I've felt like I'm at home. It's the first place I've ever been in my life that they don't see through their eyes what other people see. They don't see color. They just embrace different. For me, I'm a weirdo and I don't feel weird here. I feel normal."

In the controlled and uptight world of college football, there is nothing normal about this conversation during Cal spring practice between a reporter and Franklin. How many college football coaches express embarrassment about not voting for Barack Obama in 2008? How many openly discuss how his children's values changed him from a Republican to a hard-core Democrat? How many have on their desk the book Guantanamo Diary, which tells the story of a detainee at Guantanamo Bay since 2002 who has not been charged with a crime?

"I want to find out why," Franklin said. "I don't know yet, but [it used to be] I didn't want to know. It used to be, 'By God, if they're holding him, he must have done something and he deserves to be there and we're protecting our country.' And now I want to know because I don't believe our politicians are right. I think they're wrong most of the time, and it makes me sick to my stomach and embarrassed a lot of times."

It's probably not hyperbole to say there has never quite been a football coach like Franklin. He marches to a different beat.

Franklin is the politically incorrect coach who, for various reasons, has never stayed at a coordinator job longer than three years during 11 seasons calling college offenses. He jokes he could write a book on how to get fired with a 5-2 record thanks to his "horrible" offense at Auburn in 2008, and you actually think he might one day write that book.

This is Franklin's third year at Cal, which improved to 5-7 last season with an offense ranked 10th nationally in scoring. But the Bears haven't been to a bowl since 2011. Now, in an unorthodox move straight out of Franklin's playbook, he's adding running backs coach to his duties that already include offensive coordinator and quarterbacks coach.

Franklin is the accused whistleblower who once thought he would be blackballed from college football forever after being accused of providing the NCAA information that brought down Hal Mumme and put Kentucky on probation. Franklin wrote a book to clear his name and sued Mumme and Kentucky.

Franklin is the football entrepreneur who, needing money while blackballed, created the Tony Franklin System and took a risk by running up-tempo offense long before going fast was cool. He holds seminars and weekly conference calls during the season with 50 to 100 high school coaches who are clients. Franklin admits he's their "guinea pig" because he's the one who experiments with radical plays and concepts.

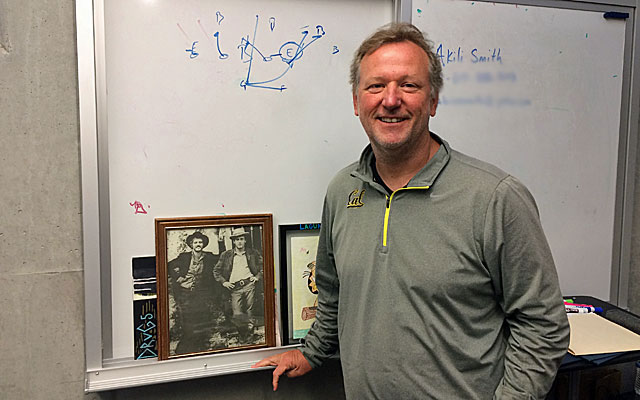

But if only football defined Franklin, he would be disappointed. On the wall of Franklin's office rests a framed photo of Robert Redford and Paul Newman as the Sundance Kid and Butch Cassidy. He has carried it everywhere since 1984, when he left Murray High School in Kentucky.

"It always reminded me that when you leave this world, you shouldn't have any bullets left in your gun," Franklin said. "It's the final scene and you know they're going to die. That summarizes my life. I've always been a risk taker. Some have worked, some haven't. When I'm finished, I don't think I'll have any regrets."

Regrets? Yes, Franklin carries some of those. Now 57 years old, Franklin is old enough to be a grandfather of two young boys -- "I told them they can't call me Gramps, they can call me Coach" -- and he views the world differently now than when he was younger. More on those regrets later.

Because Franklin's biggest regrets aren't the ones you might think. Franklin badly failed in his one season in the national spotlight, but he doesn't regret trying. And he no longer holds a grudge against Tommy Tuberville's longtime assistants for not buying into his tempo offense at Auburn. "I don't blame those guys," Franklin said. "They were worried about their jobs. It was just a horrible fit."

Franklin also shows no regrets that he has not been a college head coach. He doesn't think he can be a good CEO or interact well with boosters.

Close friend Rush Propst, a high school coach in Georgia, has argued with Franklin that he's already a CEO of his Tony Franklin System. "He would be a great head coach," Propst said.

But Franklin is refreshingly candid in how he views himself. He believes it's much easier to be who he is as a coordinator than a head coach. Instead of worrying about what he says publicly or what happens if he's seen drinking a beer by a fan base that frowns upon alcohol, Franklin can be himself.

There's something to staying true to yourself. Plus, it's not like Franklin is hurting for money with a $572,500 salary in 2014. (Franklin made $205,200 in his final year at Louisiana Tech in 2012.)

"I've always been somebody who did not really want to be politically correct," Franklin said. "Usually if you ask me a question, you get an answer that's what I'm actually thinking vs. what I should be saying. I love being around young people -- their energy, their honesty, their innocence. Sometimes I may not play as well with adults. I've never felt being a head coach would be a good fit for me."

Franklin was a head coach at three different high schools many years ago. Also, in a story fitting for his unique coaching life, he coached the Lexington Horsemen of the National Indoor Football League in 2003 at Rupp Arena. Allow Franklin to describe how that head-coaching stint went.

"To this day, it's the most fun I've ever had coaching in my life to coach a bunch of guys that played for me at Kentucky," Franklin said. "Instead of doing curfew, you loaded up the bus for road trips with beer and dropped them off at the bars, and the next day they showed up for the game. We had a lot of fun."

Franklin's passion in football is teaching. In addition to the photo of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Franklin keeps a painting of Peyton Manning hung in his office.

"I never wanted to buy sports art. Zero interest in it," Franklin said. "But every quarterback thing I do is based on Peyton Manning -- every drill, every technique, every thought process."

Cal head coach Sonny Dykes envies Franklin -- they're old friends from their Kentucky days -- and is pretty sure the feelings aren't mutual. Don't get Dykes wrong: He knows his role and his $1.8 million salary are predicated on being a CEO. But Dykes often misses the days that Franklin can enjoy simply coaching football.

"You get into the business because you love to coach football and you're really just a manager in a lot of ways, which is OK. I enjoy it," Dykes said. "But you do just miss sitting in a dark room trying to figure out how to move the football. I don't think he envies me much at all."

Franklin describes his coaching career this way: "I love fixing stuff that's broke." The only time Franklin has been a college offensive coordinator at the same school for three years came from 2010-12, when his third year with Dykes at Louisiana Tech produced the nation's most prolific offense in scoring (51.5 points) and total yards (577.9).

Louisiana Tech's 2012 season was the year Franklin started tagging a pass route to every running play. Franklin learned the concept at one of his seminars from West Virginia coach Dana Holgorsen and was blown away by how it helped tempo offenses.

"I went to my seminar the next year and said, 'Please, let's keep this within our family. Don't tell anybody. Maybe we can get five years out of it,'" Franklin recalled. "In 2012, maybe five to 10 college teams were doing it with full-route concepts. Now it's half of college football doing it. We got two good years out of it."

This is Year 3 for Franklin and Dykes at Cal after 1-11 and 5-7 seasons in which the defense allowed 42.8 points per game -- the worst among all major conference teams. Franklin knows what a third year means: "As a coordinator, Year 3 is a year you need to win. I think we need to have a winning season and go to a bowl game. I'll be extremely disappointed if we don't."

Cal returns quarterback Jared Goff, who last season ranked 21st in pass efficiency (35 touchdowns, seven interceptions) and fifth in yards per game (331.1). Franklin is so high on Goff -- "special" is the word he uses -- that he says his Cal quarterback has a chance to be the best Franklin has ever been around. Franklin was at Kentucky with Tim Couch, the NFL's No. 1 pick in 1999.

In a unique twist this spring, Franklin added running backs coach to his duties. Franklin lobbied Dykes to take on the extra role when Cal's staff got reshuffled.

"It's easy to do," Franklin said. "Running backs and quarterbacks complement each other because we need to get our ball more in the throwing game. I promise you our guys will catch more balls than anybody in our league coming out of the backfield."

As part of Franklin's up-tempo offense, the Bears ran 81.3 plays per game while often putting up video-game numbers. But they also allowed 28 sacks (82nd in the country) and Dykes wants the quarterbacks and running backs to be on the same page to improve protection and check-down throws.

How exactly does Franklin serve as both quarterback coach and running back coach at practices? Franklin insists it's easy because practices go so fast and most of the teaching happens in film rooms.

"We're together 95 percent of practice," Franklin said, noting that only one segment at a mid-March practice would occur with quarterbacks and running backs on a different part of the field.

As much as Franklin loves to coach, life is different in Berkeley. Football is life in the deep South, where Franklin lived all his life. Berkeley is a place where Franklin can mingle into the crowd while walking to his apartment after a home loss and Cal fans won't ever say a negative word, if they even know who he is.

"But you'll listen to them talking about the game or the band or weather," Franklin said. "It's just fun and different [than the South]. Doesn't mean one of them is right, one of them is wrong. It definitely fits me better here."

Now about those regrets. Franklin regrets his old political beliefs and his view of the world for his entire life. (Did we mention Franklin isn't your typical college football coach?)

Franklin actually came to these realizations not in Berkeley, but while in Alabama coaching at Troy in 2007 as Obama ran for president. Franklin, who grew up with "parents who didn't see color" in a Southern Baptist home in Princeton, Ky., explains that conversations with his daughters during Obama's first campaign "taught me I was wrong."

"You grow up and you're taught by your parents and people in the community and you learn that culture, and somewhere in life you have to embrace who you are vs. what you grew up as," Franklin said. "It took my kids, who were so much smarter than me and so much more forgiving than me, to educate me, and that's hard to believe when you're a history teacher and political science teacher in high school for 16 years as I was.

"I think most of us who grew up in my era, you had a book and you had a teacher who taught you what was in the book and you believed it. When you think about the Constitution and if you interviewed most conservative people in our country and ask them about our forefathers, most people you ask in the South, they'd say those people were all religious people. And if you go back and look at our forefathers, you find out they were not and strongly opposed it."

Franklin says he wanted to vote for Obama in 2008 but didn't because of a conversation with children of a deceased friend in Alabama. "They convinced me to vote for John McCain and I did, and I was wrong," Franklin said. "I was embarrassed I didn't vote for Obama in the first election. In my heart, I knew I wanted Obama to win."

In the liberal world of Berkeley, Franklin finds he has more friends outside of football than ever in his adult life. Franklin intentionally doesn't socialize much after hours with other Cal coaches. Franklin and his wife Laura initially met friends by eating out almost every night and through Alisha Valavanis, Cal's former assistant athletic director for development and now the president/general manager of the WNBA's Seattle Storm.

"The good thing about Berkeley is wherever you go, nobody knows where you coach and they don't care," Franklin said. "Sure, they might have a conversation about it -- maybe. But they'd much rather have a conversation about Syria."

Franklin was out of town recruiting last December when demonstrators protested in Berkeley. They were rallying against recent grand jury decisions involving the shooting death of a black man by a white police officer in Ferguson, Mo., and the death of a black man put in a chokehold by a New York officer. They also protested the death of a transgender woman who died in police custody in Berkeley, and the alleged abduction of 43 students by police in Mexico.

Protesters in Berkeley "kicked out the front door of the apartment complex where I live at," Franklin said. "My wife and daughter were here and they were able to be around all this and to see how amazing it is for people to come together for a belief, and to see how sometimes they go too far. Or in this case, the 1 percent -- thugs -- who do something stupid anyway. But I love that about being here. I love if something's going on, they're going to express their opinion."

Franklin even wonders what it would take for him to participate in a Berkeley protest. He hasn't -- at least not yet -- out of respect for his head coach, Dykes.

"Even if I didn't want to represent him, it could be perceived that way and I would never want to put him in that position that your offensive coordinator just got arrested on campus for protesting something that maybe he doesn't believe in," Franklin said. "It's not to say I wouldn't if I felt strongly enough about it. Right now, I can't see myself doing something that would put him at risk."

This is quintessential Franklin: Extremely opinionated, politically incorrect and intensely loyal. In a college football coaching community filled with so much black and white, Franklin not only accepts gray in life, he questions how gray became gray.

A 90-minute interview with Franklin is unlike any that regularly get conducted with a football coach. And that's the point.

"I tell my friends and my family that the last thing in the world I would ever want is that when I pass away for people to stand over me -- well, I'll be cremated so they won't be standing over anything -- but to be at a service and talk about how good a coach I was," Franklin says. "I would be insulted if that was the primary part of the conversation. I love the influence I've been able to have on young people to go out and change the world. Because I haven't changed the world, but they do."