Throughout a mercurial 30-fight pro career, lineal heavyweight champion Tyson Fury has employed a shifty, defensive style to remain unbeaten. The self-proclaimed "Gypsy King" has been just as elusive for journalists seeking his true thoughts given how often -- sometimes in the same interview -- the bombastic Fury will contrast himself using the same playful tone.

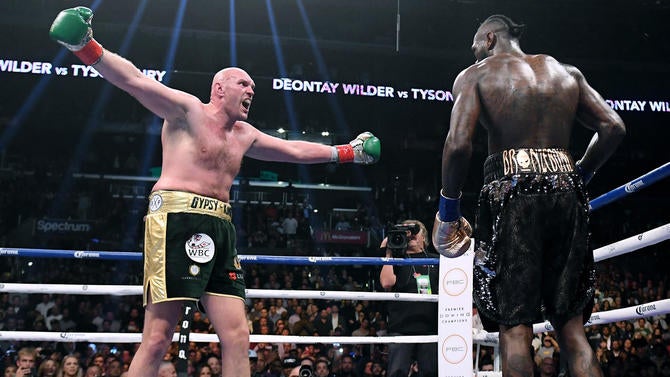

So when Fury (29-0-1, 20 KOs) boldly declared at last month's kickoff press conference that he would be eschewing his plans to box WBC champion Deontay Wilder on Saturday in their pay-per-view rematch in Las Vegas (Fox and ESPN+ PPV, 9 p.m. ET) and predicted a second-round knockout win, few -- if any -- took him seriously.

One month later, Fury hasn't stopped predicting a KO and has doubled down at every turn. What it produced is the most intriguing storyline entering such a historically important second fight: Is the U.K. native and descendent of Irish Traveller bare knuckle champions actually crazy enough to walk down boxing's most dangerous puncher? More importantly, is there any way he can actually pull it off?

Respect box? Subscribe to our podcast -- State of Combat with Brian Campbell -- where we take an in-depth look at the world of boxing each week.

The 31-year-old Fury has never been known as a finisher despite his 6-foot-9 frame. Wilder (42-0-1, 41 KOs), meanwhile, has only gone the distance twice in his career -- because of a broken hand against Bermane Stiverne in 2015 (avenged via first-round KO in the rematch) and once more in 2018 when Fury dramatically rose from a second knockdown in Round 12 to salvage a disputed split draw.

Yet just about every interview Fury has given over the past month, the same question has greeted him to kick things off: Will you really try and exchange with Wilder at close range or is this some kind of mental ploy?

"They won't have to wait long to find out, will they?" Fury told CBS Sports during last week's media conference call. "It's not very long to see whether I'm bluffing or telling the truth. This is boxing and many people have said many things in the past but how many of them have been man enough to back it up?"

Among the many intangibles that make Fury so unique -- from his sublime speed and agility for his size to his miraculous comeback in 2018 from a three-year retirement and subsequent battles with drug abuse, mental-health issues and obesity -- it's his audacious lack of fear that makes you want to believe this is anything but another mind trick.

Unlike the build to their first fight in which the trash-talker tried his best to get inside Wilder's head with behavior straight out of the Muhammad Ali playbook, Fury has been noticeably toned down and confident over the past month. Even Wilder has been confused when asked about Fury's intentions.

"To be honest, I don't know what he is going to do. Fury [is] crazy, man. He is one way one minute and one way the next," Wilder said during their second January press conference in Los Angeles. "With the strategies they got coming up with I don't know how to take it. I don't know if they are trying to throw me off my game."

Getting back to his roots

Even with Fury's history of floating so boldly between behavior that's outright crazy and more strategically placed under the guise of "crazy like a fox," his recent decisions seem to back up his words. The biggest announcement came in December when Fury, just two months out of the biggest fight in his career, parted ways with trainer Ben Davison in favor of Kronk Gym disciple SugarHill Steward (formerly Javan Hill), who is the nephew of the late Emanuel Steward.

In 2010, a 21-year-old Fury arrived unannounced at Kronk in Detroit as an unknown and earned his stripes so quickly that he went on to spend a month living in Emanuel's house and picking his brain. The Hall of Fame trainer, who guided legends like Thomas Hearns, Lennox Lewis and Wladimir Klitschko, went on to say in interviews before his 2012 death that he believed Fury would become heavyweight champion one day -- a feat he accomplished by upsetting Klitschko in 2015.

Andy Lee, a former middleweight champion and Kronk fighter who is also the cousin of Fury, joined SugarHill to make up the new corner as Fury purposely sought to change his style from one built around feinting, which frustrated Wilder in 2018, to one in which going for the knockout was the central focus.

"That's what Tyson wants, he wants that Kronk style. He wants a knockout," SugarHill Steward told IFL TV in January. "He wants to be able to use his right hand like a Thomas Hearns, like a Wladimir Klitschko, like a Lennox Lewis, like a Gerald McClellan and so many of the famed Kronk fighters throughout history. The Kronk fighters have always been able to set up that big shot and get the knockout.

"I don't want Tyson Fury to win on points, we are knocking Deontay Wilder out."

Although most observers felt Fury had done enough to win a decision in the first fight with Wilder, it was the judges' scoring that "played a massive role" in planting the seed to alter his strategy.

"It was almost a blessing in disguise that I didn't get the decision because I would've kept working on my boxing," Fury said. "I believe I can outbox Deontay Wilder very comfortable but the fact of the matter is, I boxed him comfortable last time. It's not up for me to believe it, the judges have to believe it. To guarantee a victory, I have to get a knockout. I don't want to leave anything unturned this time. I don't want to get another controversial decision. I want it to be a defining win either way."

"I'm not a judge and these guys see what they see. That's their opinion and that's what they get paid to do. But in order to guarantee a victory, my own destiny lies in my own two fists."

Although Fury hasn't alluded to it publicly, there's a wonder as to whether his most recent outing against a virtual unknown in Otto Wallin also played a role changing him. Fury suffered a nasty cut above his right eye early in the fight and was forced to transform into a stalking slugger out of fear that the fight would be stopped.

Fury not only fought well on the inside, he used his weight advantage to lean all over Wallin in an effort to wear him out. Although Wilder is 6-foot-7, he weighed in at a svelte 212.5 pounds for the first fight. Fury, who weighted 256.5 pounds, says he has added 14 more for the rematch and could end up holding more than a 40-pound weight advantage should he employ the same strategy against Wilder.

As far as the not yet fully healed wound above his eye is concerned, Fury has also brought in veteran cutman to the stars Jacob "Stitch" Duran. Fury has also conceded that the cut could very well be opened back up early, which only doubles down on the idea that seeking an early knockout might legitimately be Fury's plan.

A necessary change?

For those questioning the sanity of Fury going on the offensive, there are some stylistic advantages to consider. Although Wilder can end a fight at any point given his supernatural power and underrated conditioning, his rudimentary technique has held him back from ever proving he can fight on the inside or have success when backed up.

"There's always a risk when you get in the ring, period, especially in the heavyweight division where one punch can change a fight," SugarHill Steward said. "You take a risk by not stepping on the gas and [not trying] knocking your opponent out because later on in the rounds maybe he knocks you out. That's the risk Tyson took by not trying to knock [Wilder] out in the first fight and trying to win on points. He doesn't want that again and I don't want that again.

"I wasn't raised that way. Emmanuel always taught me, 'Get the knockout. That's the only 100 percent sure way you win the fight. Take it out of the hands of the judges.'"

Another avenue of motivation for Fury is his belief he had Wilder hurt on more than one occasion in the first fight but wasn't able to follow up out of fear that he wouldn't have enough stamina to go the 12-round distance. Wilder has disputed this belief, referring to Fury's power as "pillow hands," but Fury believes his technical advantages will help set up a finishing blow.

"I learned that Wilder can be hit and that he can be hurt," Fury said. "He has a big right hand and that's it. He's a one-dimensional fighter and I'm going to prove that. Now I know I can do the distance and when I get him hurt, I'll throw everything but the kitchen sink at him and he won't be able to take it."

The real root of Fury's decision, however, could come down to the fact that he knows he's unable to truly be at his best unless the odds are stacked against him. It's a wonder Fury has stayed unbeaten given his constant battle with weight, depression and substance abuse, including the fact that he so often plays up or down to the level of his in-ring competition.

Yet when given no shot against Klitschko in 2015, Fury showed a level of focus and precision we had never seen from him before. The same can be said for his performance as an underdog against Wilder the first time. Oddsmakers have had made Saturday's rematch a veritable pick 'em fight with Fury installed as a slight favorite on some books.

Did Fury willingly sign up for such an impossible task of finishing Wilder, who has never been knocked down as a pro, simply to access a level of motivation that couldn't otherwise be faked? It's an interesting psychological experiment, if so. Pulling it off could further launch Fury into the status of historical folk hero given how dramatic the twists and turns of his career have gone up to this point.

It's why counting Fury out or dismissing the intentions of his words can only be done at your own peril, whether you're a fan, critic or even Wilder himself.

Going for history

There's a magic surrounding Fury that is rarely seen at the highest level in combat sports. From his improbable rise off the canvas in Round 12 against Wilder to his ability to boldly call his shots and somehow back it up, comparisons can be made to Conor McGregor's initial UFC run or the second half of Ali's career in the 1970s.

"I think Tyson Fury can be placed as one of the great fighters [of all-time] because what he has done already by dethroning Wladimir Klitschko and to come back to boxing after taking off all the time that he did and to make an instant classic with [Wilder]," SugarHill Steward said. "Nobody gave Tyson Fury really a chance in that fight and to come back and make a performance like that, it still reminds me of Muhammad Ali. People didn't think he could do what he went on to achieve after being off for some time and now you have Tyson Fury in that same situation with that same charisma and character and confidence."

Should Fury actually win by stoppage, the comparisons to Ali's upset of George Foreman in their 1974 "Rumble in the Jungle" classic will be inevitable. Make no mistake, the task ahead of him will not be easy, especially considering one misstep could have Fury looking up at the lights.

Still, when asked whether Fury believes that Wilder is, indeed, the most devastating puncher in boxing history, Fury disagreed.

"I felt the power -- ain't so bad, ain't so bad. He can't be the biggest puncher in history because he couldn't knock the 'Gypsy King' out, could he?" Fury said.

"The one who should be concerned is Deontay Wilder. He landed the two best punches that any heavyweight in the world could ever land on someone else and the 'Gypsy King' rose like a phoenix from the ashes back to me feet and hurt him at the end of the round.

"This is heavyweight boxing. I've been hit, I've been hurt and I've been put down in my career but it's not when you get put down, it's what happens when we get back up and keep moving forward."