ATHENS, Ga. -- You look like you know what you're doing.

That's a compliment -- I think -- paid to me by Kirby Smart in front of God, country and Sanford Stadium came before the start of Georgia's spring game on Saturday.

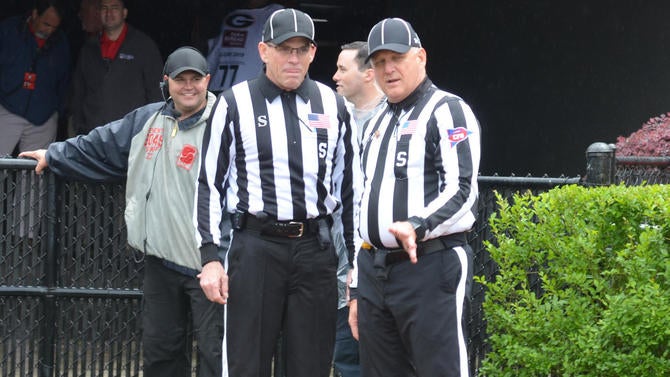

Maybe the uniform had something to do with it. The assignment was agreeing to help officiate G-Day, one of the school's most cherished traditions. The SEC extended an invitation to a few media members to mix with an its officiating crew for an afternoon -- sort of walking a mile in their (turf) shoes.

It is a win-win for both parties. The SEC gets to show its best side -- an inside look at officiating in the nation's best conference by what may be some of the nation's best officials. We get a story. This is mine … and theirs.

I was shadowing side judge Rob Skelton. The 61-year-old banker had driven 234 miles from his home in Lincoln, Alabama.

Skelton does that on most weekends in the fall of officiate games. He loves what he does. His dad played quarterback for Alabama. Rob is a good, decent man injected with Southern football fervor. Like his peers, he certainly doesn't work SEC games for the money.

One official told me he netted $8,000 last year officiating a season's worth of SEC games. That includes game checks that can range from $1,900 to $2,225, according to 2018 figures obtained by CBS Sports. That doesn't include unpaid film study during the week done on each individual's time.

SEC officials also get a per diem/travel allowance that sometimes doesn't cover all the expenses.

Fans can scarf up cheap airfares and hotels the moment the schedule comes out. Not so much for officials who sometimes get their assignments a few weeks before a game.

Try getting flights or a room anywhere near Tuscaloosa, Alabama, or Gainesville, Florida, or Athens for a decent price two weeks before a big SEC game. Officials double up in hotels to save money.

That begs the question: Why doesn't such a rich conference pay more for one its most valuable commodities?

The answer is supply and demand. If you have a problem with your pay, there are "86 guys" waiting in line to take your job, one official told me.

"It still comes down to your passion," SEC official Tom Quick said. "Whatever that is, it's [great] to go work the coolest the games. You're there because you can see the camaraderie that goes on."

That was evident in our brief dive into that officiating world. Guys are busting chops all the time. There really is a relationship between coaches and officials in the SEC. Those coaches see the same faces each week. There is a certain comfort that comes with that.

"Don't let them screw up my spring game," said Smart when chiding SEC coordinator of officials Steve Shaw, who informed the Georgia coach that the media were infiltrating.

I hope we didn't. SEC observer and instant replay coordinator Larry Rose certainly didn't hold back. Rose knows he is the officiating version of the strict schoolmarm. The man is noted for his, um, scrutiny of the officials he oversees.

"Within two weeks time I got this reputation, 'We're going to be there a long time,'" Rose said of the officials. "My first [post-game evaluation] lasted almost two hours."

Rose had a legal pad-full of our mistakes waiting for us media hacks in his post-game debrief. One of us missed an intentional grounding. One us of called a phantom holding.

Rose kind of raised an eyebrow when he flagged a piece of replay showing me laughing on the sideline. Bad form, believe me.

ESPN sportscaster and back judge Sean McDonough bailed me out by calling a pass interference in the end zone that I didn't see.

Skelton was encouraging as I tagged along like a lonely puppy. He showed me how to backpedal, how to turn, how to get the hell out of the way.

He boiled down the task by asking me how many college football rules there were.

"Twelve," Skelton reminded.

True, but it takes 214 pages in the NCAA rule book to explain them.

"You ready?" Skelton said. "Let's have fun."

It was informative, invigorating and a relief when it was over. My biggest accomplishment may have been not becoming an embarrassing viral meme.

Did I at least look like I knew what I was doing?

"I don't know about that," I told Smart.

Here's what else I learned: The real officials really are underpaid and overworked. They undergo criminal and financial background checks. They have to pass physical tests each year.

It's harder than ever to officiate. Tempo offenses have caused officials to make quicker decisions. Never mind having a Skycam looking over their shoulders. Shaw is scared witless about the specter of gambling. He brings an FBI agent in each year to speak with his officials.

"Integrity is the bottom line of everything," Shaw said. "… Gambling is a pervasive thing."

It all can be undone because of the ever-present possibility of a blown call.

It happens. They will happen in the future. But we, as a society, changed long ago. When did simple anger over State U getting jobbed turn into sadism?

"If you make an incorrect call, [it can be with you] the rest of your life," Shaw said.

He was our Sherpa for the weekend. Shaw was the "white hat" -- referee -- for the spring game. He spent 15 of his 21 years officiating in the SEC. Since 2016, Shaw has also been the NCAA secretary-rules editor, basically the sport's head rules arbiter.

His passion is clear for a job that he says is increasingly becoming hazardous work. The SEC is concerned at the way its officials were treated in last year's epic seven-overtime classic between Texas A&M and LSU.

Not necessarily at the game. There's no single bogeyman out there, just the acidic social media bile that emerged over the course of 255 plays and almost five hours.

No wonder we got the usual police escort to the game.

"The fans didn't know the difference out there between you guys and us," one SEC official told me. "They don't know the difference between any positioning and responsibilities. That's why the referees get so much [criticism]."

I didn't need the SEC Official Experience to be convinced of the hazards. These businessmen, bankers and insurance salesmen have day jobs. They also have to support and nurture their families.

They don't need all the ancillary crap. They also can't give it up. The juice is too intoxicating. Skelton nodded when I asked him if part of the attraction was being in control of such a huge, important enterprise.

They also know all of it can go poof in a second. That's the nature of fans and their most deadly tool -- hiding behind e-anonymity.

There is concern in and outside of the SEC about what one official called the "tribal world" of biased, often-clueless fans.

J.C. Louderback had his life altered inexorably. He was the referee in the Missouri-Colorado Fifth Down game that changed officiating and how we view it forever.

That day in October 1990, everybody on the field who should have known they were on the fifth down screwed up -- the officiating crew, the chain gang flipping the down markers, even some Missouri coaches and fans. To the point, a group of Missouri students began tearing down the goal posts.

Colorado won the game with the help of a fifth down. Louderback's Wichita, Kansas, home was inundated by hate mail and calls.

The Big Eight didn't renew his contract. Louderback was relegated to doing games in smaller conferences. His reputation was never the same. His life was never the same.

Remember, this was in a time before Louderback's account could have been hacked, his name smeared throughout the webscape. It has been almost 29 years ago.

My officiating career was over after Saturday's spring game. The guys we shadowed, it's in their blood. Considering the pay, the time, all that ancillary crap, officiating is definitely a vocation.

They should be admired, valued, paid more.

Just don't miss a call, fellas. Please.