SAN FRANCISCO -- It's not easy to get a crowd of 150 kids under control -- if you've ever tried, you know it's pretty much an exercise in futility. These kids are particularly frenzied on this day, around 4:30 p.m. in the pristine gym of the Don Fisher Clubhouse, a branch of the Boys and Girls Clubs of San Francisco. They're packed into the far right side of the bleachers, each donning a red shirt with the words "Go Big" written broadly across the chest. The annoyingly infectious rhythm of "Despacito" pounds from the DJ booth set up in the opposite corner of the gym, while the kids entertain each other with their own unique renditions of whips, nae-naes, dabs and whatever other dance moves we're too old to be familiar with.

Then, silence.

The DJ grabs the mic, and the kids know what that means. The moment they've patiently been waiting for has finally arrived.

"ALRIGHT, ARE YOU READY?" the DJ shouts. "MAKE SOME NOISE FOR ANDRE IGUODAAAAALAAAAA!"

"It's big," said Harold Love, senior area director of the Boys and Girls Clubs of San Francisco. "We've got a lot of kids that don't get an opportunity to see someone famous."

While Warriors forward Andre Iguodala's face might not be plastered on national TV like LeBron James or his teammate Stephen Curry, he's instantly recognizable to the kids in this audience. These are hardcore Golden State Warrior fans, and they know the 2015 NBA Finals MVP when they see him.

Iguodala has no trouble relating to these kids. He used to be one of these kids. Growing up in Springfield, Illinois, after every school day from third to seventh grade he made the familiar trek to the Boys and Girls Club.

"I still remember some of the counselors who were there, who helped us growing up," Iguodala said. "It was just a great place for us to be, especially kind of the environment we grew up in, it was kind of the escape for us -- which was good for us. I understand what it's like to be a kid there because I was there. So it's easy to come back and try to help out."

Iguodala is at the club to help launch Kids Foot Locker's Fitness Challenge in San Francisco after successful programs in Los Angeles, Atlanta, Chicago and Houston. It's a six-week fitness program that encourages active club members to participate in 60 minutes of physical activity per day, and the club with the highest daily participation increase from the beginning to the end earns a $10,000 prize from the Kids Foot Locker Foundation.

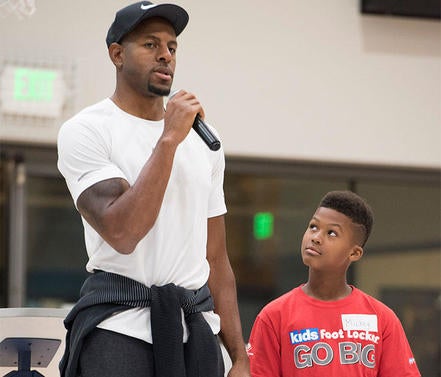

After the fever pitch dies down, Iguodala grabs the mic. There's a podium, but he doesn't use it, preferring to walk closer to the group of children still with their mouths agape in disbelief. Iguodala talks about the program, and stresses the importance of both physical fitness and diet. The kids are hanging on his every word … until Iguodala mentions that they need to cut sugar out of their diets for the duration of the program.

Record scratch.

He's met with the kind of side eye reserved for a parent who just told them, "No video games for a week."

It's a bit easier to swallow coming from Iguodala, whose defined physique can't be concealed by his white Nike Dri-Fit T-shirt, sweater tied neatly around his waist, and black joggers. Whatever Iguodala's been doing has been working, and it's been working for a long time. He's never shown up to camp out of shape. He's also never suddenly found fitness during the offseason and shown up 20 pounds lighter. He's made gradual changes to his diet and workout regimen over the course of his 13-year career to avoid having to make a major overhaul in the later stages. Working with the Warriors training staff over the past few years has been vital to his ability to stay on the court, and stay effective.

"I'm in constant communication with our training staff and our strength and conditioning coaches," Iguodala said. "They're basically like family, you know. I speak more to them than I actually speak to the coaches, which is funny."

After fielding questions from a few of the kids -- "What would you do if you weren't a basketball player?" "What's your favorite sport besides basketball?" "Who do you look up to?" -- Iguodala joins the kids for some basketball drills. Three stations are set up -- two for dribbling, one for defensive slides -- and Iguodala gingerly weaves his way between all three, making sure to take time to talk to the kids.

One girl hugs Iguodala, then runs back to her friends with her mouth wide open and her arm still in the air, as if she'd just been blessed by the pope.

It doesn't take an acclaimed member of the Warriors training staff to see that Iguodala isn't moving well. He was scratched from the next night's preseason finale due to back issues, wearing some sort of contraption around his lower back in the locker room before the game.

"Man, you don't have to come out here and pretend your back's hurt," a reporter joked. "We know it's the last preseason game."

Iguodala defended himself, and the legitimacy of his injury was confirmed when he drew a "questionable" designation for the Warriors' season-opening game against the Houston Rockets.

But while Iguodala is clearly struggling through something at the Boys and Girls Club, he's not letting the kids know. Events like this are part of the reason he made the decision to return to the Warriors this summer, even after Chris Paul, James Harden and the Rockets reportedly wowed Iguodala with "the best recruiting presentation of all time".

"If it's here or anywhere else, you want to make a difference or impact in that community with kids," Iguodala said. "But, you know, the Bay Area I consider home, and my wife is doing a lot of things now within the community, and she gets it as well. This is a special place for us, so I definitely want to continue to reach out to the kids and help them out in any way."

Home.

It's a strange concept for a pro basketball player. After growing up in Illinois, Iguodala went to the University of Arizona before spending eight seasons in Philadelphia, one in Denver, and is now entering his fifth in the Bay Area. Iguodala said he was just kidding when he told reporters over the summer that his son, Andre Jr., started crying when he mentioned they might be moving to another city. But, tears or no tears, his son would have had an adjustment to make.

"He wasn't really crying. I was just getting him back for all the times that he'd drive me nuts," Iguodala said, laughing. "No, he enjoys being here. He's made some good friends, got in a good school, so he enjoys it a lot."

Andre Sr. has also made the most of his time in the close proximity to Silicon Valley, becoming one of the NBA's most avid investors. On his LinkedIn page, "NBA Athlete" gets paltry third billing behind "Entrepreneur" and "Venture Capitalist." The first entry under "Experience" is Iguodala's tenure as vice president of the National Basketball Players Association (NBPA), an office he's held since 2013. In July of 2016, Iguodala used his connections in both the tech and NBA worlds to organize the NBPA Tech Summit, a networking event where NBA players could rub shoulders with prominent members of the tech and venture capital worlds. It's a mission of Iguodala's to help his fellow athletes use their money wisely and prepare for life after basketball.

"It's not just basketball, but just all sports and all athletes -- you know, understanding that they have an influence and how that coincides with a lot of things that are going on in the tech world -- just bridging the two," he said. "It's been going pretty well so far, and I'm looking to continue to build upon that."

Iguodala may not know it, but he's already helped the kids at the Boys and Girls Club become better students. Spencer Tolliver, the Don Fisher Clubhouse director, used Iguodala's appearance as a little extra incentive for the kids to finish their homework in a timely fashion.

"We actually did that for homework time. You do well in homework, you get to go and be a part of this," Tolliver said. My assistant director came in today and she said this was the best -- we call it 'power hour' -- she said it's the best power hour we've ever had."

The parallels between the Warriors and the thriving startup environment that they call home are almost too perfect. Here is a team that practically invented a new way to play basketball by eliminating traditional positions and valuing 3-point shooting, passing and switching, selfless team defense more than traditional one-on-one scoring ability or individual defense. They're also similar to a startup in the way that their competitors have immediately begun to mimic what they do so well, hoping to one day do it better than they do.

The metaphor isn't lost on Iguodala, who knows his particular role with Warriors, Inc.

"Right now I feel like a board member," he said. "I've been doing it for so long, seen everything. I'm making sure we continue to have success late in my career. And when I'm done, just keep this train going. Having that influence, other guys wanting to come play here, getting free agents, you know, this is the place to be. Just trying to be a good citizen I guess."

Part of his role as the elder statesman is to take the young players under his incredibly lengthy wing. For a team that's had as much success as the Warriors have, they are still incredibly young, so it's up to guys like Iguodala and Draymond Green to help keep the younger players in line. Iguodala tends to lead by example and pull guys aside later rather than calling them out during games or practices. But he did admit, ominously, that sometimes he and his teammates are willing to take more drastic measures.

"We got our ways of getting our point across to guys," he said.

Rookie Jordan Bell has seen their more vocal leadership techniques firsthand, and it's not always pretty. Bell, a phenomenal rebounder in college, made headlines for all the wrong reasons when he inexplicably failed to box out during free throws on back-to-back possessions in the Final Four, costing Oregon a potential appearance in the national title game.

Rather than shy away from a sore subject (Bell was in tears as he spoke to the media following the loss), Iguodala and the rest of Bell's new teammates constantly remind him of his momentary lapse by yelling "Box out!" whenever he fails to execute the basic rebounding fundamental during practice.

"Yeah everybody does that," Bell said after his best performance so far as a pro -- a 10-point, 11-rebound showing in the team's final preseason game against the Kings. "What word I should use? It ... reminds me of the one simple mistake -- something you learn when you're younger, just to box out -- you've got to keep track of little things like that, boxing out, two-handed passes. It's the little things you have to keep your mind on, because the littlest, simplest fundamentals like that can cost you a national championship, or at least making it to the national championship."

Iguodala doesn't scream at any of the children doing drills at the Boys and Girls Club, but he does challenge them. After a youngster proudly dribbles swiftly in a straight line, around his partner and back again, Iguodala looks at him and says, "OK, now do it with your left hand." After a quick look of puzzlement, the young boy follows the same path, this time dribbling with his left hand. When he returns, he looks at Iguodala with a sense of accomplishment, waiting to be showered with praise.

"OK, now go between the legs," Iguodala says, smiling.

Veteran leadership is needed now more than ever in the Warriors locker room. The team returns nearly every piece from a dominant championship team that won 67 games despite Finals MVP Kevin Durant missing 20 of them with a knee injury. You'd be hard-pressed to find anyone who watches the NBA on a semi-regular basis who's not picking Golden State to win their third NBA title in four years.

"I think our challenge is more mental now than anything -- being ready from game to game, understanding it's a long season, the ups and downs," Iguodala said. "It sounds funny, but there's a media side to it that can play a part. It can hurt you if you read too much into certain things, but we've got a pretty mentally tough group. We understand -- we've been through it. One or two losses won't make or break our season."

For this team, one or two losses might actually be considered a disappointment.

No matter how this season turns out, however, Iguodala is prepared for life after basketball. He's going to continue with his investment career, and even hinted at a possible run at post-playing career ownership, much like his idol growing up, Michael Jordan.

"It would have to be the right group. I've learned that you've got to group with the right guys -- the right ownership group -- and they have to have the right vision," Iguodala said. "I think being a player and having success, I've seen a lot and been through a lot -- good and bad and in between. I feel like that would be a natural fit, but you've got to get the capital side first, so still more work to do."

Work -- it's exactly what brought Iguodala to the Boys and Girls Club. Yes, it's rewarding -- you can tell he's having a blast with the kids. But putting your 6-foot-6 frame into a car and riding with a sore back from Oakland to San Francisco after practice isn't exactly something one looks forward to. Iguodala will never complain about it because, like he said, he was these kids. He knows exactly how they felt when they saw him walk through the door, and he knows one day it could be one of them walking through that same door to rousing applause.

Nine-year-old Mickey Williams, the self-proclaimed best basketball player at his Boys and Girls Club, could be the next Andre Iguodala. Mickey was lucky enough to stand next to Iguodala and ask him a question in front of the rest of the group, and to hear it from the young man's mouth -- his reaction when he saw one of his heroes walk into his Boys and Girls Club -- tells you everything you need to know.

"I was almost about to cry," Mickey said, as his elementary school bravado melted away and sincerity rushed through. "I don't know, because my dream came true."

This is why Iguodala came to the event. This is why he chose to remain in the Bay Area community into which he's so effectively inserted himself.

This is why he never stops working.