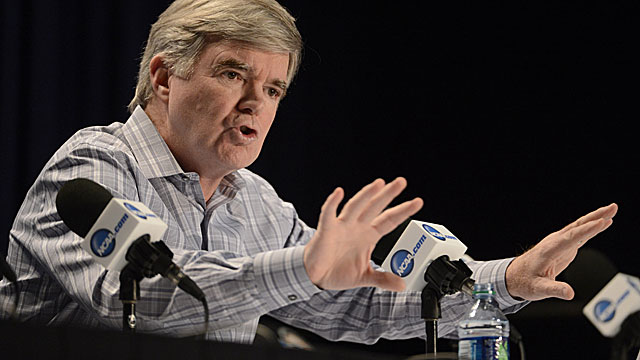

It was a simple question for Mark Emmert.

What’s wrong, I asked the NCAA president in December, if a trust fund was set aside for players? They could access any money earned through sponsorships or marketing rights or whatever after they left school. Heck, even make graduation a condition of getting the money.

"How would you structure a model that basically doesn’t become a recruiting debate?" Emmert countered during a lull at IMG Intercollegiate Athletics Forum in New York.

"It's not hard to imagine if I was recruiting you, I say, ‘I know for a fact you’re going to get a quarter-million dollars worth of signatures [if you come here].'"

Then it becomes a bidding war, Emmert suggested.

Then it hit me ... late, because I didn’t follow up: How would that "trust fund" be any more of a recruiting advantage than the worth of a scholarship at USC vs. one at Troy (Ala.) University?

How would that be different than a coach promising a recruit future NFL riches?

We may be about to find out.

The historic O’Bannon lawsuit took a significant turn on Thursday. A judge basically boiled this epic argument down -- short of a settlement -- to a jury trial starting June 9.

Either way, it seems the NCAA is going to have to change. Arguing its amateurism ideals before a jury -– perhaps one day the Supreme Court -- seems the riskier play.

"The bottom line for the case is that the NCAA and collegiate sports will never be looked at the same today as it was before this case," lead plaintiffs’ attorney Michael Hausfeld told reporters.

"The NCAA has been arguing that limiting college athletes to receiving tuition, fees, room, board and books in exchange for playing is lawful, presumptively," Hausfeld added.

"We're done with that. There's no presumptions. This court is saying if you go to trial, you're going to have to prove it."

I’m sure the NCAA hierarchy has considered it: A jury full of strangers in an Oakland, Calif. courtroom deciding on the future of the NCAA’s amateur model. It is a model that has been in place -- at least philosophically --for more than a century.

The O’Bannon plaintiffs are basically asking for a free market, that players could -- in some fashion -- be paid their market value. Short of that, Hausfeld said his side would be fine with an injunction that would set aside those benefits until perhaps after graduation.

Hello, trust fund. Hello, something very similar to the Olympic model. Our Sochi athletes bathed in glory are allowed to film commercials, make sponsorship money, even earn pay from the USOC for medals. The model isn’t far from what O’Bannon is arguing.

We’re talking about players as a group being able to license and market their likenesses. Hey, anything to get NCAA Football back on the shelves.

Is Olympic figure skater Gracie Gold any less wholesome because she does commercials for United? Does Johnny Manziel become any less exciting if he has autograph money waiting for him once he leaves school?

Explain to me how the competitive balance changes if Manziel faces Rice with or without that autograph check waiting at the end of the college rainbow.

Manziel or McCarron or Winston or Tebow don't become any less savory. Fans that grew up rooting for the Aggies or the Tide or the Noles or the Gators suddenly don’t fall out of love.

The NCAA is defending this case like it’s a home invasion. Let’s face it, the furniture long ago was knocked over.

Pay players? We’re way down that road with the Big Five BCS conferences. They’re about to get voting autonomy in the NCAA governance structure. At the heart of the restructuring is some sort of stipend, cost-of-attendance check for players.

It’s all but a done deal: Athletes are going to be paid from one source or another ... because they’re athletes.

The problem is that the current legal proceeding is moving faster than the NCAA process.

That is, unless, the NCAA governing boards (executive committee/board of directors) get involved and settle this thing. Now. Hey, they’ve spoken on behalf of the membership before. You know, like they did with Penn State.

In the NCAA’s eyes, O’Bannon threatens to become the end of days. It redefines amateurism. But amateurism has been a moving target for the NCAA for most of the last century.

There was a time when there were no scholarships. Ringers were playing. It’s hard to imagine iron-willed Walter Byers digesting the current $550 limit on bowl gifts to players.

Essentially, the NCAA is doggedly defending a model that a) has changed frequently; b) is virtually assured of changing in the future. Most important c) fewer folks seem to mind if it changes.

Those BCS commissioners have openly talked about breaking away because of the current model.

Big Ten commissioner Jim Delany once again waved the Division 4 sword in the air at that IMG forum.

“It’s fascinating to me ... Notre Dame AD Jack Swarbrick told me. "What ought the NCAA be doing?"

Administrators like Swarbrick are concerned about O’Bannon because their athletic departments would have to pay. The vast majority of those administrators struggle to run break-even athletic departments.

But that public debate has been lost. Consider Oregon’s opulence. Then try to argue against schools sharing some of that money in the same of players’ rights.

A December Sports Business Journal report suggested that schools setting aside 25 percent of new TV revenue nationwide would result in every scholarship athlete getting an extra $9,000-$17,000.

In the end, it seems the NCAA is willing to take this case to the Supreme Court to defend an ideal by arguing against five figures. Is $9,000 a year enough for players? Is $17,000 too much?

Twenty-seven months ago a $2,000 stipend was actually approved by the NCAA membership. What happened? The proposal was overridden, then died.

Who, then, is the NCAA speaking for in O’Bannon -- the folks who approved that stipend or the folks who were against it?

That’s a heck of a question to ask with a century-old amateur ideal, a possible trip to the Supreme Court and millions in the membership’s hard-earned legal defense money hanging in the balance.

Here’s the most basic question: What exactly is the NCAA defending?