Nearly a full 45 years later, and despite generations of great racers and great moments that followed in its wake, the aftershock of the 1979 Daytona 500 is still felt each February at the open of Speedweeks. In many circles, it is regarded as the most pivotal race in the history of NASCAR. In some circles, it is regarded as the single greatest NASCAR race of all-time.

Before a live television audience -- many of whom were stuck at home due to a massive snowstorm along the east coast -- NASCAR was launched from a regional racing novelty to national relevance and reverence as Donnie Allison and Cale Yarborough took each other out racing for the win on the final lap, opening the door for Richard Petty to hold off Darrell Waltrip to win his sixth Daytona 500 and drive to Victory Lane as Yarborough and the Allison Brothers fought each other in the infield. For much of America, it was their introduction to the very essence of stock car racing itself -- and for CBS Sports, it made for quite the first impression.

From the first live, flag-to-flag broadcast of the Daytona 500 in 1979 onward], CBS Sports spent 21 years as the race's television home and would come to play an enormous role in shaping the lore and mythos of "The Great American Race," as well as forever changing the way NASCAR was presented on television and how the story of the race and the stories of its drivers were told. This year, CBS Sports spoke with several who were involved in the network's Daytona 500 broadcasts about their lasting impact on NASCAR, from the Hall of Fame broadcaster who drove them forward to the technical and storytelling advancements still felt today.

Ken Squier's impact and influence

Compared to the decentralized and often chaotic sports media landscape of today, the 1970s presented a much simpler time for many sports on television. While major sports such as NFL football, Major League Baseball and NBA basketball were taking hold as network staples, many other sports were presented in condensed, edited-for-TV formats on programs such as ABC's "Wide World of Sports." These programs marked the first exposure of many to NASCAR racing and its biggest race, the Daytona 500, which had come to be featured annually on Wide World of Sports.

But in the late 1970s, CBS Sports began executing a strategy to cut into the dominance ABC had enjoyed over sports media, and focused specifically on Wide World of Sports events that the network could pick up by promising the rights holder either expanded tape coverage or live coverage outright.

The Daytona 500 was identified as one such event that fit into this strategy. But actually bringing the Daytona 500 on CBS to life was largely the work of one man who was in a unique position to bring NASCAR to the masses.

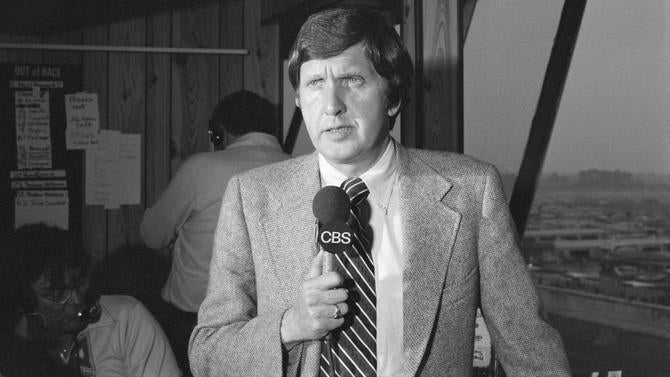

In CBS' employ as a sports broadcaster was Ken Squier, a racing broadcaster from Vermont who had spearheaded efforts to produce and broadcast national radio broadcasts of NASCAR races as the co-founder of Motor Racing Network. A racing insider with influence extending all the way up to NASCAR founder Bill France Sr. and president Bill France Jr., Squier would come to serve as the single most important advocate for stock car racing at CBS, fostering an important connection between CBS executives and the France family.

"The idea to steal the Daytona 500 was Ken's," said Neal Pilson, former president of CBS Sports. "Ken came to Barry Frank and to me and said, 'I have it on pretty good authority that Bill France is looking to show the race live. And if we, CBS, would agree to that, I think we could make a deal.'"

The process of acquiring the rights to the Daytona 500 took several years, and there were several hurdles to clear on both the network's side and NASCAR's side to make it possible. At CBS, skepticism lingered over the feasibility of having a live broadcast for a four-hour, unscripted event with no real time constraints, and also whether NASCAR -- which to that point had little reach outside of the southeast -- would be accepted by a mass television audience, CBS affiliates, or their advertisers. Meanwhile, NASCAR brass had its own concerns about how a live television broadcast would impact at-track ticket sales, the sport's primary source of revenue.

After negotiations spanning half a year, which included the condition of a regional blackout in Florida, CBS Sports agreed to a five-year contract with International Speedway Corporation to carry the Daytona 500 live on television in May 1978. Squier would serve as lead announcer, accompanied by analyst and British racing star David Hobbs in the booth, former NASCAR Cup champion Ned Jarrett and Brock Yates as pit reporters, and Marianne Bunch-Phelps as a roving reporter. The deal was consummated with a celebratory meal at the Steak 'n Shake on International Speedway Boulevard in Daytona -- a France favorite -- that came out to approximately $6.40.

Neat piece of @CBSSports company history. This is the press release announcing they'd broadcast the Daytona 500 for five years starting in 1979 pic.twitter.com/qA1vQXzLrV

— Steven Taranto (@STaranto92) May 30, 2023

Production talent for the Daytona 500 included Mike Pearl, who achieved industry fame as the producer of "The NFL Today" on CBS, and others like director Bob Fishman and Bob Stenner who later succeeded Pearl as producer. But much of the vision for the Daytona 500 on CBS was Squier's -- with many of his willing students on the production team new to broadcasting racing, a great deal of Squier's work centered around teaching them what made for a comprehensive racing broadcast and how to best show and tell both the action on the racetrack and the drivers behind the wheel.

"He was instrumental in everything in the early years. Feature ideas -- 'This is a great story with so-and-so' -- the rivalries, he was the one who said, 'We need to get down into the pits more. We have to explain what's happening with a tire change, what everybody on the crew does,'" Fishman said of Squier. "We started doing interviews down there, showing the incredible trailers these guys live in when they're down there for Speedweeks ... He was our silent leader. He was quiet, but a guy who knew what he wanted and knew it would make the sport better. And he was right."

"He was kind of, television-wise, the face of NASCAR," Stenner said of Squier. "So through him, he introduced me to a lot of the car owners, drivers, crew chiefs, where I could go down to the garage area and kind of know my way around and know the people I needed to talk to. But I listened to him totally. ... I can't tell you how much credit he deserves."

The famous finish to the 1979 Daytona 500 would see Squier's influence on the production team play out in real time and in dramatic fashion. Because Donnie Allison and Cale Yarborough had built up such a massive lead over the rest of the field by the final lap, cameras were not on the three-car group of Richard Petty, Darrell Waltrip and A.J. Foyt when Allison and Yarborough crashed in Turn 3.

The production crew had to scramble to try and identify third place on back, and at one point a cameraman mistakenly picked up the car of Buddy Arrington -- who ran cars purchased second-hand from Petty Enterprises and painted identically -- before Squier gave direct instructions as to where the race for the win was ("They're still up in Turns 3 and 4! THE LEADERS ARE UP IN TURNS 3 AND 4!").

"I take a shot of Arrington thinking it's Petty, and it's not. And Squier keeps pleading with me over the air ... And now I realize, 'Oh s--t, I gotta get this camera to Petty,'" Fishman said. "And that's how we got Petty crossing the finish line, and then of course we go right back to the fight because now they're out of their cars punching each other. It was mayhem, and Ken Squier saved the show. Because if it wasn't for him, I may have stayed on Arrington and I would've lost Petty coming to the finish."

The visuals of the final lap of the 1979 Daytona 500, and everything that happened afterward, are now permanently etched into the minds of race fans and made for a seminal moment in NASCAR's history. The sport had become viable as a national sports property, and one CBS had taken the lead on.

"We looked at each other saying, 'It can't get any better than this,'" Pilson said. "It was a lot of luck and a lot of skill and a lot of planning -- quality people in place -- and it turned out to create a whole new marketplace for NASCAR racing."

Technical innovations

From the 1979 race onward, the deployment of cameras across the Daytona International Speedway expanded as the production crew tried to find ways to both show the audience the action on-track as well as provide them with a sense of speed. One important concept, an in-car camera, was featured in the 1979 broadcast aboard Benny Parsons' car. The camera was somewhat more developed and less cumbersome than previous iterations of onboard camera, but it came with limitations: The camera sat in a fixed position, and its pictures could be unreliable when Parsons drove toward the backstretch and began losing signal from CBS' production compound behind the frontstretch grandstands.

Then, in the early 1980s, Bill France Sr. acquired a tape from the Hardie Ferodo 1000 at Bathurst in Austrlia and passed it along to Mike Joy -- who later became a pit reporter and lead announcer for CBS, and who has since served as lead announcer for all Daytona 500s on Fox from 2001 onward -- at Motor Racing Network. Interested, Joy began watching the tape, which featured an in-car camera unlike anything he or Squier had ever seen.

"They cut to the onboard camera ... As he comes up to make a pass on another car, the camera pans. And this was something we had never, ever, seen before," Joy said. "And I got right on the phone to Waterbury, Vermont to call Ken. Ken wasn't there. He was right across the street from me meeting with Bill France Jr. I call over there -- 'Well, y'know, they're in a meeting.' 'I'm sorry, you've got to interrupt him.' And I said, 'Before you leave, you have got to come over to my office, you have to see what I've got here.'

"And he saw it and had the same reaction I did. A tilting and panning onboard camera was unheard of in U.S. sports television."

As luck would have it, Squier was scheduled to travel to Australia two weeks later for a broadcast of "World's Strongest Man" with Arnold Schwarzenegger. There, he met with camera creators John Porter and Peter Larson to discuss their equipment, and he eventually convinced the pair to bring their technology to the United States and form Broadcast Sports International -- now the industry leader in remote camera operations for live sports, including all in-car cameras in NASCAR.

Convincing race teams to carry the camera proved difficult -- it added approximately 60 pounds to the car, and there were also concerns about what could happen if the camera came loose in a crash and became a projectile inside the cockpit -- but Squier was able to leverage his friendship with star driver Cale Yarborough into the camera being placed in Yarborough's car. Its coming out party would come in the 1983 and 1984 Daytona 500s, with the onboard camera picking up everything from Yarborough making racecar noises from behind the wheel to his dramatic last-lap passes to win the 500 in back-to-back years.

February 20th, 1983, Cale Yarborough won his 3rd Daytona 500.

— Andrew (@Basso488) December 31, 2023

The noise is Cale making engine noises.pic.twitter.com/Kbskf4pc1D

"Ken got that all to happen. Ken and Cale Yarborough, it was their friendship that resulted in that being in Cale's car," Joy said. "Because that was way bigger, heavier, and more involved than what had been in Benny's car in '79 which was just a fixed camera and a transmitter.

"You go to somebody today and say, 'Hey, I want to put a 60-pound lump in your racecar to maybe get you some better TV coverage' … You know that's not happening. But again, that was all Ken Squier and his forward thinking and knowing what a game-changer that would be."

Other concepts advanced by CBS Sports included speed shots from cameras nearly in the racing groove to give viewers a sense of speed, the first of which was a hand-operated camera at a hole in the catchfence near the exit of Turn 4. Operating the camera was heads-up work: Cameramen like Hermann Lang and Joe Sokota were required to wear helmets to protect themselves from debris, and they were given specific instructions to hit the deck and get out of dodge if a car came toward the wall where they were situated. Eventually, those shots were handled remotely through robotic cameras -- "I think to the insurance companies' delight," Joy remarked.

Interestingly, CBS Sports crews were interested in using an in-car heart monitor on a driver, but NASCAR denied permission to use such technology due to ethical concerns in the event of a serious or fatal accident. However, heart monitors have since become a feature of present-day NASCAR broadcasts.

Showing the moment, telling the story

As NASCAR's drivers became more famous and identifiable to the television audience, CBS' Daytona 500 broadcasts came to feature more intimate looks at racers throughout the field. For many years, this was done through pre-produced, in-race features profiling drivers throughout the field, whether it was Dale Earnhardt's roots in the mill town of Kannapolis, N.C. to J.D. McDuffie trying to make ends meet as an independent driver who owned his own cars. But as time went on, the humanity of the Daytona 500 would play out in real-time, and the real-time decisions of the CBS crew would make certain moments in the race's history outright unforgettable.

The most famous example came in the final laps of the 1993 race. Sensing that Ned Jarrett was becoming emotional watching his son Dale battle for the win, producer Bob Stenner watched as the second-generation Jarrett took the lead from Dale Earnhardt on the final lap. Then, as Jarrett led to the leaders to the back straightaway, Stenner hit the all-key to instruct the rest of the booth to stop talking, and for Ned Jarrett to drop his veil of objectivity and cheer his son to the finish line.

"Everybody lay out -- Alright Ned, be a Dad. Call your boy home."

"Ned's a wonderful guy ... It turned out to be a good decision at the moment, and it turned out to be great television," Stenner said. "It was just a spontaneous thing. I could hear it in his voice ... So, 'This is your son winning the 500, who better to bring him home than you?' And we even had a camera at the motorhome where his wife was watching. It was just something that was spontaneous and it worked out very well."

The elation of Jarrett watching his son take the checkered flag quickly became a case study in the magic of television, and another stroke of quick thinking would elevate another emotionally-charged moment five years later. When Dale Earnhardt finally won the Daytona 500 in 1998 after 20 years of trying, a massive line of crew members coming out to congratulate him was captured live thanks to associate director Jim Cornell, who sensed that something special was about to happen as producer Lance Barrow tried to get the broadcast to commercial break.

"We knew the whole Earnhardt story, we'd all lived it," Joy said. "So I think in the last couple of laps of that race, all of America was pulling for Dale, and of course he wins. Usually we set the finish order, shot of the winner, shot of the celebrating crew, 'We'll be back to go to Victory Lane' because it takes a car almost two minutes to go around there not at speed, plenty of time for commercial break.

"And it was Jim Cornell, our associate director who's in charge of getting us to commercial. Lance is going, 'Alright, let's get this to break.' And it was Jim who said, 'Wait a minute, don't go to break, don't go to break, there's something happening here.' And that's when that big receiving line formed up on pit road and we were there to capture that moment instead of having to play it back."

Those moments and more -- Bobby and Davey Allison's father-son 1-2 finish in 1988, Buddy Baker and Darrell Waltrip's breakthrough wins, Derrike Cope's massive upset in 1990 and multiple wins for Bill Elliott, Sterling Marlin and Jeff Gordon -- were all captured by CBS Sports until 2000, when the network gave way to Fox, NBC and Turner Sports in a new media rights deal. Nearly a quarter century after its last NASCAR broadcast, though, the impact CBS Sports had on the Daytona 500 and on NASCAR broadcasting in general is still felt today.

Ahead of this year's Daytona 500, much will be made of the lasting legacy and influence of Ken Squier, who died last November at the age of 88. But while Squier's impact is still felt -- from the term "The Great American Race" to the moments in time that will forever be associated with his voice -- so too are the contributions of other CBS personnel. Several members of the NASCAR on CBS crew, headlined by Joy in the broadcast booth, went on to continue their work through Fox Sports. Pilson, meanwhile, remained involved in the sport as a consultant for several years after the 2001 media deal began.

Above all, it can be argued that the heights that NASCAR has reached today are a residual after-effect of the 1979 Daytona 500, a seminal broadcast in the history of CBS Sports and one that sparked stock car racing's rise to national prominence and into the fabric of mainstream American sports culture.

"It was one of the great success stories of live sports television," Pilson said. "Lots of good things flowed from our live coverage of the Daytona 500."