COOPERSTOWN, NY -- Every once in a great while, we hear something that takes our breath away. For Tim Raines, that moment happened on a recent Wednesday morning in Cooperstown.

Erik Strohl, vice president of exhibitions and collections for the Baseball Hall of Fame, had just led Raines, his wife Shannon, his six-year-old twin daughters Ava and Amelie, Raines' agent and good friend Randy Grossman, and two Canadian writers on a tour of the Hall. One final stop remained: The plaque room, where Raines will be immortalized this summer with a plaque of his own, making his induction into the temple of baseball immortals official.

Sensing Raines' excitement, Strohl asks the seven-time All-Star how it'll feel to know that his plaque will hang about 20 yards from the one honoring Babe Ruth.

Raines stops moving, then looks toward the spot where his plaque will hang. His face registers nothing but stunned silence. He shakes his head.

"This is the only thing in baseball," he says, "that's forever."

---

Odds are, you and I probably think about baseball in similar ways. We grew up playing a bit, but we were never good enough to hack it at a high level. So rather than staring down 95-mph fastballs, we watched others do so.

We grew to root for certain teams and certain players, then tried to glean as much as we could from afar. Maybe the voice of Vin Scully, Ernie Harwell, or Dave Van Horne drew us in. If we were lucky, maybe we got to go to the ballpark, watching from the bleachers or the baselines or the upper deck as the action unfolded in front of us. And if we're ever really lucky, we might get a chance to visit the Hall of Fame, to see thousands and thousands of artifacts recounting the history and pageantry of the game, through the accomplishments of the stars who played.

On this April day, I got to experience all of that through the eyes of one of those stars. Making the experience exponentially more special was who that star was. Unlike most fortunate writers who get tapped for the rare chance to accompany an incoming Hall of Famer on his own private tour, I never covered the honoree-to-be for any newspaper or website. In this case I'd be walking a step behind Tim Raines, my favorite baseball player of all time from the time I first started watching the game on my Papa Max's chesterfield, at age 7. If ever there was a time for journalistic objectivity...well, this wasn't it.

Here's what transpired:

-- The 19th century was a very different time for baseball. For a while, the game was played with a five-ball, four-strike count. We saw an 1855 exhibit showing a giant pile of baseballs painted gold, commemorating the winner of every single game played by laborers from the Eckford & Webb shipyard in New York City (that's a lot of paint!). Strohl then explained another 19th-century rules quirk: A player could earn stolen bases for, say, advancing from first to third on a single. That inflated the steal numbers for players of that era...including 19th-century star Billy Hamilton, one of only four players in baseball history with a higher SB total than Raines.

"Cool," said Rock, flashing a knowing smile.

-- We walk to the display showing the first five players to be inducted into the Hall: Ty Cobb, Honus Wagner, Walter Johnson, Christy Mathewson, and Babe Ruth. Raines shakes his head in amazement, sifting through Cobb's unbelievable career numbers, which include 897 steals.

Still, Ruth is the main attraction. Near the first-five display is a huge exhibit reserved entirely for Ruth, one of just two players with their own full-sized exhibits (the other, fittingly, is Hank Aaron). We see a picture of The Babe flanked by dozens of kids clutching the slugger's signature candy bars, and a bulky, headless mannequin donning his famous number three on the back (we learn that the uniform actually comes not from game play but from the 1942 movie "Pride of the Yankees", in which Ruth played himself).

Raines' favorite part of the Ruth exhibit? A photo of the Sultan of Swat sprinting into the right-center-field gap to make a catch...with two hands.

-- The Hall is strict about group size on these all-access Hall tours for upcoming inductees. The typical group will include the inductee, his spouse/partner, the tour guide (usually Strohl, who was as accommodating and gracious as he was knowledgeable), a cameraman for MLB.com shooting quietly over people's shoulders, and a maximum of two writers (in this case myself, and legendary Canadian sportswriter/J.G. Taylor Spink Award winner Bob Elliott).

The addition of Ava and Amelie has turned a fun day into a nonstop parade of smiles and giggles. Here's Amelie miming a violin player and music plays overhead. There's Ava listening intently as Strohl walks us through the display honoring the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League (1943-1954). Here's both of them singing "O Canada" as it pipes through the sound system (their mom Shannon is a proud Ottawan). It's cool enough watching a Hall of Famer's reactions to this intimate tour. It's even cooler watching everything unfold through the eyes of children.

-- The Hall's exhibit on the integration of baseball is huge, and deeply affecting. There's a picture of Fleet Walker, the first black player in Major League Baseball, posing with his wife in 1880. Strohl regales us with stories of barnstorming tours of black players. We learn about Cool Papa Bell, the graceful Negro Leagues outfielder who was so fast, Satchel Paige once declared that Bell could flick the light switch off and be in bed by the time the room went dark. (This oft-told story has a ring of truth to it: Bell and Paige once stayed at an old hotel that had a wonky old light switch that made the room slow to turn dark.)

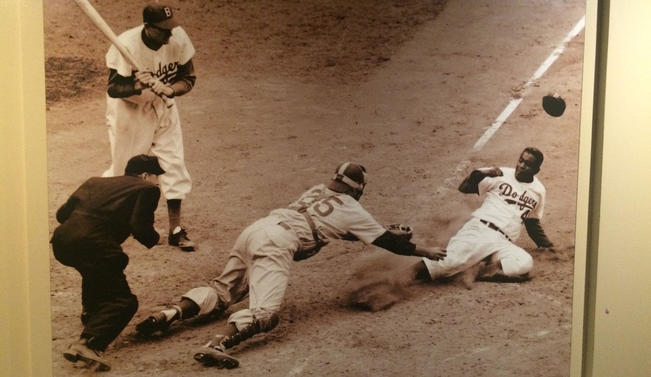

It's when Strohl starts talking about Jackie Robinson that Raines becomes truly enraptured. We see one of the many threatening letters sent to Robinson, donated by his wife Rachel to show how difficult life was for Jackie when he (re-)broke the color barrier, and the uncommon patience and grace that he showed to turn the other cheek again and again. Our guide reminds us that Robinson not only led an influx of hugely talented players into MLB; he and the pioneers who followed in his footsteps also brought a more athletic, more aggressive, more fun style of baseball with them. Meanwhile, Raines has his eyes fixed on an incredible photo of Robinson, in the midst of a hook slide into home.

"I work with Eric Wedge [as minor league instructors and advisors in the Blue Jays system], he's trying to implement the hook slide, trying to teach guys how to do it," said Raines, whose expressive face inevitably perks up whenever the subject of baserunning comes up. "I used to do it at times. Seems like any footage of Jackie that you'd see, he was using the hook slide. So I used to say, 'If Jackie did it, I should try to do it too!'"

Our tour lurches forward in time as we walk. There's a new exhibit honoring players from 1970 to the present that looks like a rainbow exploding on every uniform: Astros orange and Padres brown, and of course those beautiful Expos baby blues. Raines gets fired up about a screen showing an old episode of The Baseball Bunch with Johnny Bench. Bench's teammate Joe Morgan was Rock's favorite player growing up. Morgan calling Raines soon after Rock's call from the Hall in January is a moment that Rock will never forget. Raines starts to tear up just a bit. Dammit, I do too.

There's so much more. Raines' Hall of Fame teammate Gary Carter's mitt. Frank Robinson's Indians jersey from 1975, the year he became MLB's first black manager. There's Raines' batting helmet from his late-career days as a Marlin, the last ever batting helmet without ear flaps on it (they became mandatory in 1983, so Raines was grandfathered in).

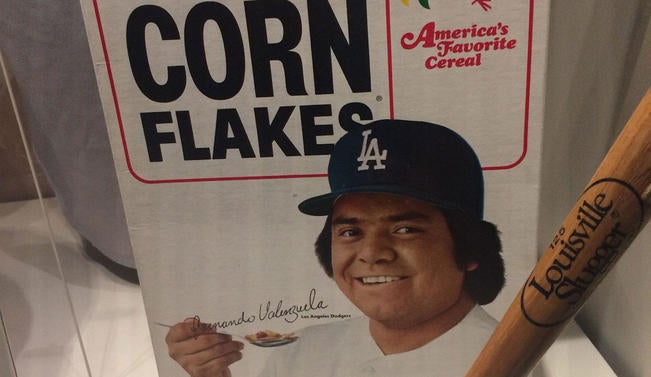

We spot a box of Corn Flakes with Fernando Valenzuela's face on it. Now Raines is half laughing, half pleading his case. "I should have won Rookie of the Year! He pitched like 15 games! But he was in L.A." Rock batted .304/.391/.438 in his 1981 rookie campaign, with 71 steals in 88 games. Valenzuela pitched a lot more than 15 games that year, and was objectively a better player in '81. But it was close.

We turn a corner and come to one of my favorite displays in the whole museum: A glass case containing every season's World Series ring. The first team-issued ring belonged to the Giants, in 1922. Handing out World Series rings became a consistent annual ritual starting in 1931. There are some beauties under the glass, including some dazzlers from the A's teams of the 1970s and the Twins models from 1987 and 1991. The 2003 Marlins ring, by contrast, is a damn monstrosity. It's twice the size of every other ring, garishly designed, and quintessentially Jeffrey Loria-esque.

Raines turns his attention to the three rings he actually owns: the 1996 and 1998 Yankees (he was a key role player and team leader at the start of that dynasty, and Derek Jeter's favorite teammate), and 2005 White Sox, where Raines served as a coach. Within this huge collection of rings, there's one spot left conspicuously empty: 1994.

"Like a spike to the heart," I say. I'll never fully get over that year, given that my beloved Expos owned the best record in baseball when the strike hit.

"Should have been the Expos," said Grossman.

"White Sox!" retorts Raines, who played on the South Side that year, for a loaded, first-place Pale Hose team.

Rock looks at me and starts pointing. Then cackling. The impossibly fast ballplayer I grew up rooting for is also a helluva guy...and a certified joker.

Down the stairs we go, to a special room closed off to the public. It's hidden and mysterious, and can only be accessed via coded key card. Strohl swipes his card. Walking in, we see rows and rows of boxes, contained within rollaway walls on our right that stretch as far as the eye can see. It looks a little like the archives vault where they store the ark at the end of "Raiders of the Lost Ark".

For every one of these tours, each pending Hall of Famer gets to view about a dozen precious items. Some are rare artifacts that are there just because they're incredibly cool. Others go on the display table because they'll resonate based on that player's own accomplishments and connections in the game. We're all told to put on special protective white gloves: Touch any of these items as much as you like, just don't damage them.

Raines picks up two gloves. They're meant to be catchers' mitts, though they're so tiny, you wonder how they offered any kind of protection. A little further down, two more gloves -- one belonging to Lou Gehrig, the other to Derek Jeter. There's a pair of hats perched side by side. One is Ozzie Smith's from his last All-Star Game, while the other is a rare eight-panel hat from the Negro Leagues, worn in the 1930s by an old third baseman named Dave Malarcher.

Strohl tells the story of one particular ball sitting on the viewing table. In the 1941 All-Star Game, Ted Williams launched a home run that struck the facade of the upper deck in right at Tiger Stadium, then bounced back onto the field. Playing right for the National League that day was Enos Slaughter. When the ball came to a stop near his feet, Slaughter picked up the ball. Then he hung onto it. Forty-four years later, at his own Hall of Fame induction ceremony, Slaughter walked up to The Greatest Hitter Who Ever Lived. He reached into his pocket, and pulled out the ball from 1941. I think this, Slaughter told the Splendid Splinter, belongs to you.

Raines moves on to handle a series of bats. There's a 40-ounce bottle bat used by former Reds and Giants third baseman Heinie Groh, the bat so named for having a giant barrel, without anything resembling the gradual tapering off you see on modern bats. There's a bat belonging to Frank Thomas, one of Raines' best and most beloved White Sox teammates. A Ted Williams model, which causes all of us to go silent for a second, out of reverence. And the coup de grace, Babe Ruth's lumber, a 36-ounce model from 1930.

"Why couldn't we have wood like this?" said Raines. "They don't make them like this anymore."

Sprinkled in between are several Raines mementos. The cleats he wore in 1995 when he set the American League with the White Sox for most stolen bases (you can still see the dirt and gum stuck to the bottom -- the Hall tries to leave every piece exactly as worn on the field). The actual base he stole to reach 500 for his career. Plus items from his fellow Expos Hall of Famers, including the bat Gary Carter used to hit two home runs in the 1981 All-Star Game, and an impeccable jersey belonging to Andre Dawson, Raines' Montreal teammate who helped straighten out Rock's life after cocaine abuse nearly wrecked his career in 1982. Raines never forgot the gesture: His two sons by his first marriage are named Tim Jr. ("Little Rock") and Andre ("Little Hawk").

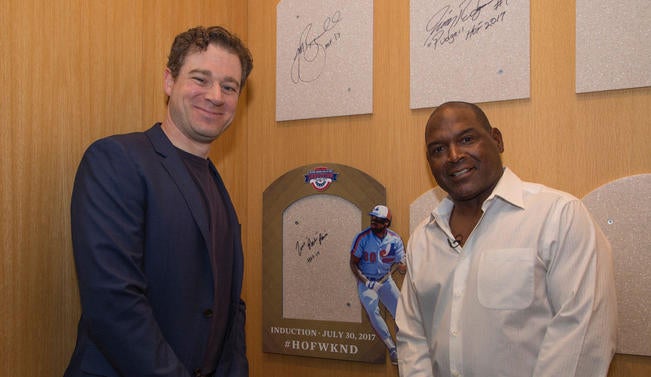

One last stop remains: the plaque room. Raines takes his time wandering through. He stops to give the Joe Morgan plaque a thorough read. He walks by Ruth and Cobb, Mays and Mantle, Koufax and Pedro. At the end of the big wall sits the plaques that will honor this year's honorees: Jeff Bagwell, Ivan Rodriguez, John Schuerholz, Bud Selig, and Raines. There's a little border around the white frame where the plaque will be installed, with a photo of Raines in his Expos blues from the 80s.

Jon Shestakofsky, the Hall's vice president of communications and education, hands Raines a marker. The Hall has implemented a new policy, granting inductees a chance to sign underneath where their plaque will sit for all time. He carefully takes the marker and signs it.

Tim "Rock" Raines

HOF 17

We're all getting ready to leave, when Bob Elliott approaches Raines. Would Rock be willing to stand next to the space where his plaque will go, and pose for a picture? Bob then looks at me. "Now go stand with him."

Being a sportswriter is a terrific gig. You get to learn about the games you love, grab readers by the hand, and take them with you as you explore new ideas together. I'm grateful for every minute that I get to do what I do. Watch this short clip the MLB.com videographer put together, and you'll see why.

But every once in a while, everything can become...a little too close. We're told never to cheer in the press box. We're urged to always remain impartial. We're taught that the story is never about us, that it's about the players and teams that we're paid to cover.

What do I do in this moment? This is Raines' day, why am I even here? I can't ruin this for anyone. I'm going to politely decline, and go stand in the corner.

"Come on over, man!" Raines exclaims.

I walk over. He smiles. We pose.

I hope all of your childhood heroes are this kind too.