Bobby Bonilla's increasingly infamous deferred compensation arrangement with the Mets is actually two separate deals totaling more than $40 million, not only the $30 million that has been previously reported, people familiar with the world's longest sports deal told CBSSports.com. Plus, a third 25-year Mets deferred compensation agreement, this one for former pitcher Bret Saberhagen, is also on the team's books, bringing the grand total to close to $50 million. Deferred, of course.

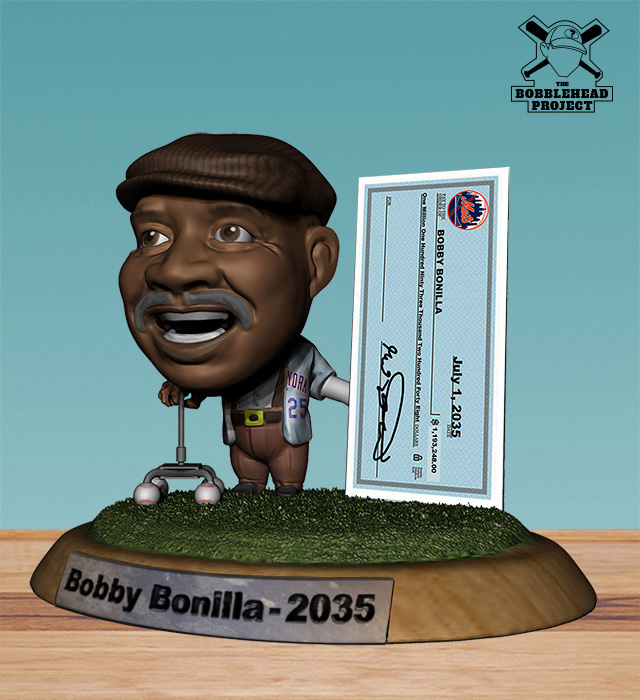

At a time the average MLB player salary has flown past $3 million (it's about $3.3 million), the Mets have pared their payroll to only a half-dozen million-dollar players, extremely low for a big-market team. It's noteworthy that the one payment that inspires the most fascination -- at least among Mets fans -- continues to be Bonilla's deferred payments.The Mets are celebrating their All-Star Game at Citi Field on Tuesday, but their perennial payroll All-Star continues to be Bonilla, who re-entered their books in 2004 and will stay on them through 2035, when he will be the best-paid 72-year-old ballplayer going.

The one previously known 25-year deferred plan that pays Bonilla $29.8 million in total becomes a semi-hot topic in New York every July (when the payments are due), but a review of documents turned up a second deferred deal for Bonilla, this one for $500,000 a year, also for 25 years, and beginning even earlier (in 2004). That brings Bonilla's grand total to more than $42 million. What's more, Bonilla isn't the only Met with such a deferred compensation deal, as Saberhagen's deal for $250,000 a year for 25 years also began in 2004.

Apparently, it actually was Saberhagen's deferred deal for $6.35 million total that provided a template for the subsequent Bonilla deals, one of which was done as his first $29 million, five-year Mets free-agent deal was winding down in disappointing fashion and the other when he came to the Mets a second time, hit .160 and feuded with manager Bobby Valentine and others. So considering his less-then-overwhelming stints with the Mets, it's not like the Mets exactly got their money's worth.

One piece of positive news for the Mets: The smaller arrangement, which is for $12.5 million ($500,000 a year for 25 years), is said by sources to be paid in part by the Orioles, who picked him up from the Mets and got stuck with him (and the contract). Word is, the Orioles are paying a bit less than half of that smaller payment plan.

As the Mets have pared their player payroll to about $90 million (counting current Mariners OF Jason Bay), down from about $140 milliona few years ago, Bonilla stands as the sixth highest-paid Met, at about $1.5 million this year while Saberhagen ranks as about the 13th highest-paid Met.

The Mets' biggest current payment for someone not currently playing for them, though, is the $21 million that goes to Bay, who was released by mutual agreement last winter before signing with Seattle.

As for the almost unending Bonilla plan, there actually are a few misconceptions about those payments; one is they didn't begin in 2011, and have actually been going on since way back in 2004. (Through multiple interviews and legwork, not by me but others, I've finally uncovered the real facts of the payment-plan story, which we'll get to shortly.)

But first: How did this become such a big deal again? And why is there such fascination over these payments?

A tweet by @AdamRubinESPN reminding us all that the $1.193 million check was paid July 1, as it is for 25 straight years beginning in 2011, inspired more than 2,000 retweets. Rubin modestly explained that he was simply "rehashing" old information about a payment schedule that had long-ago been made public. In any case, it inspired several posts and stories, including one recent in-depth piece in the New York Times regarding unending contracts -- featuring Bonilla's and one for former Islanders goalie Rick DiPietro.

Rubin's well-timed reminder about baseball's most famous delayed-payment deal triggered extensive response and more stories regarding the deal that put Bonilla on the Mets' payroll seemingly forver. The payments originally came about because the Mets were looking to defer Bonilla's $5.9 million salary, and Bonilla didn't hesitate to work out a deal.

"They came to us. It was their idea. But Bobby's always been a very conservative person," said former superagent Dennis Gilbert, working at the time with Beverly Hills Sports Council, the company he helped found.

The second one was negotiated also by BHSC, that time with partners Jeff Borris and Danny Horwits working out the arrangement with the Mets.

Part of the fascination resides in a presumed back story that the Mets deferred Bonilla's payments because they figured to make money on the deal with their investments through Bernie Madoff. Madoff, of course, since has been convicted as one of the biggest crooks in US history, but would earn Mets owner Fred Wilpon an estimated 12 percent to 18 percent a year. We now know that Madoff wasn't earning the Mets (or any of his other clients) anything because he was a Ponzi schemer.

Anyway, the Mets are said to have explained to Bonilla at the time that they wanted to use the money to pursue other players, which may have been the case, too.

The other part of the fascination regards the fact Bonilla is still in the upper quarter of the Mets' payroll at close to $1.5 million, counting the two payments, both made in July.

That could change next year, as current GM Sandy Alderson has suggested the Mets will spend more money on the free-agent market.

With so much interest in a decade-old deal in mind, here are a few more nuggets ascertained about Bonilla's famous deal:

• The first deal came about late in Bonilla's historic $29 million, five-year contract with the Mets in the early 1990s, not his second go-round in 1999 as has been reported. There was a year remaining at $5.9 million, and the Mets suggested deferring the money to free themselves up to spend it elsewhere. That is when Bonilla, represented by Beverly Hills Sports Council, and the Mets agreed on the 25-year payment plan for $500,000. (Note: Originally, I had that reversed here, but his first payments were for the lower amount, the second one is the higher one, nearly $1.2-million payment.)

• The payments from that arrangement started in 2004, after Bonilla turned 40 -- not 2011 as previously reported incorrectly -- and go through 2028.

• The second deferred deal for Bonilla with the Mets did come about in his second go-round with the team, and that is the even bigger deal. That is the one that's for precisely $1,193,248.20. That one goes from 2011 to 2035.

• The interest rate, unmentioned in all the stories, was precisely 8 percent, according to several people involved in the transaction. They all recalled, not surprisingly, that the 8 percent was arrived at through negotiation, with one recalling that Gilbert/Horwitz/Borris/Beverly Hills started at about 10 percent and the Mets first proposing about 6 percent. All parties recalled that interest rates were much higher back then and that 8 percent didn't seem out of line, though obviously now it seems high.

• The Mets also agreed to a deferred payment schedule with Beverly Hills client Bret Saberhagen, which has gone pretty well unmentioned in recent years. Saberhagen's payment is said to be for $250,000 a year for 25 years, making it $6.25 million total.

• The Beverly Hills partners tried to talk Yankees outfielder Danny Tartabull, who had signed a $25.5 million deal, into a deferred payment program for him with that team. But, "he wouldn't do it," recalled one person involved in those talks. That looks like a mistake now, as Tartabull -- known for very expensive tastes (he favored ultra-expensive wines and it was once suggested he never re-wore any of his designer shirts) -- recently was identified in news reports as one of the biggest deadbeat dads in Los Angeles. He owes $276,000 in payments to his two sons, according to police.