The realization for Allen Greene came during an SEC athletic directors' Zoom call four days after George Floyd's death last May. To open the SEC spring meetings commissioner Greg Sankey mentioned the tragedy that changed the country.

"That caught me off guard, in a very good way," said Greene, Auburn's athletic director. "The commissioner of the SEC had the wherewithal to bring up an issue with ADs given the weight of what is going on in our worlds.

"That told me that these riots caught the attention of mainstream America."

That was one observer's view of an ongoing social revolution. Greene is a Black, 43-year-old native of Seattle who played baseball at Notre Dame and in the minor leagues. Auburn's AD since 2018, Greene was named this month by the NCAA as a Champion of Diversity and Inclusion.

Like a lot of his peers, he finds himself enlivened, a part of that social revolution. Floyd's death inspired him last year to help start the Division I Black AD Alliance. It is co-chaired by Kansas City AD Brandon Martin and includes a 16-member executive committee. All that came at about the same time Maryland coach Mike Locksley started the National Coalition of Minority Football Coaches.

If you haven't heard from them, you will. Only about 15% of Division I ADs are Black. Only 11 of the current 130 FBS coaches are Black (8.4%), down from a high of 19 in the 2011 season. Meanwhile, about half of Division I FBS football players are African-American. That figure is at 61% in the SEC, the conference that has won 11 of the last 15 national championships.

For the first time since 2015 no Power Five school hired an African-American head football coach this year. Only one (Charlie Huff at Marshall) of 15 FBS coaches hired in the most recent cycle was Black (Boise State coach Andy Avalos is Latino.)

"Well, the industry has spoken," one minority AD texted to CBS Sports when Gus Malzahn -- who is white -- was hired Monday at UCF.

FBS schools received a C- grade for overall racial hiring practices in 2020, according to Richard Lapchick, whose assessments are widely respected as director of UCF's Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sports. Those same schools received an F for gender hiring practices.

Five days before the Floyd tragedy last May, Vanderbilt's Candice Storey Lee became the SEC's first female AD. She is only the fifth female AD currently at a Power Five school.

As a whole, ADs are usually somewhat conservative and corporate. That stance has changed for some with society's ills mounting in these unique times. COVID-19 meshed with the Black Lives Matter movement and social awareness have made it so.

"When George Floyd died … I remember thinking to myself, 'This is just another Black man dying at the hands of the police unnecessarily,'" Greene told CBS Sports. "So it didn't strike me as odd. … I have unfortunately become numb to those occurrences. What sparked it was those SEC AD meetings."

Maybe social awareness would have been renewed without the upheaval of last year. Whatever happened, the nation's turbulence sparked a movement. Athletes, administrators, the afflicted, all of them have been more inclined to tell their stories.

"The talk in a white family household is the birds and the bees," Greene said. "The talk in a Black household is how you're supposed to behave when you engage with law enforcement. It pains me to have to tell you I just took my daughter to the DMV to get her driver's permit. For me to have to have a conversation with my daughter about how to stay alive as she begins to drive, that tells you something is wrong."

Greene referred to colleagues in a certain part of the country who have to plan ahead when they go to the beach with their families.

"My wife and I get a full tank of gas before we leave," one AD said. "We get all the food, all the snacks, all the water. We get everything ready so we don't need to stop because I don't feel comfortable stopping [because of the possibility of racial prejudice]. The beauty of white privilege is you don't even have to think about that."

Relating to that, Michigan AD Warde Manuel said, "In the South, you know who doesn't like you. In the North, it's a little bit more hidden. People don't tend to voice their displeasure. They don't have Confederate flags on the back of their cars."

Manuel is on the executive committee of the Alliance. The 52-year old former lineman for Bo Schembechler grew up in New Orleans but remembers a trip to a mall in nearby Metairie, Louisiana. Today, he commands one of the largest, richest athletic departments in the country. As an 8-year-old child, Manuel remembered watching the Ku Klux Klan asking locals for donations.

"My mother basically told me, 'You're going to have to learn to deal with racism in this town and in this country,'" Manuel said. "You can't run from it. You have to keep moving forward.' For me, man, I've never forgotten that experience."

The outside world doesn't necessarily know about Manuel's study of the civil rights movement that included reading the works of Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr. and John F. Kennedy. Like Greene, Manuel was disturbed by those police shootings.

"It's not easy being a police officer," he said. "But they have to start standing up and saying that's not acceptable policing."

Manuel has had the same talk with his son as Greene did with his daughter. Evan Manuel grew up with uncles who were police but, his father said, "I've told him how to manage himself when he gets pulled over -- hands on the steering wheel, where they can see."

It's that duplicity that endures. Minority athletes complain they're heroes on Saturday, but during the week when they walk the campus as students they are seen in a different light.

"It happened at a very young age," said Northern Illinois AD Sean Frazier, a former Alabama football walk-on, "the perception because I was talented [athletically] I didn't have to work hard. … I always felt like I have to be better than good [outside of sports]. I can't be just OK."

Manuel added: "Student-athletes feel when they take their uniforms off they're the same people who had been senselessly killing when they're on video. I'm in the car with a baseball cap on. I've got a sweatshirt on right now. They don't know who I am and what I do.

"But when I step to the podium and I get introduced as the Donald R. Shepherd director of athletics at Michigan, those people who may have treated me poorly with a cap and sweatshirt on are all the sudden applauding."

Frazier played for three Alabama coaches. Coming from Queens, New York, he was recruited by the likes of Temple and Syracuse but the attraction of playing for Alabama was too strong. His mother had attended Tuskegee University, a historically black college in Alabama.

"My most shocking moment: There was a Black fraternity row at Alabama," Frazier said. "I found that it was very odd. All the other fraternities were in another location. I don't know if it was segregation [but] people knew their role down in the South. We're talking 1987-91. There was a different fraternity designation for Black and white."

Kevin Warren was the first African-American COO in NFL history (Minnesota Vikings) when he was hired as the Big Ten's first Black commissioner in 2019. Diversity immediately became a main initiative. In June, Warren wrote an open letter saying "George Floyd's death cannot be in vain."

"This was no longer someone else's issue to address," Warren said.

His brother, Morrison, was the first recruited black football player in Stanford history. His dad fought in World War II and witnessed Nazi atrocities. Warren's grandmother is from Mexico.

In the middle of 2020s, disruption civil rights leader Rep. John Lewis died. Lewis became the first Black lawmaker to lie in state at the U.S. Capital.

"It brought full circle a lot of things my parents talked about a civil rights movement," Warren said. "This is not a white issue or a Black issue. This is a people issue. We live in the greatest country on Earth. We need to keep that way. We gotta stop being divisive."

Black Lives Matter didn't start with Floyd's death. It emerged out of Ferguson, Missouri, protests following Michael Brown's killing in 2014. Missouri players told CBS Sports at the time they took their inspiration to threaten a boycott over perceived racial injustice on campus from Ferguson.

Since last summer, companies in almost all sectors have been impacted by a social awakening. The latest might be the Jacksonville Jaguars who last week signed off Urban Meyer's hiring of strength coach Chris Doyle. Doyle has been accused of making racist comments at Iowa before a mutual separation from the school last year. He resigned from the Jags last Friday.

Last month, Lead1 Association presented its recommendations intended to create more opportunities for people of color. Lead1 is the professional organization representing FBS athletic directors.

The report recommended the NCAA, College Football Playoff and FBS conferences take "greater responsibility" in hiring practices. That initiative included financial incentives for diversity hiring as well as a "scorecard" tracking search firms' minority success rate. The Knight Commission recently recommended the CFP set aside 2% of its annual revenue to boost diversity hiring.

The NCAA is blocked from adopting a Rooney Rule similar to the NFL because of state and federal laws. The Rooney Rule requires NFL teams to interview at least one minority candidate or be subject to a fine. However, the West Coast Conference did recently adopt the "Russell Rule" on its own that requires minority candidates for senior athletic positions.

Frazier -- a leading voice among Group of Five ADs -- co-chaired the working group that came up with that white paper. Two of the 10 FBS commissioners are now Black. The Sun Belt Conference hired Keith Gill as its commissioner out of the Atlantic 10 in 2019.

Clearly these AD jobs have become more than fund-raising and balancing budgets. There is a higher calling in these stressful times. Warren went so far as to start a Big Ten voter registration initiative last year. He pushed back against any assertion he was trying to use his office for political purposes.

"I personally believe that when people don't have an answer, they make it political," Warren said. "That's almost like the trap door. If I don't have an answer, or I really don't want to work through the issue then let's make it political."

There is nothing political about Earl Edwards' background. The 70-year-old AD at California-San Diego (UCSD) was born in Selma, Alabama. His parents grew up sharecroppers in the Deep South. The family eventually settled near New York City and would make the annual 18-hour car trip each summer back down South to see family.

It was during that time Edwards would literally the country change through the window of a car. His family would go from states that were tolerant of minorities to those that weren't.

There were separate drinking fountains. Edwards' family was turned away in a restaurant.

"Suddenly, music and noise and as soon as we walked in there was absolute silence," Edwards said. "That still sticks in my head. The waitress says we can't eat there, if we want some food we have to go to the back. We ended up just leaving.

"It really forced me to focus on the positives of life in general."

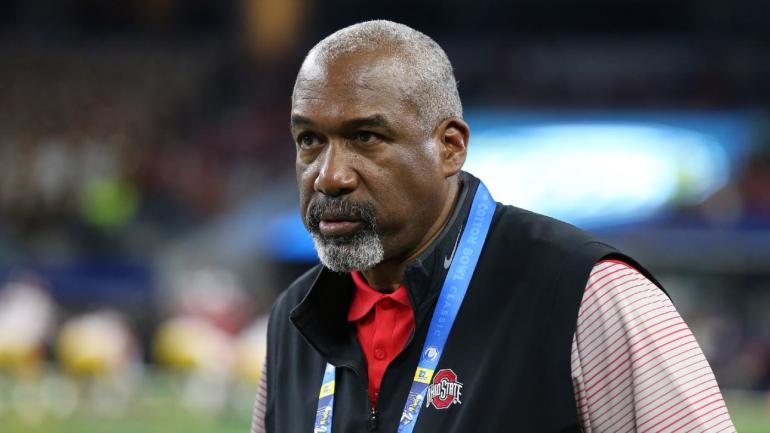

Gene Smith is one of the most powerful persons in college athletics. Ohio State's 64-year-old AD has been mentioned as a conference commissioner, even a minister of all college sports if there was ever such a thing.

"My goal, frankly, was to be an electrician," Smith said. "My dad was an electrician."

Instead, he became the first member of his family to graduate from college at Notre Dame in 1977. Smith was a defensive end on the Irish's 1973 national championship team.

After establishing himself as Eastern Michigan's AD from 1986-13, Iowa State called out of the blue.

"I did nine interviews before I got the Iowa State job," Smith said. "I was a token in many of those interviews."

After six years at Arizona State (2000-05), Smith was one of the top administrators in the country. Ohio State called in 2005. Smith was the guiding force during both a turbulent and exciting time at Ohio State. He fired Jim Tressel, hired Meyer and has overseen Ohio State's greatest football run since the Woody Hayes era.

For Smith, last summer's racial unrest "was painful. I grew up in the '60s in Cleveland. We had the Hough riots. It brought back those memories.

"It matters who you hire in a police force. … People with a certain attitude are in that profession. You have ongoing incidents of behavior that demonstrate they shouldn't be there."

At one time Martin, the Kansas City AD, was the next big thing. He had become one of the top lieutenants at both USC (under Mike Garrett) and Oklahoma (under Joe Castiglione). Finishing as a runner-up for the Houston job in 2009, Martin got his first AD job at Cal State-Northridge in 2013.

In 2018, he was fired on the same day as his basketball coach, former NBA star Reggie Theus. Less than a day before the pair reportedly had a physical altercation.

"Things went south between Reggie and I," said Martin, who added that if he had gotten the Houston job, "I'd be at a Power Five school now. That changed the trajectory of my career."

Instead he is 2 ½ years into a career as AD at a mid-major whose basketball program hasn't been to the NCAA Tournament since moving to Division I in 1987.

College athletics needs Brandon Martin, too. He remains inspired about origins about growing up in South Central Los Angeles. A cousin shielded him from joining a gang.

"I was the chosen one that was going to be able to get out," Martin said.

His father, Earl, drove a delivery truck for the Los Angeles Times. Martin went on to play basketball for George Raveling at USC and played professionally in Europe, South America and Asia while getting his master's and Ph.D in education.

There were interviews where Martin thought he was that token Smith had referred to. But as one of that 15% of Black Division I ADs, Martin wants to make life better for everyone.

"I've been trained at the highest level," he said. "I'm in the position I am because of me competing against me, wanting to lead my own [department]."

With the Alliance, he is leading more than Kansas City.