TEMPE, Ariz. -- Marion Grice crawls underneath his bed, sifts through about two-dozen shoe boxes and pulls out the one with the most pain and patent leather inside.

Arizona State's touchdown king places the Jordan XI "Breds," all black with red bottoms, on his unmade bed, a hint of sun from the apartment window exposing the box's dust.

Joshua Woods died because of shoes that looked just like these. The man Grice calls his brother bought the same pair at a Houston-area mall the morning of Dec. 21, 2012. Robbers followed Woods and a friend home, demanded the shoes and shot Woods as he tried to escape.

Grice has cried enough, which is why the shoes are no longer sobering reminders, but part of a plan.

"Eventually I'm going to frame the shoe in memory of my brother," Grice said. "I'm going to put them in my living room."

Those shoes, that frame and that living room could soon be located in an NFL city near you. Marion Grice is the nation's leading scorer with 18 touchdowns in eight games. The man Grice calls his brother hasn't been there to see any of the 18. But every time the reserved Grice flips the football to the back judge, Joshua Woods walks right alongside him.

Road to Tempe

Grice is sitting in the passenger seat of a rental car, fitting for a young man as well-traveled as he is.

He's been all over, or at least it feels that way to him. He has bounced from family to high school friends in Houston to an apartment near Blinn Junior College to today's destination -- a dark, three-bedroom apartment a few miles from the ASU campus with a Call of Duty poster on Grice's door. A picture of a man in a yellow-and-white uniform hangs from Grice's bedroom mirror. This is one of the first things Grice points out upon arrival, and is where his story begins. It's his father, Lester Grice, wearing the uniform of the Forest Brook Jaguars when he was a 5-foot-9 nose guard for the Houston high school.

Marion stayed with Lester after his parents separated when Marion was young, and learned respect from his father. Grice misses his dad's mac and cheese -- "He could cook anything," Grice says -- but most of all misses his dad. Lester Grice died of a heart aneurysm during Marion's sophomore year of high school. Marion's football story almost ended right here. Losing Lester made football feel like a chore, and he continued only due to the persistent urging of coaches and friends who recognized his talent.

Grice then lived with his mother but moved in with a high school friend for parts of his senior year at Chester Nimitz High. He didn't want to fall prey to temptation from neighborhood friends who welcomed trouble. Grice picked up misdemeanor assault and criminal mischief charges in 2008, when he was part of a group that fired paintball guns at bystanders from a moving truck.

Grice got himself a job as a grocery store bagger while trying to fulfill a goal of playing college football. Texas A&M wanted to sign Grice out of Nimitz, but an unfulfilled academic requirement left him scrambling. He accepted an offer from the only place that wanted him as a running back -- Blinn Junior College, a school about an hour west of Houston and best known as a one-time way station for Cam Newton.

Blinn prohibits students with felony or misdemeanor charges from living on campus, so Grice absorbed about $7,000 in student loans to pay his rent that first year. He still owes that money.

"I'm grown up," Grice says, reflecting on that period. "It was just one thing after another at that point. I've been through a lot. But I never wanted to show my frustration. I just kept quiet. I wanted to be positive."

Try positive yardage. Grice was one of the country's top-ranked junior college recruits after totaling 2,221 rushing yards and 33 scores in two seasons at Blinn, prompting newly minted Sun Devils coach Todd Graham to drive through severe Texas weather -- several tornadoes in the area that day, Graham recalls -- to meet Grice.

Graham remembers telling Grice: We want to put you in the best position to be successful.

That meant off the field, too.

"As special a kid as I've coached," Graham said.

Graham convinced Grice to sign with the Sun Devils. From a football standpoint, he'd found a very good landing spot at Arizona State. But the pain would follow.

'I have to go home'

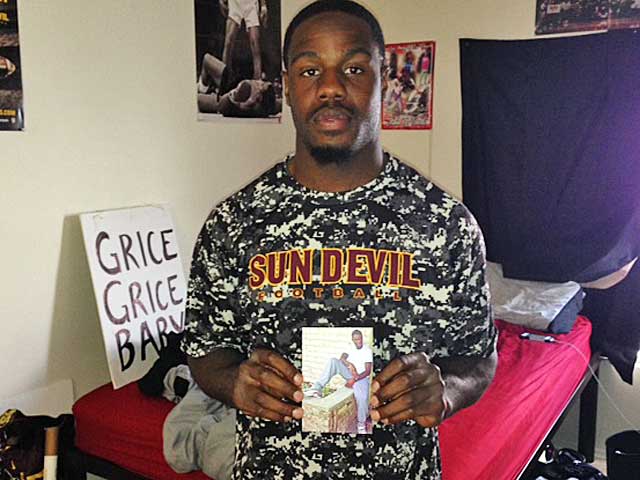

Wearing a camouflage Sun Devil Football shirt, Grice leans on his dresser, arms folded, focused eyes to the floor, preparing to tell the story of Josh.

Marion Grice and Joshua Woods called each other brother, though that isn't true in a strictly genetic sense. The two were born less than eight months apart. Grice said they have different parents. What is crystal clear, however, judging from the pain in Grice's eyes and words when he talks about Joshua Woods, is that Grice felt the familial bond of brotherhood, no matter what the DNA says. The two grew up together, lived together from time to time, and Grice called Woods' mother 'Mom.'

Grice talks about how Woods was trying to repair his life after trying to "grow up too fast." He dropped out of high school. He ran into legal troubles in 2008, including an aggravated assault charge. But Grice saw a different guy when he visited Houston on a bye week last October.

Woods was working two jobs and had just bought a Ford Taurus, the same car Grice has. He had learned from his mistakes, Grice thought, just as Marion had after the paintball incident.

During the trip home, the two walked a nearby bayou at midnight with flash lights. "We actually talked that night about, 'What would we do if we were to die?'" Grice said. "How much we would miss each other."

Grice would revisit that morbid conversation sooner than he ever could have thought.

Grice woke up around 8 a.m on Dec. 21, 2012. He felt uneasy, and the reason was Woods. Grice and Woods were both sneaker collectors, another commonality that had cemented their bond over the years. Grice remembered that Woods was picking up the Jordans on the first day of release -- they had texted about it a few days earlier -- and woke up wondering whether he should have reminded Josh about the danger of hitting the mall too early. Grice thought the malls were safer in the late afternoon, with more people around and more shops open. Early in the morning, the shoe store was the only place open, which worried Grice. He also knew Woods planned to buy several pairs of Breds at the Willowbrook Mall, reselling the extras to prospective buyers who had struck out on the limited edition. But a bigger purchase also meant a bigger score for robbers.

Grice called Woods' cell with no answer, then headed to the ASU facility to prepare for practice. Not long after, Woods' phone flashed the name of Woods' sister, Joshlyn, on the caller ID. She delivered the news. Grice's worries had been well-founded.

According to local news reports, a green four-door car had pulled alongside Woods' car, being driven by a friend, and demanded the Jordans. The friend exited the car and took off running, after which Woods moved from the passenger to the driver's seat to try to escape. He was shot in the forehead, and soon put on life support at an area hospital. In a time of family crisis, Grice turned to his ASU family.

"All I remember is telling the coaches over and over, 'I have to go home, I have to go home,'" Grice said. "I didn't know what to do."

Coaches remember the usually painfully reserved Grice, in a private moment, dropping to the ground.

Arizona State used emergency funds available to NCAA schools to arrange a flight for Grice back to Houston. Before he left Tempe, ASU players requested Grice come to the practice field so they could offer condolences, according to coaches. One after another, the Sun Devils did just that. The team prayed together.

"There wasn't much we could do for him," Graham said. "But we wanted to show him he had a family here."

Then-ASU director of football initiatives Horace Raymond, now on Oregon's staff, flew with Grice to Houston and drove him to the hospital. The two arrived shortly before Woods died.

"He doesn't show a lot of emotion -- you could tell he was trying to be strong for his family," said Raymond.

Inside, in addition to his grief, Grice was overwhelmed with guilt.

"At the time I felt responsible," Grice said. "I should have called as soon as I woke up to tell him not to go. I know now I can't blame myself."

From all accounts, this was little more than a senseless killing. After asking around while back in Houston, Grice believes the robbers had a scheme to target buyers carrying multiple bags of shoes. Three suspects have been charged with capital murder in connection with the case.

Tragedy into touchdowns

ASU's bowl game against Navy was eight days after Woods' death, which to Grice was perfect timing. The Sun Devils never pressured Grice into returning, but he wouldn't have needed any coaxing. Angry over Woods' murder, Grice was ready to hit something.

Grice carried the ball just 14 times against the Midshipmen, with his first big moment coming on a 10-yard touchdown run midway through the first quarter. After the score, he pointed the football to the sky. Offensive coordinator Mike Norvell waited for Grice at the sideline and met him with a hug.

"It was a special moment," Norvell said.

The TD made the score 14-0, and neither Grice nor the Sun Devils looked back. Grice turned those 14 carries into 159 yards, including another touchdown, in a 62-28 blowout.

"It was like watching Brett Favre after his father died," said ASU athletic director Steve Patterson, referring to Favre's 399 yards and four touchdowns on Monday Night Football, a day after the loss of his father.

"He was a beast," defensive tackle Will Sutton said of Grice.

The tragic event was a pivotal moment for Grice, a natural introvert who rarely talked to teammates. Toughness meant showing no emotion, he thought. After Woods' death, however, Grice realized his guilt would mushroom if he didn't talk to somebody. He eventually grew close with quarterback Taylor Kelly and former teammate Karl Holmes. He got more comfortable with Raymond and the coaching staff.

"I believe that was a turning point in his life," said Tim Cassidy, a senior associate AD for football who played a role in Graham signing Grice. "For a young man who had gone through so much, you could see his strength." The determination Grice showed against Navy has remained ever-present in 2013. The Sun Devils, at 6-2 and leading the Pac-12 South heading into Saturday's matchup with Utah, rarely reach the red zone without looking to Grice. With 18 scores, he's on pace to shatter Wilford 'Whizzer' White's single-season ASU record of 22 touchdowns, and also has a shot at Toby Gerhart's Pac-12 scoring mark of 172 points (Grice has 108, with as many as six games left on the schedule).

"I don't play for numbers, but it's nice to know all of this is paying off," Grice says.

Moving on

From inside that darkened apartment, Grice starts shaking his head. He admits he was familiar with one of the murder suspects, Kegan Arrington, who he says is the son of one of Grice's former pee wee football coaches. He didn't know Arrington personally, but he certainly knew his dad, who called to apologize shortly after the murder.

Grice remembers the man repeating, "I'm sorry. I'm sorry."

Your son made his own choices, Grice says he told Arrington's father. Don't feel guilt. Grice says he felt good about that conversation, which shows how far he has come mentally since the murder. You can tell how far he has come on the field by looking at some of the posters adorning his walls. There's a "Grice Grice Baby" sign made by an adoring Sun Devils fan, and a "Ready. Set. Conquer!" poster featuring Grice diving toward a pylon.

There's another poster, which sits just above his bed. It depicts Michael Jordan, and Grice considers the irony. He has idolized Jordan since he got his first pair of Air Jordans in the sixth grade.

If he ever meets Jordan, he'll ask about his, and Nike's, business practices. New Jordans are sold in limited supplies in some Houston areas, fueling a frenzy over obtaining the sneakers. Grice has seen people drop $200 they shouldn't spend for the prestige of owning the latest retro model. He has done that himself. Every time he earned $200 from that job bagging groceries at Kroger's, he headed straight to the mall.

Shoe stores hold raffles for the rights to purchase Jordan 'Breds,' which Grice believes causes anxiety and desperation in high-crime neighborhoods such as Greenspoint, the area of Houston where he grew up.

"I don't know why they don't have more available," Grice says of the shoes. "Around the holidays, people can't get them, so in my neighborhood, they'll do whatever they can."

Outside his apartment, two young neighbors holding skateboards approach Grice to offer encouragement for him and the Sun Devils.

Grice admits he's still not sure what to do with the attention touchdowns bring. Then he pauses, perhaps considering his ordeal and the plight of the shooters, who were not all that different in age from the kids on the skateboards.

"I want to be able to write a book and have people read it," Grice said. "I want to influence kids to be something in life. I just want people to know me, where if people think of Marion Grice, they speak positively."

The journey continues

Todd Graham was bouncing around Arizona State's practice facility, giddy over Grice's off-balance, one-handed touchdown grab against Washington.

In the lead-up to the game, apparently a Washington Huskies player had called Grice 'soft.' After Grice answered with three touchdowns and 195 yards, including the catch that inspired his head coach's ecstasy, being soft has its advantages.

"Did you see that?" Graham asks repeatedly. "You've got to see that."

Grice's scores satisfy Graham, but so do his reactions to the scores. He returns the ball to the official and quietly jogs off the field.

"He just finds a way to get it done -- never complains, never says anything," Graham said.

Grice went scoreless in last week's 55-21 romp over Washington State, but Norvell knows why: Grice garnered so much attention from the Cougars that everybody else scored instead. To observers both inside and outside the program, it would be hard to imagine Arizona State sitting here with a 6-2 record and a chance to win the Pac-12 without Grice.

It's not a happy ending, but it's a positive step forward for a player who has had enough heavy, negative episodes in his young life to deserve what qualifies as a respite.

Driving away from the ASU facility in that rental car, Grice reflects on what it took to get here, and talks about his motivation. What starts as small talk -- Grice's utter disdain for being tackled -- turns earnest when discussing his on-field mentality.

"I think about the past and I get angry,” Grice says. "You have to kill me to tackle me."