Almost six months ago to the day, on July 6, 2015, the NCAA sent a missive to every Division I men's basketball coach essentially preparing them for what was coming: The rules are substantially changing, so you better change, too.

Here we are on Jan. 7, and somehow, some way, coaches and players alike have seemingly, deftly adapted without much lag. It's an unacknowledged phenomenon. Scoring is up, possessions are up and the game is squiggling toward a more fluid existence. For most, the grand takeaway at the midway point of the 2015-16 season: The rules changes are working and results are increasingly positive.

And that's something a problem.

Because it shouldn't be this easy.

Remember how it was supposed to take a couple of years to adjust? The way the mighty NBA needed a few seasons to knead out its slogging tendencies after the turn of the century? Yet here's college basketball, a sport with worse athletes and plenty more challenges, seemingly flipping a switch overnight and masterly adjusting to the greatest offseason amendment to the sport's rulebook in the modern era.

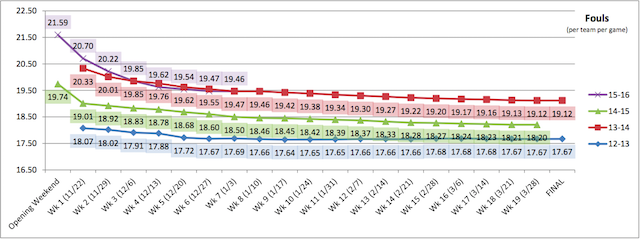

There is something amiss. One of the most powerful men in the sport, Dan Gavitt, knows it and is uneased with one major facet of the overhaul. Fouls are still not being called consistently and correctly across the board.

"Where I’m a little concerned that we may not be where we need to be is reducing physical play area," Gavitt, who is the VP of men's basketball championships, said. "There haven’t been as been as many fouls as we figured there would be. On the surface, maybe that’s a good thing, but on the curve, tracking this year versus the past few years, there’s a natural progression to fewer foul as the season goes on. We’re actually tracking right now behind where we were a few years ago."

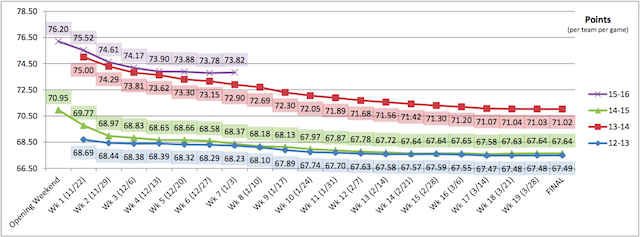

Per KenPom.com's figures, college basketball's 30-second shot clock has helped lift the average possessions per game this season to 70.4. up from 66.5 in 2014-15. In 2013-14, 68.7. The year before that, 67.6.

"The pace is what most of college basketball was looking for when we made these rule changes," Army coach Zach Spiker said. His Black Knights team is top-10 in possessions per game.

On the most basic of levels, this was one half of the mission for college basketball's grand makeover. The other was more subjective: A more entertaining sport induced by freedom of movement and a callback to how the game used to be played, with motion, style and bouncy flex.

"If you adjust with possessions, we’re actually behind in scoring, fouls called per game and percentage," Gavitt told me in December. "I’m trying to look at it from a bigger, broader perspective. We should be doing better than last year."

Last season was among the three worst points-per-game showings for the sport in the past 50 years. (And 2012-13 was the nadir.)

“We’re sounding the alarm here a little bit," Gavitt said. "We have some concern. Good effort, but not there yet. As we lead into the conference season, we need to do a better job, because you come to a point where it’s hard to do that in the middle of conference season. History doesn’t work in our favor in that regard."

Texas coach Shaka Smart's isn't convinced a full fix is coming.

"I don't know that it's possible to call every foul every time the way they're describing, on and off the ball," he said. "The question becomes, Which ones do you call and which ones do you let go?"

Before we go any further, in an effort to understand Gavitt and others' concern and curiosity, let's put on display some of the vital statistics the NCAA tracks and assesses on a weekly basis. Every Monday morning in Indianapolis, powers-that-be with the NCAA take stock of the patterns unfolding in college basketball. CBS Sports obtained the most recent logs. These are the NCAA's figures for all games featuring Division I teams as of Sunday, Jan. 3.

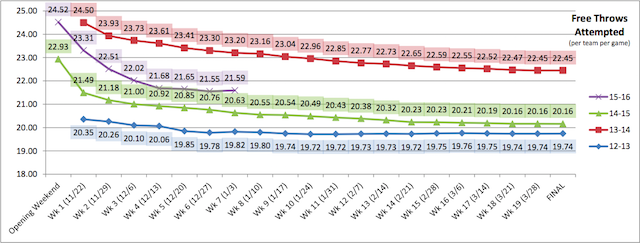

The NCAA attributes 71.5 percent of the scoring increase to pace of play and 28.5 percent to increased offensive efficiency. Free-throw attempts are weirdly down 1.4 percent per possession.

• Points per game: Possessions are up, so points will go up. Simple cause and effect here. The jump from last season to this season right now stands at 5.45 (a 7.9 percent increase). A good shot in the arm for the sport, no doubt. Scoring is also up because steals -- oddly -- are not. It's also unusual that scoring has yet to dip with league play now underway in earnest. There's skepticism from some in the sport that this pattern will hold; it hasn't in previous years. The biggest reason for that is teams play slower in league play, meaning fewer possessions. Thus, fewer points.

• Fouls: Hacks per game are (barely) lower now than they were at the same point in the season two years ago, when the game averaged fewer possessions. Data from the past decade-plus suggests efficiency will rise in conference play as the games get slower, but total fouls will take a dip but that's connected in large part to fewer possessions.

"The thing they've done a better job this year is freedom of movement on the perimeter, but what's benefited us is they've called the rough place," said Purdue coach Matt Painter, whose Boilermakers lead the nation in field-goal percentage defense. "Whereas the last few years it's been an absolute joke how teams have defended and how fouls have been called against our big guys."

Many a college basketball fan can recall the failed attempts in 2013-14 to clear up the block/charge interpretations and reduce physical contact on the perimeter, which led to a massive hike in foul shots attempted. A similar effect was intended for 2015-16, but with a broader scope and clearer initiative. But, as you can see this season, despite more possessions and a directive to call the game tighter in every facet, foul shots are down nearly two per game from two years ago, and not even one full shot up on average from last season, when there were four fewer possessions per game. The scoring increase, unlike 2013-14, hasn't come in big part to more free-throw attempts. On the surface this is good, but in reality it more likely signals a failed effort by officials to call a tighter game.

• Efficiency: See how the points per possession line for 2015-16 is cruising under what 2013-14 brought us? That's what's concerning to many who helped implement the big changes for this season. College basketball's efficiency numbers have been trending up for a long time, yet now we're failing to see a swell in the PPP line despite new protocols designed to give the offense more advantages.

• Turnovers: And shouldn't it stand to reason that more possessions per game should contribute to more turnovers per game? Nevertheless, here we are in 2015-16 with teams taking care of the ball better now than in recent years. A freer game is not leading to a sloppier one -- yet. This season is tracking to be the second safest in modern history. To this point, steal average has gone down, along with blocks and turnovers. For some, this is evidence of more freedom of movement on the floor.

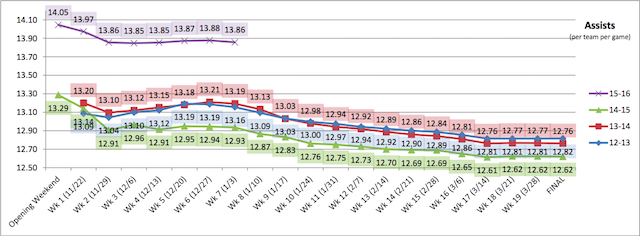

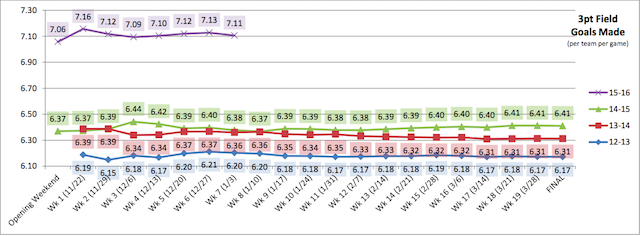

Let's quickly hit on two pieces of really good news: assists are up in a huge way, as are 3-pointers. Again, this is primarily a function of more possessions, but still, more passing and more long balls are better for the enjoyment of the game.

All of this information spurred Gavitt to write the following in a memo to Division I membership in December. CBS Sports obtained the memo, which in part reads:

"When comparing this season’s statistical trends to the 2013-14 season, which was one of the best statistically offensive seasons in the last 15 years, it reveals significant reason for concern. Scoring is actually down about two percent per possession, field goal percentage is down 0.7 percent, and fouls called per possession are down two percent. (Remember the 2013-14 season saw the emphasis made on calling fouls on defenders guarding the ball handler, Rule 10-1.4.) Finally and most concerning of all this season, the average number of fouls called per team per game has fallen from 21.8 to 18.5 (-3.3 fouls) since the first week of the season – a drop of 15 percent in just a month."

You might see a 15-percent drop in a season's five-month period -- not a cliff dive in less than five weeks.

"We want fouls called that are fouls," Gavitt said. "The only other explanation is that coaches and players have adjusted so significantly, and maybe some of that is going on, but not to the level of 15 percent. My sense is we’re doing a pretty good job on the perimeter and illegal screens. If there’s areas for improvement, it’s low-post play, contact off the ball — cutters — because those are harder plays to call."

Fouls happening at nearly the same rate on a per-possession basis is an indication for some that officials are not being diligent enough with new customs. More evidence of that? Coaches aren't complaining -- mostly. A Big 12 coach did supply this quote, but wanted it off the record as to not publicly come off as petulant.

"I still don't think they're calling it the way they said they're going to call it," the coach said. "If there's 100 calls a game, everyone's gonna bitch, people are gonna foul out and it's bad for TV. Go back to the national championship last year. If Wisconsin is allowed to play the way they did all year long in the Big Ten, they probably win the game, but the game was called tighter. Ask Bo Ryan. It was called differently then."

In speaking with more than a dozen prominent coaches around the sport for this story, their two biggest gripes were not being able to call live-ball timeouts and the elimination of the five-second count for closely guarding a dribbler.

Complaints with the calls? Resistance to the new whistle? Not really.

Overall, all coaches I spoke with have embraced the changes. Many are championing them. This is a shock, considering the behind-the-scenes resentment among many of them just two years ago. Gavitt said coaches have been "very quiet" compared to 2013-14.

"There has not been groundswell," he said.

A lack of outcry from the sport's sideline executives is perhaps the most damning evidence of a widespread failure to officiate the game to the fullest extent of the new rules. A few coaches rebuffed this idea by citing 2013-14's block/charge misadventure as adequate prep for this season's sea change.

"They sent out a loud warning and this is how it's going to be," Painter said. "If you want us to ruin games and call 50 fouls, you have a choice. I can't explain the change."

Cincinnati coach Mick Cronin also offered an explanation, saying coaches and players practice every day, watch film year-round and study the craft. Officials only get their reps in when they can actually call games, so it stands to reason coaches and players have adjusted whereas the zebras are still lagging behind.

"They change the rules on us, and I'm practicing every day and adjusting to the changes, and you're not, you're just going to show up at the game and now you have to adjust," Cronin said. "Who's the adjustment going to be harder on? See, the officials don't practice every day. Unlike the pros, they're not required to watch film and answer for every call they make."

Cronin is also steadfast on the game being called naturally. He strongly fights back on the notion of fouls needing to go up just because new rules are in place.

"What shouldn't be happening is anybody calling a referee crew after a game and saying, 'Why do you only have 16 fouls in that game?'" Cronin said. "What if both teams played zone? What shouldn't be going on is officials just trying to blow their whistle to make somebody else happy, instead of just officiating the game. If players are adjusting and coaches are adjusting, you shouldn't just blow your whistle because you're getting a memo that in your last game there weren't enough fouls called."

"It is not an emphasis, not a suggestion, not a, 'Could you think about this?'" national coordinator of officiating JD Collins said. "I walked out of the rules committee last year with a directive: This will change."

Collins, who officiated two Final Fours, worked for 19 years as Division I referee and is in his first year as head of NCAA officials, said he's seeing players learn and react better, that players have already have begun "changing how they're defending."

There are six areas of interest Collins is tracking.

Here are three where officials are doing a good job, according to Collins:

• Defending ball-handlers in face-up situations.

• Not bumping cutters or ball-handlers in north-south/to-the-basket situations.

• Staying true to the offense-initiated contact plays on drive to the basket where the defender is legally holding his ground or verticality.

The three problems?

• Post play is still too rough.

• No-calls on rebound contact are still too prevalent.

• East-west/off-ball cutters are still getting away with too much bumping.

"As I watch games, and I've watched a lot over the past 10 days, I still see on average anywhere from two to four fouls that are not being called," Gavitt said. "In almost every case they're in the low post or are fouls committed off the ball with cutters getting chucked."

Officials, coaches and players alike have been asked to adjust to a 15-year trend of the game in the course of less than one full offseason. Coaches believe they've accomplished this. Collins said college refs "are extremely good at what they do" and estimated -- calling upon past reviews -- that officials hit an "88 to 92 percent" accuracy rate.

"If I were running a business, I would take that every day of the week," Collins said.

The coaches I spoke with have one looming concern, though: consistency with how games are called through conference play and into March. UCLA athletic director Dan Guerrero is the chair of the men’s basketball oversight committee, which was created by the NCAA council last year. He’s in charge of this new group that’s overseeing the sport in a collective ambassador-type of role.

"There is some skepticism that whatever's happened in the nonconference season will revert back to how things were called in the past or how teams have played in the past," Guerrero said. "And then, of course, as you get to the postseason, there’s concern things will change again. We need to see if there’s consistency. One of the things that is of concern is the physicality and whether or not these rule changes have had any positive impact not he physical play in the post."

Some also said the whistle isn't all too different from last year -- so maybe that's why there isn't handwringing over the overhaul. These admission also signal a problem for Collins.

"I think the intent was right, I just think it's going to take some time to get the officials to get them to do it on a consistent basis," Cronin said. "You can't wave a wand overnight."

Other coaches -- such as Painter, Virginia's Tony Bennett, Valparaiso's Bryce Drew and Cal's Cuonzo Martin -- agree.

"I think the officials are charged with a hard job to change things," Bennett said, but added he still wishes more physicality was allowed, especially when defending players who have the ball. "Just like there's a feel for the game for players, there is a feel, whether you acknowledge it or not, for officials. They read situations. You can't let people club each other, but you can't call every little incidental contact."

Martin's coaching philosophy is aggressive play with bumps in the lane but "nothing illegal, nothing malicious." But, in practice, that should no longer be allowed. Martin said his older guys were hesitant earlier this season because of what happened two years ago. His talented freshmen? Foul trouble early and often.

"Before, it seemed like we tried to change the game just for more scoring," Martin said. "The emphasis now, if it's a foul, call a foul."

Drew has the perspective of being a guy who played college basketball less than two decades ago. He still remembers what the game was like.

"I think the offensive players are getting away too much with jumping into guys," Drew said. "As a defender sometimes, what can you do when a guy’s putting his shoulder into you? A couple of the conference games it does look like it’s starting to get more physical, so I'll be interested to see if it does continues."

He does think, along with every coach interviewed for this story, that the transition now compared to two years ago has been much smoother. Perhaps it's in part because players that were sophomores and freshmen then are juniors and seniors now, a la the trouble Cal got into with its younger players. Drew hopes the game moves away from what it became, when it was exponentially more physical with a lot of illegal screens and "the weight room and strength was almost as important as skill."

One coach at a prominent powerhouse isn't too concerned on the consistency issue, though.

"I think it’s been very clear," Arizona's Sean Miller said. "We have some new faces who make decisions on whom will be in the NCAA Tournament on that side of things. That’s the goal for everybody. Players, coaches, teams, as well as officials. As long as that emphasis is there at the top, I think that everybody will continue to do it all the way into March."

Said Cronin: "You've got to embrace change or will hurt you."

In October, as he was watching his team play in scrimmages and exhibitions, Shaka Smart had an epiphany: So many of the teams who won national championships over the past two decades couldn't do so going with the same philosophy forward. When I asked Smart if the new regulations put into place have negatively affected his renowned Havoc defensive scheme he said, "That's still to be determined and would better be determined at the end of conference play."

The fear college coaches have now is turning the game into too much of an NBA wannabe.

"I think we've got a wonderful game and you always have to look at things that make sense to improve it in a little ways," Bennett said. "You need to be smart about your changes. Has the game been majorly or impacted or affected? I was OK with the 30-second clock. We need to be careful that this is not the NBA. I can speak to this because I played in the NBA. College should be different. You can't make it a clone. I'm OK with the changes, I really am, but if we're trying it make this identical to the NBA -- and I think some people are for that, I get it -- but I think that would be a mistake. Because you don't have that talent top to bottom on a team."

On the whole, college hoops is still very much a style all its own, pros and cons included. A big pro that's been an upshot due to the new rules: game time. Of the 36 percent (894) of all games played to that point (2,441) tracked by the NCAA as of Dec. 31 finished in an average of 1 hour and 55 minutes. With roughly the same percentage of games tracked a year ago, games are finishing slightly more than two minutes faster on average.

"That's gotta be good for fans, gotta be," Collins said.

The NCAA's stakeholders are slow to declare victory due to the conference season ahead because of the big reversion in 2013-14. Yet through Tuesday's games -- which amounts to 10 percent of all league play in the power five conferences and the Big East -- scoring is markedly up (73.5 PPG) compared to season-ending data tracing back to 2006-07. From last season alone, it's an 11-percent hike.

"They've been more consistent, so we're actually agreeing with action and not words," Painter said. "Before, when they talked about it, the intent was great. But they're working on changing the system. Our system was broke."

"We need to hold the line on this," Gavitt said on the officiating and coaching. "I don't believe they've adjusted overnight."

The sport is getting better, but if it wants to achieve what it's ultimately aiming for (a bigger return to mainstream appeal from November through February) the most important thing is to remain as critical now as so many where before, when the game hit its aesthetic bottom point and catalyzed all this change to begin with.