I still like to score games on occasion. It’s a baseball liturgy of the first order, and there’s a certain Zen that goes along with taking part in that peculiar shorthand, especially when attending a game in person. The reality, though, is that these days we have all manner of mobile trackers at our disposal -- our own GameTracker, for instance -- that do the work for you, right down to the pitch-by-pitch level. The tactile pleasures and deep engagement that come with traditional pencil-and-paper scoring mean that practice will always have a place, but in the here and now it’s no longer driven by necessity.

It’s too much to say your paper scoresheets and scorecards are lost to obsolescence, but in case you find yourself pining for a new way to use them -- admittedly, you’re probably not -- then stick with me for a few.

I got this idea initially from helping coach my son, who’s a youth baseball player. Like any other quasi- or actual coach, I find myself uttering vapid cues that probably do nothing to benefit the player. “Keep your head on the ball,” “shoulder to the mitt” and all that stuff. Once when he was hitting in the cage, I spit out, “Beat the ball!” which is almost impressively inane and useless. I meant “beat” as in “reach point A before the pitch does,” not “assault the ball.” Although I suppose I meant that, too.

Doubtless this did nothing to advance any baseball skills, but it got me thinking about that foundational bat-versus-ball rivalry -- the one that’s played on all 300 or so pitches in every major-league game. I also thought about how, during spring training, more and more teams are supplying their hitters not with traditional spring training stats but rather figures on how often they’re squaring up on the ball, even if said squaring up results in an out. The flipside applies to pitchers, of course.

Those things plus idle hands led me to an alternative game-scoring method I’ll call “Bat vs. Ball.” It’s premised on the idea that every single pitch is in essence the bat in the hitter’s hands against the ball propelled from the pitcher’s hand. While all those freely available trackers noted above are in essence scoring the game for you in the traditional way, you decide who wins each pitch, the bat or the ball. Concoct your own symbols if you like, but I use a verticl line (I) to indicate the bat won a pitch and a circle (o) to indicate the ball won. Much of the determinants are self-evident, but some require judgment calls ...

- A called or swinging strike: o

- A ball or hit batsman: I

- A well-struck hit: I

- A weakly hit foul ball for strike one or two: o

- A foul ball with two strikes that keeps the hitter alive: I

- A batted ball that’s a routine out (including fielder’s choice): o

- A batted ball that results in an error: o

- A batted ball that should’ve resulted in an out but isn’t scored an error (e.g., a pop-up that drops between fielders): o

- Sac bunts and sac flies? They’re outs, so ... :o

- Feel free to ignore the 40 or so instances of catcher’s interference that happen each year.

Those are simple enough and require nothing more than your attention on the game. However, other instances will ask you to make evaluations when it comes to quality of contact ...

- Was it a dink hit or slow-roller that died in the infield grass for a single? Maybe it’s: o.

- Did the hitter lay into one and line out, get victimized by a great snare at third base or by a rangy center fielder going into the gap? Maybe it’s: I.

- Back to foul balls. What if the hitter absolutely cracks a hanger or middle-middle fastball down the line, but it’s just outside the foul pole for strike one or two? Maybe it’s: I.

- These instincts of yours will be challenged by things like humpback liners, grounders scalded right into an infield overshift, and maybe even a deep drive that dies on the track in a crosswind. Those can go either way. It’s those kinds of plays that mean two different Bat vs. Ball scorecards from the same game may not wind up with the same “final score.” In that way, it’s like being a boxing judge -- science leavened by art.

What I like about this relative to the traditional box score/scorecard is that it captures more of the batter-versus-pitcher spectrum, albeit in far less detail. Some hits have little to do with the merits of the hitter, just as some outs occur in spite of the pitcher’s work. The thing to get away from is pure outcome-based judgment calls For instance, the final pitch of this at-bat ...

... Would be a “o” in my book since it was a cutter up and in enough to miss the barrel and induce a tepid pop-up that barely reached the outfield grass. Like I said, judgment call.

Batters and pitchers joust with each other to control the strike zone -- taking pitches that don’t look good out of the hand, attacking the corners, sneaking a breaking ball over when the hitter’s looking fastball, that sort of thing. But they also battle over how authoritatively the bat will meet the ball. Hitters want to put the sweet spot on it, and pitchers, by upsetting timing, mixing up speeds and levels, and incorporating late movement, seek to avoid same. Some hitters are very good at doing damage on contact, just as some pitchers are good at missing barrels. This system, in very broad and simple terms, captures both that initial battle over the strike zone and then the post-contact battle that brings in all those external considerations.

Also -- circling back to the matter of human spawn and raising to appreciate This, Our Baseball -- I find the simplicity of this system is a great way to introduce kids to the rhythms and attention demands of scoring a game but while doing so in a format that’s less inscrutable than the traditional method. It’s also easy for kids to wrap their wee heads around that one beautifully basic question that starts the whole process: Who won that pitch?

After the game is over, it also provides with another layer of considerations. Did a pitcher manage to “win” the vast majority of his pitches despite getting some crooked numbers hung on him? Did an otherwise forgettable hitter manage to win all his at-bats against the opposing ace? Of those 116 pitches he threw in that complete-game shutout, how many did he “win”? How many did your friend sitting next to you doing the same thing think the pitcher won? Does this particular Bat vs. Ball scorecard accurately predict the final box score? If not, why not? Typically, we look at strikes as a percentage of total pitches as a stand-in for command and control. But what changes when a pitcher throws a lot of strikes, but loses a lot of Bat vs. Ball encounters? That sort of thing.

By way of example, let’s go through the classic, nine-pitch struggle between Reggie Jackson of the Yankees and Bob Welch of the Dodgers in Game 2 of the 1978 World Series. The Dodgers are up 4-3 with two outs and two on in the ninth, and one of the best power hitters in baseball is facing a 21-year-old rookie with a 95-mph fastball ...

And now Bat vs. Ball ...

- o - Mighty whiff by Reggie.

- I - Ball one, up and in.

- o - Foul back, strike two.

- I - Solid foul with two strikes.

- I - Solid foul with two strikes.

- I - Ball two, up and in.

- I - Solid foul with two strikes.

- I - Ball three, high.

- o - Mighty whiff by Reggie.

Despite the final outcome, Jackson won more individual pitches. This makes sense, in that there’s value in the running up the pitch count of the guy on the mound and in that the hitter’s more likely to succeed the longer the plate appearance goes. Last season, for instance, hitters had a robust OBP of .455 after getting to a full count, and league-wide there’s only one intentional walk baked into that figure. That’s why I think it’s appropriate for hitters to be rewarded for extending the bat. Also bear in mind that the pitcher can win no more than three pitches in an at-bat, while the batter is theoretically unlimited thanks to the possibility of foul ball after foul ball. That said, keep in mind that batters in the main typically average not quite 4.0 pitches seen per plate appearance, so deep AB’s like Reggie’s above are relatively rare.

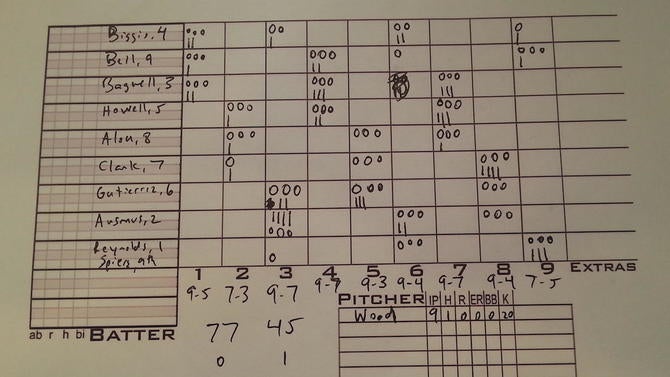

Finally, let’s see those whole thing in execution. To do this, I’ll apply our method to Kerry Wood’s legendary gem against the Astros on May 6, 1998. You know, the 20-strikeout dominance seminar. Here’s the full game ...

And here’s my Bat vs. Ball scoring of Wood’s outing ...

Yes, I use a pen, and, yes, my penmanship is trash driving on the rims. Wood was obviously dominant, but he really benefitted from a liberal outside corner of the called zone, especially with his breaking stuff. Qualifiers aside, though, he won a lot of pitchers. Of his 122 pitches on the day, he won 77 of them (63.1 percent). For what it’s worth, I ruled the lone hit of the day -- Ricky Gutierrez’s grounder that Kevin Orie sort of misplayed -- as an “o” in Wood’s favor. The 20-year-old rookie fireballer won every inning, and just two batters -- Brad Ausmus in the second and Dave Clark in the eighth -- won more pitches than Wood in an at-bat.

So that’s what a gem of gems looks like, but what about when a pitcher soils the linens out there on the mound? On Wednesday night, Rangers closer Sam Dyson blew the save and in doing so allowed five runs -- including a grand slam to Francisco Lindor -- while recording only one out. I went back through and scored it, and I have ruled, while wearing a magistrate’s wig, that Dyson won just seven of 21 pitches (I even judged Tyler Naquin’s chop-single in the pitcher’s favor), which is a “pitch winning percentage” of just 33.3. That’s not optimal from the moundsman’s standpoint.

But what’s the baseline? Consider this a quick-and-dirty method, but I of the more than 700,000 pitches thrown the majors last season, roughly 54 percent went in the pitcher’s favor. This doesn’t account for lucky dink hits that would be scored o’s or stellar defensive turns that would be ruled I’s (I was eyeballing data, not 700,000 actual pitches, of course). But it’s a rough guide for what an average figure should look like.

This approach is at its best when balls are in play, and that obviously wasn’t the case to much of an extent during the Kerry Wood game. Thankfully, MLB and commissioner Rob Manfred have signaled that they’re acutely aware of MLB’s current strikeout problem -- the defense simply isn’t involved enough these days -- and are exploring structural approaches to bring contact back to the game. If that comes to pass, then Bat vs. Ball may have a bit more appeal. That, after all, is where your subjective judgment skills come into play, and that’s where you can have some fun and healthy debate with this.

Hey, man, I’m just spitballing over here. Win the pitch, people. Win the pitch.