BIRMINGHAM, Ala. -- To live, the University of Alabama at Birmingham football program first needed to die.

"You hate to say that, but yeah," UAB coach Bill Clark says. "None of this would have happened."

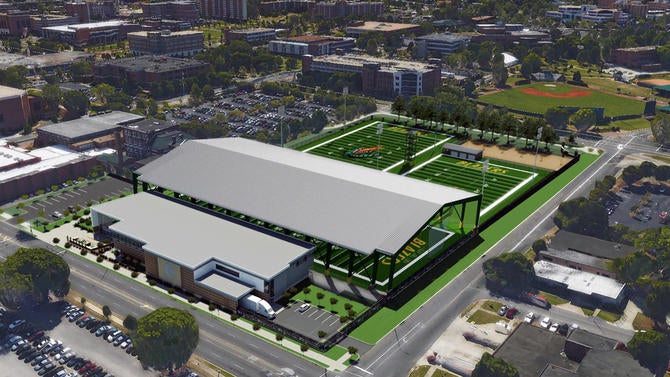

Eliminated for six months before remarkably returning to life, the Blazers, who will return to play in 2017, raised $40 million for football over the past year. They're breaking ground on football facilities estimated to cost $22.5 million, including an indoor field without walls. (More on that unusual idea later.) They signed junior college players like crazy -- 30 from all over America -- as part of a class 247Sports rated No. 2 in Conference USA and 67th in the nation despite not playing football for two seasons.

Meet Second Chance U, where everybody gets a do-over.

UAB 2.0 needed help to get off the ground. Now it's giving players second chances for another shot at major college football. It's quite possibly the most thrilling, inspiring, unifying and frightening experiment college football has ever seen. And yes, Clark has no problem saying he's scared about how this may turn out.

"I laugh when people say this is not scary because it is," Clark says. "It's really scary to me from the social aspect just because they're ambassadors for our school, for me. These guys are coming from all over the country. You're kind of used to having guys who are close to home. You're talking about a melting pot. It's scary in the fact you usually don't have any problems in the season. They just don't have time. Most players get in trouble in the offseason. Now I've got nothing but offseason."

This offseason was gut-wrenching. Former Notre Dame running back Greg Bryant, once a five-star recruit, gave UAB instant credibility by transferring there and convincing other players to do the same. Bryant was shot and killed in May while driving on I-95 in West Palm Beach, Florida. A friend told the Palm Beach Post he thinks Bryant may have been targeted.

"It crushes you," Clark says. "... Greg Bryant was one of those guys who kind of put a stamp on us. He needed us academically, but he came in and it was amazing to me everybody knew Greg Bryant. Everybody's like, 'He's got a 2.75 GPA?' He was kind of our poster child to come in here, get your grades right. He kind of recruited the next guy, who recruited the next guy, who recruited the next guy."

There is no blueprint for UAB. No FBS/Division I football program had shut down since Pacific University in 1995, but Pacific has lived the past two decades without football. UAB ended the sport in December 2014 due to supposed financial concerns. When Birmingham businessmen stepped up with pledges to secure the return, even the NCAA told UAB the association had never seen anything like this.

Clark studied SMU's "death penalty" due to NCAA violations that canceled the school's 1987 season and caused the Mustangs to sit out 1988. SMU returned in 1989 and had one winning record in the next 20 seasons.

"I know they went out there with a bunch of young guys and got killed," Clark says. "To me, you're not gonna run freshmen out there with 20 or 21 year olds. ... I knew we [were] going to struggle recruiting high school kids just by the fact you shut your program down. So we needed to find guys that needed us like we needed them."

To find these players, UAB, a program long steeped in its own irrelevance, has ventured into the forgotten corners of college football's diciest recruiting landscape.

Tapping the juco tank

The euphoria of UAB's return announcement in June 2015 quickly met a stark reality. The Blazers had 12 players on campus. Clark didn't even know how many of them would want to stay until 2017. As the Blazers hold summer camp this month for the first time in two years, 54 of their recruited 60 scholarship players for 2016 are at school. There are close to 105 total players when counting walk-ons, and the plan is to sign about another 25 recruits for the 2017 class.

"What I've learned about junior colleges: Everybody you're waiting for in August is a maybe," Clark says. "It's so hard for these junior college guys to get all the things done because they don't have a lot of help. We talk about them every day. 'OK, what does he have left to do? OK, he's in this lab science now.' You almost become an academician. We're talking more about that than we're talking Xs and Os."

Clifton Garrett, a five-star linebacker who played one season at LSU, signed with UAB out of Arizona Western College. Clark says Garrett won't be at UAB in 2016 due to grades and it's "doubtful" if he will ever enroll.

Fittingly, East Mississippi Community College running back D.J. Law signed with UAB. His academic struggles were highlighted in the Netflix series "Last Chance U" about junior college players trying to get to four-year schools. In 2014, Law bizarrely signed letters of intent to both Ole Miss and Utah and never played at either school. He isn't at UAB yet as he tries to complete his necessary classes and it's not clear if he ever will show up.

This is the life of going all in on jucos. "We want to find young guys and grow them up the UAB way and be our guys," UAB defensive coordinator David Reeves says. "But there was no blueprint to follow."

Clark and his staff became junior college experts. They scoured recruiting services, headlines and the coaching community for tips on players. Since time was all they had, the UAB staff met for hours to discuss players, watch film and try to decide whose story to trust about why a player went to junior college. Behavioral issues and academics tend to be the biggest reasons players go to junior college, though some are there simply to get re-recruited.

Recruiting jucos is so fluid that it became a running joke among UAB assistants of how often they altered travel plans on a moment's notice. Reeves could be recruiting in Memphis and receive a call from Clark to get to Mobile, Alabama, six hours away that same day.

In a twist from how recruiting jucos normally works, Clark told players he wanted their parents involved just like in their first recruiting process.

"Now, they didn't all do it," Clark says. "But we did get a lot of parents that said, 'I've been unattached with them after his grades got down and the hype around him disappeared.' There are a lot of cases where these guys are having to fend for themselves, paying their own way to eat, getting a second job. But the thing I found out is they're appreciative. They've had to go and survive, and so like the [entitlement] of a guy who may have been a four-star or five, that's all been knocked off. Now they're so appreciative to be back."

There's offensive lineman Brandon Hill, who started his career at Alabama and played one season at Mississippi Gulf Coast Community College. Hill told AL.com in February he might "get my master's degree before I even probably play a down" at UAB.

"This is one of the biggest humans you've ever seen and [he] can move," Clark says. "He's a 400-pound guy, and if you get him to 375, he's a first-round draft choice."

There's running back Kalin Heath, an academic qualifier at Kansas State who didn't want to be redshirted there so he went to a junior college to get re-recruited, Clark says. Now Heath, who had between 18 and 20 FBS offers out of high school, could be UAB's starting running back next season.

There's defensive end/outside linebacker Garrett Marino, who originally signed with Arizona State but didn't qualify academically. He went to Montana State and reportedly got dismissed for a violation of team rules and charged with DUI, an account of his time there that Marino denied to AL.com.

"He was kind of one of those wild guys when you first got him," Clark says. "He's turned into this really good academic guy, just a leader. I don't want to say [he] calmed down a lot, but [he] calmed down a lot."

There's linebacker Nick Holman, who transferred from South Florida where he was a reserve. There's offensive lineman Natrell Curtis, who initially signed with Oklahoma and spent two years at Pima Community College in Tuscon, Arizona. There's name after name of juco players who once showed enough promise in the eyes of a four-year school, but struck out the first time around.

"For a guy to go, 'Wow, I get another chance and [can] be part of this comeback,' I sold that and it's real," Clark says. "A lot of them have the same stories. It's scary, but it's pretty cool."

Before UAB shut down, Clark's 2014 recruiting class came from eight different states. In 2016, the Blazers signed players from 13 states plus Washington D.C. and the Ivory Coast. Clark told his assistants to "act like a detective" to find out the real story of why each player went to junior college.

"Almost every one of our guys was academics," Clark says. "I had one social issue; he's not with us anymore. I said, 'Look, we're not taking social problems. We're taking academic problems.' That's worked pretty good for us because we felt like we'd get enough support, and as long as he can do the work, it was just laziness [in the past]."

UAB athletic director Mark Ingram pauses when asked if he has concerns about signing so many jucos.

"It's easy to stand on a glass house and throw a rock, right?" he says. "Everybody's got a story and we've been willing to listen to everybody's story. We've looked at all these guys like everybody else. We don't have any intention of signing any criminals. I mean, you never know what somebody might do. But if we find out anything about somebody -- like if you've got a felony or something like that or a domestic violence situation -- you're not coming here."

One big reason UAB could sign so many jucos is the NCAA won't start counting the Blazers' Academic Progress Rate scores until September 2017, according to Ingram. APR tracks players' progress toward their degree and can result in penalties for a team if it doesn't maintain a minimum score.

If too many UAB players flunk out between now and next September, "it doesn't hurt us from an APR perspective," Ingram says. "It gives us a little more latitude to [sign junior college players] than we would under normal circumstances."

In 2010, UAB needed relief from the NCAA to avoid an APR postseason ban in men's basketball and other penalties in football. At the time, UAB said it was cutting the number of special admission enrollments for athletes because the practice contributed to the APR problems.

Around that time, between 15 percent and 25 percent of UAB freshmen scholarship athletes had admission standards lowered on their behalf each year, compared to 1-2 percent for all freshmen. For example, UAB football's special admission rate, which calculates players who would not have gotten into school without athletics, was 67 percent in 2006-07.

UAB has no existing report that details more recent special admission numbers, according to university spokesman Jim Bakken. UAB requires high school students to complete 17 core courses and have at least a 2.25 grade-point average and minimum ACT score of 20 or SAT score of 1020 (redesigned test)/950 (former test). UAB lists its average academic profile at a 3.6 GPA and a 25 ACT or 1170 SAT.

"We don't have a formalized situation, but our admission folks have been very good working with us as long as people are meeting minimum qualifiers from an NCAA standpoint," Ingram says. "Most of the time that is considered acceptable to get in."

In recent years, UAB football's APR numbers significantly increased. The team graduated 55 percent of its players in the most recent federal graduation report, higher than the rate for all UAB students (50 percent). The football team has access to four full-time staffers and additional tutors, and UAB's top academic support staffer got hired by Texas A&M because of the Blazers' improvement, Clark says.

Still, it's not often an FBS school signs this many jucos at once. Clark admits he "no doubt" worries about players flunking out or committing academic fraud. He says he stresses to them to never cheat, sit in the front row at classes, take off their hat, and communicate with professors.

"That goes back to the worry," Clark says. "You do all this work for a guy and he could flunk out mid-term and not be here next year."

UAB's indoor practice field without walls

If there's a symbol of Second Chance U's grand experiment of rebirth, it's the indoor practice field that will soon be built with no walls. No, seriously. There are no walls.

UAB is calling it a pavilion, as in the Legacy Pavilion. Legacy, a credit union that opened in 1955 to serve the UAB community, signed up for a 20-year, $4.2 million naming rights agreement. Ingram says it's the second-largest naming rights agreement in the history of the University of Alabama System, which includes UAB.

And yes, Ingram knows how an indoor field with no walls sounds.

"It's just like throwing the ball on fourth and short," says Ingram, who used to work at Temple and Tennessee. "It's brilliant if it works, but if not, you're an idiot."

Ingram always wondered whether a pavilion could work for a football team far enough in the South. If it's raining, the field is dry. If it's hot, there's shade. If there's lightning, there's safety. So why add walls and the extra costs? But just to make sure he wasn't being ridiculous, Ingram floated the idea to a friend who's an architect.

UAB will pay $4.7 million for the pavilion instead of $15 million for a true indoor facility, according to Ingram. Since there are no walls to build, UAB will enjoy significant savings without windows, doors, air conditioning, fire and sprinkler system, and much more lighting.

"And we're getting what we want," Ingram says. "We don't think anybody else has this. I've had other ADs call and say, 'That's awesome, we love it.' It doesn't get that cold in the winter here. If we need to, can we put on a long-sleeve T-shirt? Is it really that hard?"

For an estimated $22.5 million, UAB is buying a new football building, the practice pavilion, a 100-yard outdoor field and an 80-yard outdoor field sandwiched right next to a planned sand volleyball pit. Most of the money has been raised, though fundraising continues. Construction starts this month.

The $22.5 million figure represents the approved budget from the University of Alabama System Board of Trustees, which oversees UAB. The fact that Alabama's board approved that much money for UAB football would have been unimaginable not long ago. Paul Bryant Jr., the son of legendary Alabama coach Bear Bryant, is no longer on the board and was often viewed as a major obstacle to try to build up UAB football as the fan base dwindled.

"It was hard to believe you were hearing these things from the board less than a year and a half after they justified the closure of UAB football," says Alabama state Rep. Jack Williams, a UAB supporter who helped lead the program's revival. "There seems to now be a real desire to work cooperatively, and I honestly can't point to a board member who doesn't seem to really be on board with this."

UAB brought football back partly because of how embarrassing the shutdown looked as contradictory information leaked out about how long it was in the works and dollar figures didn't add up. The most important factor, though, was local businessmen who stepped up financially. In a city filled with Alabama and Auburn fans, UAB is now trying to sell that its university as a whole is vital to Birmingham, football is important to UAB, and thus they're all intertwined.

"Some of our local community leaders look at Louisville and how the city has grown and benefitted from the University of Louisville's success," Ingram says. "They made a commitment with facilities like we are and look at what they are in terms of athletic success today compared to 20 years ago. It's a dramatic turnaround. I know 20 years sounds like a long time, but it's really not."

Williams thinks UAB, a founding member of Conference USA, could one day be attractive to a conference like the American Athletic Conference, or it could join a new league with geographical neighbors from the South. UAB's $30 million athletic department budget now includes about $600,000 less per year from C-USA TV revenue due to a downtick in the league's value after losing upper-tier members.

"In the next four to five years, you'll probably see UAB looking at greater options," Williams says. "You've got schools in Charlotte, Atlanta, Memphis, Tampa, Orlando, Birmingham. There's the makings of pulling something together that could be significant in the South, which Conference USA was at the time it started."

Ingram says moving to another conference is not part of UAB's plan. "If at some point all the conferences realign, then being competitive and showing a willingness to want to be competitive, that will help us," he says. "But that's not a driver in our decision-making."

One of the most fascinating parts of UAB 2.0 is how deeply connected it is with Clark, who knows all about fundraising from his days as a successful Alabama high school coach. Clark punctuates most of his posts on Twitter with #theReturn. It resonates with fans because, just like them, Clark got blindsided by football's cancellation after his first season.

Other schools with jobs have called Clark, who replies "maybe" when asked if he could have gotten the Southern Miss job in January. There is no given how long Clark will stay at UAB or what #theReturn would look like if that day ever comes. Clark's role in this reboot isn't lost on him.

"I guess every day people are stopping me: 'Thanks for staying. Thanks for being here. We needed this,'" he says. "That's when maybe on these roller coaster days you say, 'OK, that's why we're here.'"

Clark would not have agreed to a five-year contract extension last fall if UAB had not created a non-profit foundation to directly benefit football. UAB grad Jack Crowe, a former coach at Arkansas, Clemson, Auburn and Jacksonville State, helped launch the foundation, which is patterned after other privately funded organizations that help subsidize athletic departments.

"It's creating an organization like Clemson did with IPTAY," Clark says. "Where was Clemson 40 years ago? They were right where we are. So they had to start somewhere."

When UAB football returned last June, Clark told supporters to quit talking about their desire for an on-campus stadium. The Blazers play at decaying Legion Field that eventually needs an end-game solution. UAB unsuccessfully tried in 2011 to create a political consensus to build its own $75 million stadium, only to see the Alabama board shoot down the plan without public discussion by citing a lack of fan and financial support.

The city of Birmingham, which once had unrealistic dreams of building a 70,000-seat dome, is now talking about a 45,000-seat open-air stadium. After years of staying silent on the project, UAB (the largest employer in Alabama) publicly supports the stadium and would be a tenant if it gets built.

"The stadium talk was so divisive," Clark says. "We needed to have other things first."

The blueprints of UAB's new building sit on a table in Clark's office. They've been there for two years so Clark can sell recruits a vision he didn't even know would play out. On a wall there's a picture of former UAB coach Watson Brown's blueprint of his building idea from more than a decade ago. Clark found it when he first took the UAB job and put it on a wall. His wife recently told him it's time to take the picture down.

"I'm not taking it down until I put the new building up," Clark says.

Staying focused without games

It's a Friday morning in mid-July and Reeves, UAB's defensive coordinator, meets with some staffers inside the Blazers' tiny football building, which resembles a dentist's office. Next door, there's a bird flying around in the same locker room where hearts got crushed and lives changed in 2014 when UAB president Ray Watts told his players football had to be shut down because "you don't know what you don't know." Watts got his own do-over. He's still president despite a no-confidence vote by UAB's faculty senate after football was ended.

On this day in July, Reeves is analyzing the Blazers' defensive tendencies. They haven't played a game since Nov. 29, 2014, and they won't play one for 14 more months. No matter. Reeves, a self-described workaholic, estimates he's putting in 60 hours a week this summer while admitting there's a danger of overanalyzing with this much time off.

"You absolutely can," Reeves says, laughing, "and I've got a group of guys in there that remind me of that."

August brings UAB's first fall camp since the program got shut down. There will be practices this fall. There will be dress rehearsals for games, right down to eating a team pre-game meal and walking the field at Legion Field.

Still, how do coaches and players stay focused and intense for one more year with no games? It's a question Reeves constantly asks himself. UAB is going to get thrown right back into C-USA and major college football in 2017 without a grace period normally reserved for transitioning into the FBS. Waiting until January to flip the switch won't cut it.

"It's not hard for me to find motivation because I was in that meeting when they took football away," Reeves says. "You tell your players all the time, 'You better play like it's your last deal because you never know when it's gonna be gone.' You know what? We lived that. We've still got some coaches and guys here who lived it."

Indeed, it was a deeply raw and emotional day when Watts officially informed the team that the program would be shutting down back in 2014. The following video went viral.

Time is healing many wounds at UAB. One sore point remains: All of those former players whose lives were turned upside down when UAB football suddenly ceased to exist. Yes, some players moved on to even better opportunities, such as linebacker Jake Ganus at Georgia and running back Jordan Howard at Indiana. But so many didn't.

"That's when it's hard not to get upset when you think about that average guy," Clark says.

Ja'Won Arrington was that average guy. He spent 2012 at Alabama A&M before transferring to UAB as a walk-on. Clark awarded Arrington a scholarship and he played 11 games his junior year of 2014 as a reserve running back and special teams contributor.

After UAB's program shut down, Arrington transferred to the University of North Dakota. It was too cold, too far from home, and too different than the family he had made at UAB.

Shutting down UAB football "impacted me emotionally," Arrington says. "The thing is you put that trust in there and you say this is where you want to spend four to five years of your life and be a part of a program, and all of a sudden it's gone. That trust that's there, it's hard to get that trust back. So many people's belief was there."

Arrington is back living with his grandparents in Birmingham and still hasn't given up on UAB. He got accepted into graduate school in engineering but won't be able to play again. The 2016 season would have been his sixth year of eligibility. Since UAB isn't playing, Arrington basically petitioned the NCAA for a seventh year that, he says he was told, has never before been granted.

"I'm frustrated," Arrington says. "I didn't want to play anywhere else but UAB."

Arrington has talked about possibly becoming a graduate assistant if a spot becomes available. "Terrific kid," Clark says. "He knows how to do things."

The NCAA will be answering long-term eligibility questions for many UAB players at various points in their career. In order for UAB to recruit jucos, the NCAA is allowing the school to apply for individual waivers of an extension on their eligibility clock. Otherwise, jucos likely wouldn't have signed in 2016 knowing they would lose a year of eligibility.

The NCAA will rule on waivers over a period of time on a case-by-case basis. As long as players are in good academic standing, Ingram says he expects favorable responses from the NCAA.

"It would be unfortunate for any of them to not get that and lose time, and quite candidly, it would really hurt our program," Ingram says.

Because C-USA wanted UAB back without a transition period, the NCAA waived a rule requiring FBS teams to have at least 90 percent of their 85 scholarships awarded on a rolling two-year average. UAB signed 37 players in 2016, causing at least one C-USA school to express concern that the NCAA is allowing UAB to oversign and receive recruiting advantages.

"I mean, we over-signed by five -- five -- one time in one class," Ingram says. "We were given eight additional official visits last year. We had to sign a double class. We didn't get double the number of official visits. Some of it is sour grapes. Some of it is lack of understanding. The majority of ADs in our conference that I've had this conversation with say, 'Look, our conference is better if we're all better. A pitiful UAB team is not good for anybody. So we beat a team that's horrible? What does that mean?'"

Clark sold playing time to recruits -- when you have no players, it's pretty easy -- and time off from playing. Players with questionable academics can have more time to adapt to school. Injured players can have more time to heal.

Health is one reason quarterback Tyler Johnston, Mr. Football in the state of Alabama last year, signed with UAB. He went 35-0 in his career at Spanish Fort High School but injured his elbow in the state semifinals. Navy, Army, Southern Miss, South Alabama and Louisiana-Lafayette offered scholarships as a quarterback. Ole Miss showed interest at safety or linebacker. Johnston had Tommy John surgery the week he signed with UAB last February.

"I have a throwing program now and it doesn't rush me and my program," Johnston says. "If we had a season, I'd be trying to play. This whole year is going to help out a lot."

Clark doesn't know if his future quarterback is on campus yet. Johnston was considered a big signing for UAB. A.J. Erdley arrived on campus after losing the quarterback job at Middle Tennessee and then transferring to Mississippi Gulf Coast Community College. Some walk-ons are on campus. More quarterbacks may be coming.

"It's everything to get a quarterback," Clark says. "It's not overstated that you go as that guy goes."

Starting Sept. 2, 2017, UAB will become its own guinea pig to a fascinating question: How competitive can a team be in major college football after essentially giving itself a two-year death penalty? The Blazers will have a full C-USA schedule and nonconference games against Alabama A&M, Ball State, Coastal Carolina and Florida.

"We've got talent," says UAB wide receiver Collin Lisa, who returned to the Blazers after contributing at Buffalo. "We're not coming out there looking just to compete. We want to go to a bowl game that first year. That would be huge because we were eligible in 2014. To come back and do that, you couldn't write a better script for a movie."

Hollywood might not believe the script if that happens. Reeves, the Blazers' defensive coordinator, jokes that he hopes a movie gets made before he dies so he can say what really happened with the shutdown.

"They need to find a good actor to get ready to play me," he says. "I'm kind of a Kevin Costner guy."

Clark shrugs his shoulders when asked how competitive he thinks the Blazers can be in 2017. He's a positive person by nature so he wants to think the glass is half full. He's also realistic of how hard it will be to get so many of his players to 2017, whether it's due to academics, their inability to adapt socially or their desire to graduate and move on in life.

"All of those things worry you," Clark says. "There's just a lot of unknowns."

To live, UAB football first had to die.

To survive and possibly thrive, Second Chance U must navigate the joys and risks associated with the biggest do-over in college football history.