In 2018, it's trendy to talk about saving baseball.

As strikeouts increase, nine innings drag and Major League Baseball looks enviously at the NFL's revenue and the NBA's spotlight, everyone's looking for a way to change the culture of the game.

Shorten this! ... Ban that! ... Market this!

In 1918, the problems were different. And the culture changed itself.

Scandal. War. Nationalism. Segregation. They all had starring roles in what may have been the most influential stretch of baseball in the history of the sport. Exactly 100 years after that season's World Series, the first and last of its kind to be played entirely in September, the ripple effect is still clear as day.

For women, for African Americans, for gamblers, for soldiers, for patriotism and for this country, baseball in 1918 was a game-changer.

Guns over gloves

A shade over 100 years after the War of 1812 left the United States Capitol burned and battered, President Woodrow Wilson walked into D.C.'s domed building to address Congress. His request, on April 2, 1917: Declare war on Germany.

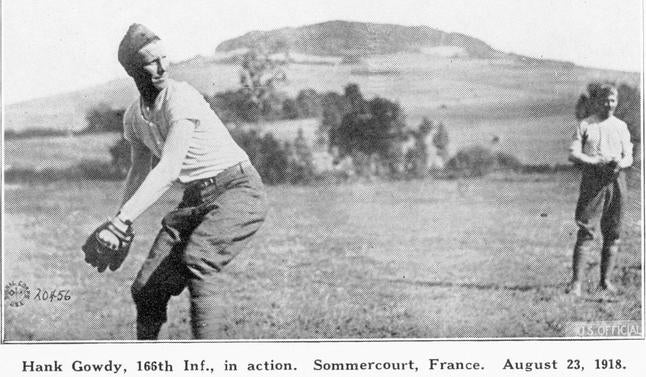

Ensuing preparations, which The History Channel calls "the largest war-mobilization effort in the country's history," involved the Selective Service Act of 1917 -- the draft. With only 100,000 or so troops at its disposal, the military began "plucking able young men from every walk of life," as Kansas City's National World War I Museum and Memorial explains.

The NHL would not arrive until six months later. The NFL wouldn't come until 1920. The NBA would show up even later, in 1946. But MLB was already in its teens, and baseball carried on as usual.

Until Newton D. Baker, that is.

By July 1918, Army General Enoch Crowder convinced Baker, the U.S. Secretary of War at the time, that any draft-eligible men employed in "non-essential" jobs should be forced to choose: "Enlist to help stateside, or risk going to the front lines of Europe," according to This Great Game, which chronicles America's Pastime. It was do or die -- or more like "do and/or die." Sign up to support the war, or risk going to fight it yourself.

And then Baker brought the curveball. Baseball, with all its American glory, was deemed "non-essential." Crowder supervised the drafting of roughly 2.8 million men for the war, and around 250 of them came from MLB -- an average of more than 15 players per team at the time. The cabinets had been raided.

No one was thinking about how a global war would evolve the game at that moment. They were wondering: Will baseball survive?

A shortened season

MLB may have been older than the other major sports leagues back then, but it was still relatively young, having come together under a National League and American League agreement in 1903. The NFL at least had two decades under its belt before World War II came calling. Here, in 1918, a growing sport was forced to act on the fly.

"When Secretary Baker decided that baseball was not an essential occupation, that really handicapped them," says Doran Cart, senior curator for the National WWI Museum.

And so began the season, postseason and World Series with maybe the most dramatic circumstances ever.

The American League recommended a full shutdown, according to the Baseball Hall of Fame, but the National League resisted. So with hundreds of players, including legends like Ty Cobb, Christy Mathewson and "Shoeless" Joe Jackson, enlisted across Western Europe, both sides agreed to hurry the end of the season.

Baseball-Reference.com indicates that between 23 and 27 games were removed from every team's 1918 schedule. By early September, MLB was ready for the (non-)October Classic.

That Series began Sept. 5 between the Boston Red Sox and Chicago Cubs, at Chicago's Comiskey Park.

Boston was without its manager Jack Barry, who had enlisted, so team executive Ed Barrow took his place, complete with a roster depleted by the draft. Player numbers were so sparse, in fact, that Barrow was forced to play his top pitcher in the outfield between starts. That pitcher just happened to be a 23-year-old Babe Ruth.

And while Ruth would power the Sox to a series win, Boston's last until 2004, even his future as an unmatched New York Yankees icon wasn't as lasting as what else occurred at Comiskey Park.

The birth of an anthem

A U.S. military band was on hand for Game 1 of the 1918 World Series, and during the seventh-inning stretch that Thursday evening, it played an impromptu rendition of "The Star Spangled Banner."

In the months leading up to the game, President Wilson had begun to elevate "propaganda and censorship" in order to promote wartime loyalty among Americans, according to Boston University professor Christopher B. Daly. So the song, which had recently been instituted as a requirement for military events, was already a tool in a fight for patriotism when it surfaced at the Series.

"It was kind of being forced on people in other venues before it was sung at the ballpark," says Cart, of the WWI Museum. "There was quite a bit of control over American behavior by the Committee on Public Information, which was created by Woodrow Wilson. In 1917, one of the leading ministers at the time, A.J. Muste, wrote that the custom of having people rise to sing 'The Star-Spangled Banner' at plays, operas and other events was right. It was forced on those who disliked the practice."

Still, America was at war. If ever there was a time to grip the stars and stripes, it was in 1918, at a baseball game, where the absent stars of the diamond had been turned into heroes of war. Call it pride. Call it patriotism. Call it American spirit. When that band started playing, and when Red Sox third baseman Fred Thomas, who was playing while on leave from the U.S. Navy, arose in a military salute, everyone followed suit. Players turned to face a flying flag. Hands went to hearts. And the fans soon followed.

"A thunderous applause at the song's end was far greater than that which greeted any of the athletes that evening," the WWI Museum says.

It took another 13 years for "The Star-Spangled Banner" to become America's national anthem, as designated by Congress. But it was at the culmination of a war-torn 1918 baseball season where the tradition began. It continued each day of the Series, and before long, it expanded to all Red Sox home games, all of MLB and so forth. Propagandized or not, it was America's pastime.

Doorways to equality

How American is baseball? The same 1918 season and World Series that became as much a "U-S-A" chant as an actual sporting event coincided with the boil of a cultural melting pot. For every Fred Thomas saluting out of respect, there may have been just as many Woodrow Wilsons smiling at the sight of conformity under the flag -- a patriotic pursuit that could infiltrate even escapism as trivial as baseball. And yet while the Wilsons of America were smiling at the anthem's arrival in the World Series, baseball's displaced men and women were busy forging their own revolutions from afar.

There were other wartime side effects on the home front, to be clear. One such example: Gambling. Heavy horse usage in World War I prompted the government to temporarily shut down all race tracks, so "bookies really moved over to the ballparks," as Cart says. Since "Americans are famous for betting on anything," baseball quickly drew business. That skyrocketed MLB's popularity -- "second only to horse racing" -- but also led to rumors of both a "fixed" 1918 World Series, plus the 1919 Black Sox scandal of the same nature.

Outside the birth of the anthem tradition, however, nothing may have exploded from 1918's circumstances more than the grassroots of women and African Americans in baseball.

Black men were not included in the official counts of how many pro baseball players served in WWI, according to Cart, since the armed forces were still segregated at the time. Jackie Robinson also wouldn't break MLB's color barrier for almost another 30 years. Hundreds of thousands of African Americans enlisted in total for the war effort, however, and the racial mishmash that followed led to progress on the civil rights' front.

"These guys had to have all been affected by who they saw overseas," Cart says. "There were these very professional teams that the African-American units were forming overseas, with some really top players, and that was really difficult for them to come back to America and not play, which led to the creation of the Negro leagues. There were some semi-pro teams before they went overseas, but they came back and wanted to contribute in the same way that others did."

All sides were touched. Cart's favorite example here: Branch Rickey, the Brooklyn Dodgers president who signed Jackie Robinson in 1947. Rickey was in the Army Chemical Warfare Service during World War I, serving in France, where he would've seen plenty of comrades who looked different than himself.

Women, on the other hand, made their own trot around the historical base paths at the same time. When double the number of MLB players were drafted for World War II years later, Chicago Cubs owner Philip K. Wrigley commissioned the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League to keep the sport alive. That league opened doors for women in pro sports in general, but it also probably wouldn't have come to fruition if not for baseball's place in the midst of war and 1918's MLB disarray.

"After the Armistice on the Western Front," Cart says, "there were baseball teams formed of women on the Army Nurse Corps and of the YMCA women volunteers, and they barnstormed around occupied Germany, they were met by enthusiastic crowds and taught women workers in England how to play baseball. (So) the women's league during World War II, they already had a precedent for that. It wasn't created out of the ground."

A timeless influence

To this day, the 1918 World Series was the earliest ever played in a major league season. And yet its games, the season that preceded it and the international clouds that surrounded it? They are timeless. The influence was felt when the sirens rang once more in 1941, this time with President Franklin Roosevelt insisting in a National Archives-preserved letter that baseball "keep ... going" in the face of World War II.

And their influence is felt 100 years later, in a country whose cultural dynamics have never been more diverse.

The irony -- or tragedy -- of repeated history isn't hard to spot. Here in 2018, as the National WWI Museum prepares centennial celebrations reflecting on the 1918 World Series, the current U.S. president has repeatedly suggested that professional athletes who've used the national anthem to protest ongoing racial inequalities "shouldn't be in the country" if they aren't "respecting" the flag. Chief among his targets: Former NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick, whose legacy, like baseball's women and minorities before him, isn't so much playing an American sport as it is using it to provoke change.

It's easy to see, then, that 1918 is as much a picture of lessons to be learned as it is paths already paved.

Yes, baseball in the 21st century has its problems, much like the world it inhabits.

But the next time anyone says baseball's culture needs a face lift, just remember: 1918 will give it a run for its money.