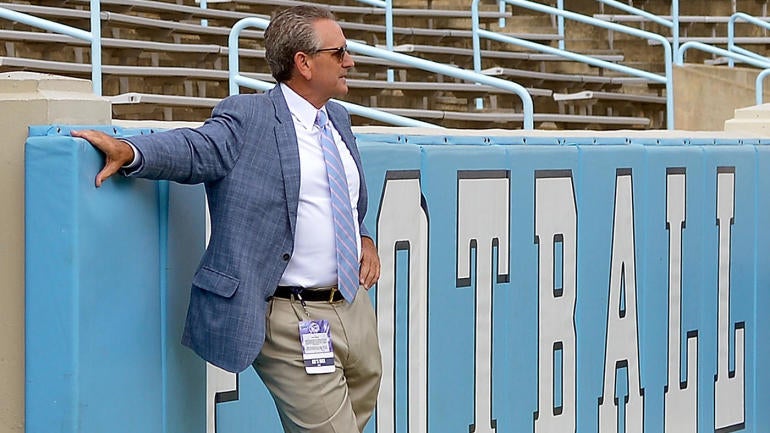

North Carolina athletic director Bubba Cunningham warned this week that athletes would be professionalized if current name, image and likeness legislation is adopted, a move he said would be against the core of the NCAA mission.

Because the NCAA has not been more proactive in the ongoing debate over name, image and likeness rights, Cunningham believes the national office in Indianapolis has become increasingly distant to the more than 1,100 member schools.

Cunningham spoke with CBS Sports after we obtained a letter in which he expressed concerns over recent NIL recommendations from the NCAA's Federal and State Legislation Working Group.

"The membership is further and further away from Indianapolis than we've ever been," Cunningham said. "What we do is end up accepting what comes our way and then trying to deal with it. That shouldn't be the way it works. More people are raising their hand saying, 'This really doesn't make sense to me.'"

The five-page letter went to the Uniform Law Commission, a 128-year-old body that helps draft legislation to bring uniformity among laws in all 50 states and U.S. territories. The letter argues strongly against NIL and for the NCAA status quo.

In part, it reads: "Despite public pressure that has been exerted on NCAA leaders … we urge those involved in the ongoing legislative conversations not to abandon a model that has provided educational and athletic opportunities for hundreds of thousands of student-athletes."

Continuing a sweeping philosophical change, that working group last month began developing NIL legislation that will allow athletes to be compensated for their autographs, business ventures and social media influence.

In some cases, that compensation would be generated because of athletes' on-field talents. Cunningham said that would be a step toward making them professionals. He referenced a recent conference call with ACC athletic directors.

"Since that phone call, I've had a lot more ADs say, 'We agree, this is way too far. If this is what you're recommending, what didn't you recommend? If we go down this path, we've … professionalized the college student,'" he said.

Cunningham said he told a member of that working group that he could not support any of the proposed NIL changes. He does support the NBA's G League that has become a minor-league alternative in basketball for those wanting to turn pro.

"We need more choices for people that don't want to participate in [the collegiate] model," Cunningham said. "I wish we had something for football right now."

In his ninth year as North Carolina's AD, Cunningham is one of the most respected figures in college athletics. He said schools are increasingly being told by the national office what's going to happen instead of being included in a wide-ranging discussion.

"I don't feel like many of us are engaged at that [national] level. This governance structure is one in which where you seem to be given the outcome," Cunningham said.

Ironically, Cunningham is criticizing the NCAA at the same time he is supporting that collegiate model the association has so doggedly defended. It is because of a series of legal defeats and lack of foresight that critics say the NCAA finds itself painted in this corner.

That is, having to give away one of its central tenets -- allowing athletes to be paid by a third party -- rather than find itself in another long legal battle.

"There are 5,000 professional athletes," Cunningham said. "There are 500,000 student-athletes. What we do is vastly different than a professional model. … The professional model is about for-profit for owners and participants. The models are vastly different."

That statement comes at a crucial time for the NCAA. In what is one of the most significant moves in NCAA history, the association is currently seeking an antitrust exemption from Congress to implement NIL. The NCAA had previously stiff-armed any federal intervention in its business. Now, it desperately seeks help from Congress.

An antitrust exemption could conceivably limit the amount college athletes could earn.

The Power Five commissioners seemed to leapfrog past the NCAA last week in writing to Congress directly asking for help.

"That's an acknowledgement in there that Congress doesn't really want to hear from the national office," Cunningham said. "They want to hear possibly from the conferences, but they are more interested in hearing from the schools."

One question facing the NCAA is whether Congress is even interested in bailing out the association. Critics point out the NCAA is in this situation after losing a series of landmark antitrust lawsuits. It has no choice but to implement NIL legislation or face more lawsuits.

Even if it develops its own legislation, the NCAA faces a soft deadline of July 1, 2021, should Congress does not step in. That's when the State of Florida's NIL bill goes into effect.

At that point, the NCAA would face having to fight or let stand similar bills in dozens of states that are more athlete friendly than the NCAA's version of NIL. California was the first state to adopt NIL rights; however, its law will go into effect in 2023.

"For one reason or another, the NCAA has chosen not to [challenge those states], which I don't understand," Cunningham said. "Stand up for your values. If you lose the lawsuit, you lose the lawsuit, but I'd rather be sued over my values than capitulate to something I don't believe in."

As recently as last fall, the NCAA was taking a hardline stance on NIL. Now, it is asking for federal intervention in an election year amid a pandemic and nationwide protests.

Given those issues, there is doubt whether there is the political will on The Hill to take on NIL at this time.

During a recent visit to Washington, D.C. to meet with legislators, Cunningham said, "Eight out of 10 I talked to said, 'This isn't a federal issue. Don't come to us to solve your problem.'"

"My hope between now and October is that we can build enough of a consensus that this is a bad idea. We won't adopt this legislation," he added.

A final report from the working group will be delivered in October to the NCAA Board of Governors.

In Cunningham's letter to the commission, he and UNC associate AD Paul Pogge lay out specifics for keeping current amateurism rules. They noted the Division I Student-Athlete Advisory Committee said in October NIL would mean "significant harm to college athletics."

The letter also argued that NIL would put the newfound riches in the hands of a "select few" athletes in football and basketball. Corporate sponsors would begin gravitating toward individual athletes instead of the institutions. It also warned of more agent influence.

What no one is able to figure out yet is recruiting in an NIL world. The letter referenced what has become a buzzword -- "guardrails" erected around legislation that would prevent improper recruiting inducements.

"We do not want to live in a world of crowdfunded recruiting in which boosters have direct access to buy top talent or can easily disguise their attempts to do so," the letter stated.