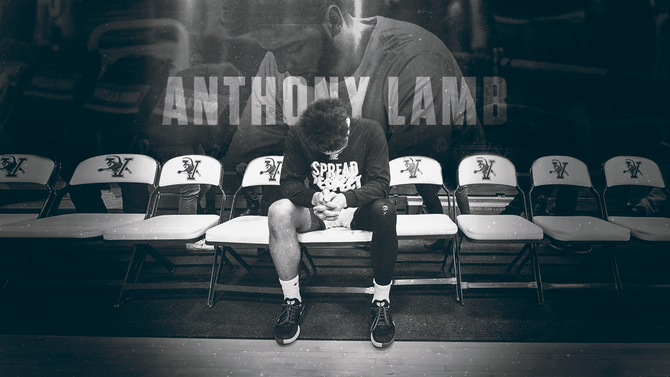

The fight of his life: Vermont's Anthony Lamb opens up about getting through darkness on his way to greatness

After battling mental health issues, Anthony Lamb is still in the room

The top of the Francis Scott Key Bridge in Washington, D.C., is approximately 185 feet above the surface of the Potomac River.

On Dec. 1, 2018, Anthony Lamb contemplated jumping off it.

Lamb and his Vermont basketball teammates had a two-day break between the second and third/final game of a tournament in the area. Idle time led to a dangerous, frenzied mind. That Saturday evening Lamb slipped out of the team hotel, into the D.C. night and wandered to the nearby historic bridge.

"That was probably the closest I ever got to dying," Lamb told CBS Sports. "I went for a walk and did feel like killing myself. That was my lowest point ever."

He paced, looking over the edge, into the river black. On the other side of him, cars whooshed every few seconds.

"I felt imaginary pressure," Lamb said. "A bunch of thoughts kept going and going. My thoughts got out of control about everything. I was so completely overwhelmed. I don't think I can make it. I don't want to struggle with this. Why am I even dealing with this? … I was completely down, completely lost and nobody knew. They couldn't find me."

They couldn't find me.

Lamb could have been speaking in a physical sense as much as an emotional one. He nudged away that suicidal urge. Still, this was newfound and terrifying territory. Lamb knew he was depressed, had been told he had signs of bipolar behavior. It had never been this bad.

"That was the scariest time for me," he said.

Lamb made it across the bridge and soon found himself on Georgetown's campus. The night air was cool, just above 40 degrees. Back at the team hotel, almost no one knew what was happening. Lamb's then-girlfriend contacted his best friend, Earl Brown, a UVM team manager. Lamb had put up a scare so much that it forced her to fear the worst. He exhibited foreboding behavior such as unfollows on social media and going hours without answering the phone. He would survive that night and has survived more than 450 nights since, but it has been at times as hard for him as it's been emotionally treacherous for his loved ones, coaches and teammates.

When Lamb eventually made his way back to the hotel late that night, he discovered Earl and one of his teammates rattled. Lamb was still out of it. To avoid full-blown panic, some with the team were not immediately made aware of what was happening. The next day, word found its way to Vermont coach John Becker.

"Earl tells the story and by the end of it he's crying hysterically, unconsolable over the thought of Anthony killing himself," Becker said. "I said, 'You can't do this. Look what it's done to Earl and look what it's done to all of us.' It freaked me out. And the way that Earl was uncontrollably crying, I knew this was very, very serious. That something close to this had happened, that got me emotional because I saw how emotional Earl was and then the pain Anthony was in to even contemplate it."

How does one care for a mind when that mind has a power to break faith with its owner? Lamb opened up to CBS Sports about his psyche, his motivations, unstable family history and ongoing aspirations for positive mental health.

"I go through thought wheels," Lamb said. "Dig into them and dig into them. Honestly, like, so my thing is, when it first happened it was: I don't have anything to prove myself to, so what am I doing? Life is pointless. There's no point for me to go through all this and put myself through all this stress. Why am I even alive? I questioned a lot of that. And it was: How do I deal with these thoughts and go through these things and handle them? I admittedly have had a lot of suicidal thoughts."

His testimony comes at a time when college basketball has seen an uptick in people voluntarily going on playing hiatus because of concern about their mental well-being. Some instances have been publicly disclosed, like Ohio State freshman D.J. Carton, a former top-40 prospect who stepped away mid-season.

CBS Sports has learned of nearly a dozen teams that -- in this and/or recent years -- have dealt with defections or near-defections due to mental health struggles. Everyone from star players to the last guy on the bench. A 2016 study conducted by researchers at Drexel University and Kean University found that nearly one out of every four Division I student-athletes show "clinically relevant" symptoms of depression.

Lamb is a rare example of an active star college athlete being willing to discuss his mental health and depression battles in an effort to better himself and ideally help others.

"I felt depression, I felt what it feels like to not be able to move, to be crippled by thoughts and emotions you have," Lamb said.

Thousands of college athletes could be dealing with demons similar to his. Lamb's story is a jagged one. He hopes it can become and remain a happy one, but the fact there is no ending is the best part: Anthony Lamb is still here.

"I've questioned my motives and what I want to do with my life and what life means to me," he said.

His fingers trace the table as he unspools some of what led him here. It's November of 2019, a year removed from his impromptu trip across the Key Bridge. On this night, the Vermont Catamounts have just pulled into New Haven, Connecticut, in advance of a big road game against Yale. In this moment, Lamb talks about how he's a stronger -- but still vulnerable -- person. Someone susceptible to mood swings and elements out of his control, though damn if he doesn't try to ensnare them every day. He is in good spirits but also contemplative.

Months after our initial interview for this story, Lamb will unexpectedly and for no specific reasons nosedive into another emotional valley.

"This was honestly my hardest year and I didn't know it was going to be like that as far as my mental health and the ups and downs I struggled with," Lamb said earlier this week. "I definitely have been all over."

Here in March things have steadied once more, he said. It's been pretty good for more than a month now. There are daily battles to wage, personal wars that have been won and lost, many of which only he knows about. Lamb is 22.

"I'm not as happy as when I play basketball, so is it basketball?" he wonders. "Do I have to play basketball to be happy? Is that what I have to do? I think it all connects back to how I grew up."

Though he didn't realize it for most of his young life, Lamb said since he got to college he realized that he probably long battled depression and has exhibited bipolar behavior, even if that diagnosis never came for him as he grew into one of the better players in college basketball.

"I don't even know if diagnosed is really the answer, I think it's more the process of learning and growing and mental health as a total, it affects your body, it affects everything," he says. "I've definitely had times where I've felt -- just based on my thoughts, not anything physical -- like I couldn't move. I felt immobilized. If that's what depression is, then yes, I've had that. I've had stints, weeks where I've struggled with it. It's not something that goes away."

How's Ant gonna be today?

He's a hell of a player, one of the best in college basketball. Now a senior and the reigning two-time America East Player of the Year, Lamb averages 16.6 points, 7.2 rebounds, 2.5 assists and 1.2 blocks. Vermont has never had a better pro prospect. A 6-foot-6 guard/forward, Lamb has cut weight, added muscle, improved defensively and holds a viable chance at being drafted. If that happens in June, he'd be the first America East player picked since Hartford's Vin Baker in 1993.

"I never really felt college was my last step," Lamb said. "College was the next step."

UVM has been one of the 10 winningest programs in men's college basketball since Lamb arrived in 2016-17. The Catamounts have lost five conference games in the last four years; only Gonzaga's been more dominant. Vermont has won 128 games and counting, the winningest four-year stretch in the history of the league. It's been a thrill ride with big bumps along the way.

Lamb was an outcast at first. Upon arriving the summer before his freshman season, he tested his teammates and not in the right ways.

"Freshman season nobody really liked me," he said.

He was relentless in the gym, so much so that he needed to be counseled long before people realized everything Lamb was carrying with him mentally and emotionally, even before he realized some of that baggage.

"My senior year of high school, we lost in the sectional championship and I was unbelievably pissed," he said. "I was, 'I'm so done with this.' I felt like a lot of it was completely on me because I was the best player. So my mindset going into college was: no matter what, we're not going to lose because I'm not good enough. That's never going to be the problem.'"

But that disconnected him from veteran teammates who understood the rhythms of a Division I season. All Lamb wanted to do was work on basketball and have his teammates match that desire every single day. He didn't drink and didn't want to play video games. He was on an island almost immediately.

"The minute he got here he was very intense," Becker said. "That summer before his freshman year, the guys would play and he'd get mad we weren't playing longer or more. He was in the gym all night and day and he was very intense and very vocal and wanted to be in charge right away."

He'd go from being the loudest guy in the gym, then a day later quiet and not engaging at all.

"He's always had this presence where it's like, he affects a group positively or negatively because he is such a strong personality and a really intense guy," Becker said.

How's Ant gonna be today?

Depression's heavy hand showed itself during Lamb's sophomore season. It was onset by injury; Lamb broke his foot the day after Christmas break during a practice. He was having a terrific season, and then Vermont went on to go 15-1 in league play without him.

"Any person would feel like: what's my value to this situation?" Becker said.

Lamb said the injury combined with other significant factors put him on a soul-searching path that threw him into an unending emotional and mental obstacle course. Lamb rehabbed like a maniac, got back in time to play for UVM in the America East Tournament, but believes he was 75% at best at that point. That was the year UMBC beat Vermont in a stunning last-second upset at UVM in the America East title game. It was the biggest win of UMBC's season -- until it played No. 1 overall seed Virginia six days later.

Lamb festered on the loss. He turned himself into a better player in the offseason, but the worst was yet to come. Seven months later, Lamb found himself looking down at the Potomac River on the Key Bridge. He is a man who needs challenges daily. He's someone who is motivated by being told what he won't or can't do. This can be as positive as it can be destructive. It is part of what's made him into one of the best college basketball players in the country.

"The problem is most of us view ourselves very differently than the world views us," Becker said. "I've been guilty of this myself, being way too hard, way too critical. So when he's having those days where he's beating himself up, I tried to tell him, 'That voice that's telling you those things, that's just not true. That voice is not right. What you're saying about yourself no one else thinks except you.'"

Becker and Lamb's relationship has evolved to a point that when there's a frequency disturbance, both know it. Anthony's been kicked out of practice and been pulled from games because of his attitude or non-responsiveness. In walkthroughs or pre-game meals, his mood can affect the entire team. He and Becker can now very quickly check in, find alignment and if long talks are needed, they're addressed that same day.

Vermont (25-7) won its fourth consecutive America East regular season title this season. Lamb has started every game in that run, foot injury notwithstanding. If the Cats win the America East Tournament this year, it will be the third time in four seasons UVM makes the NCAA Tournament. That would amount to the greatest four-year stretch in program history.

Lamb picked UVM over 36 other scholarship offers, making his choice the day after his official visit, his first and only one to any school. He grew into a Division I prospect by playing for the Albany City Rocks non-scholastic program. Lamb was 6 feet tall by the time he was 11 and was competing alongside 17-year-olds when he was 14. Hamlet Tibbs was involved with City Rocks prior to being hired at Vermont. Becker hiring Tibbs in 2014 was a catalyst to getting Lamb to UVM, a school and destination Lamb now says ultimately might have saved his life -- because it unquestionably changed it.

Vermont is one of the few schools to employ a full-time sports psychologist who is fully embedded with its men's basketball team. Ari Shapiro-Miller is a 37-year-old former college assistant who has a master of arts in clinical psychology. He's someone who six or seven years ago saw a need for mental health and psychology with student-athletes that wasn't being addressed. Becker initially brought him back as a consultant. Two years later the school committed to a mental-health action across all of its sports.

Shapiro-Miller now attends every Vermont practice and game and is available for the 400-plus student-athletes who play at UVM. For Lamb, the man is a crucial paternal figure and sounding board.

"Anthony is such an incredible young man, so bright, so insightful," Shapiro-Miller said. "As much as I hope I have helped him throughout the course of our relationship, he's given so much back to me."

For a long time, Shapiro-Miller and Becker were in effect Lamb's fathers on the ground at Vermont. As of late, he has been seeing another therapist outside the program as well. Vermont's conference, the America East, has also been crucial in allowing Lamb to feel less stigma about his issues. Dating back to 2016, it was a trailblazer as a league in this space. In November 2018, the America East became the first non-power-league to mandate that all of its universities "make mental health services and resources available to its student-athletes through the department of athletics and/or the institution's health services or counseling services department."

Three years ago former UVM basketball player Trae Bell-Haynes (like Lamb, a two-time America East Player of the Year) and former UVM swimmer Kelly Lennon started a "Rally Around Mental Health" program on campus that sparked a league-wide initiative.

"The league has been incredible supporting mental health," Shapiro-Miller said. "Trae Bell-Haynes was an enormous advocate for mental health. Without his support and the league catching onto his initiative, I don't think we'd be here."

Lamb cultivated his talent and grew a lot under Bell-Haynes' wing. They've become two of the most important players in the history of the school for reasons a lot bigger than basketball.

"I can openly talk about it here and not feel like anybody's judging me, because they could be going through the same thing," Lamb said. "I think the culture, first and foremost around me, has helped me with that."

Rachel Lamb knows cycles have to be severed and she's been working at that for 22 years. She grew up with the screaming, the beatings, the fist fights with her dad.

When she was 8 -- halfway in age to becoming pregnant with Anthony -- Rachel had her first encounter with suicide. Her alcoholic father and clinically depressed mother got into an argument. Dad was passed out from the liquor, so Mom swallowed a bottle of amitriptyline pills and went for a walk. She found a phone at a minimart and called friends from a nearby church. By the time they made it to her, Gail Lynch was almost unconscious. Her last words before the ambulance arrived were, "Tell my daughters I love them."

She died at the hospital shortly after 2 a.m. Rachel knows because she still has the death certificate. Rachel said her mother's death played a significant part in a destructive and careless adolescence. When Rachel and her sisters were teenagers, their dad sought to give them up for adoption. By 16 she was pregnant with Anthony and left the house when she refused to give up her son. She fled Florida and moved to Rochester, New York, to live with her aunt.

"My dad was there but he wasn't there because mentally he was a little crazy from the situation that happened with my mom," she said. "It's hard and I'm not perfect either. I didn't really get to grow up because I was broken-hearted from my mother and I didn't care if I lived or died. I tried to kill myself."

Anthony was 7 years old when he realized the dad he knew -- his stepdad, father to his younger brother Timothy -- was not his biological father.

"That was a, 'What?'" Lamb said. "'After that, 'OK, where's my dad? Why does my brother have a dad and I don't?' I can't really ask my mom that. How would a kid ask that question? Why? So my time was spent thinking about it."

A lot of time alone and avoiding conflict. He wouldn't prod. OK, so I don't have a dad. That's just how it has to be. And for almost the next 10 years, that's how it was. But when Lamb was in high school, his aunt Julie (Rachel's younger sister) decided it was time to try to find the dad. There was never confirmation over who Lamb's biological father was.

"I had a boyfriend at the time and a one-night stand with the other guy," Rachel said. "I was a little crazy at that time. I didn't care -- drinking, partying -- I didn't care if I lived or died. But I did remember the guy's name."

Nate.

Julie found him on Facebook. The photos were encouraging. Anthony looked like the man. Looked at his kids: Anthony looked like them, too. Rachel messaged him. She asked if he remembered her, remembered a night from 17 years ago. He did.

I want to tell you I'm pretty sure my son is your son. I don't need anything, but I thought you deserved to know.

Nate Larkins was in a relationship. His girlfriend found the messages and contact was cut off for more than a year. After Anthony committed to Vermont, Rachel reached out once more to apologize for any intrusion. Larkins was so relieved to have contact again; he had tried finding her to no success. His relationship with the woman had since ended, but she'd destroyed his phone and wiped out much of his data.

Larkins was not only wanting to meet his firstborn son, he was up for the DNA test to prove it was him. By this point, Lamb was a freshman at Vermont. The team had an early season tournament in Estero, Florida, just outside Fort Myers. Larkins lived in St. Petersburg, so Rachel flew to Florida, rented a car and drove two and a half hours each way to pick up Larkins and bring him to the hotel. It was after Vermont's win over Wofford on Nov. 21, 2017 -- a little more than a year before the bridge incident in Washington, D.C. -- that one of the biggest moments of Lamb's life, and his father's, materialized.

"That was … surreal," he said. "I forgot about it. I was in my room and it was like, shoot, this is NOW. It's now. I hesitated. I ignored the first call."

His mother remembers him not picking up.

"I'm sure the emotional aspect for Anthony was probably not that good," she said. "And in my brain, Oh shit, Anthony doesn't want to do this."

He was understandably somewhat ambivalent. How do you simply walk into a room and say hello to your dad for the first time after living for almost 19 years? Larkins was waiting in Rachel's room when Anthony walked in. They looked at each other, the nervous energy coaxing out big grins.

"It was weird, but honestly the crazy thing about it was he was so similar to me and my sense of humor, he was very funny to me," Lamb said. "I've never met this guy but why is he so similar to me, why does it feel so normal?"

He'd been waiting for normal for a very long time. When Rachel and Timothy's father/Anthony's stepfather separated, the man treated Anthony differently. He wasn't receiving much paternal love. For years Anthony was playing for, and sometimes in spite of, an invisible man. Now here he was, visible and before him in a Florida hotel room: 6-3, nearly 350 pounds and carrying an affable, thick southern accent.

"The hardest thing in my life was meeting him," Lamb said. "A kid that spends his whole life wanting to prove himself, whether it's to his dad or whatever, to prove that he's worth it to somebody that's not there. Somebody you can't reach, can't touch, can't hold. And then you meet that person, and it wasn't who you thought it was, but you meet that person and he's completely loving. He didn't know about me. I couldn't blame it on anybody."

Lamb had nowhere to place his hatred. He wouldn't and couldn't blame his mother. The space to feel anger vanished quickly and that left nowhere to put so many of his pent up emotions that he was really only recently coming to terms with. He felt joy, but there was still so much taken from him.

The DNA test came back 99.999% positive. Father and son talk frequently, and what's more: Anthony has visited the family in Florida and met all of his half-siblings. They look like him and carry similar mannerisms. Larkins has been caring and available but has not tried to intrude. He lets Anthony be in control of how much they are in contact. This has been a blessing but it has also compounded Lamb's identity crises at times. His desire for basketball and capability to dominate on the court had often been stoked by chasing a ghost. Where he once played for one, now he believes he plays for everyone.

"I'm still trying to figure out: why is it that I want to spend so much time playing basketball?" he said. "What really drives me is the thought that it's something I can tangibly prove myself in. Maybe not even basketball itself but the competition I can get better in, push myself in. That's what drives me, to prove my worth and making sure that everybody knows that I'm worth it. I don't have to convince myself, I have to convince everyone else."

As a boy Lamb lived in the heart of Rochester, New York, then briefly moved to an adjoining suburb, Greece, before needing to move back to the city, then finally back to Greece for good, about the time when Lamb was 8.

"When I was in the city-city, it was a bad area," Lamb said. "I don't remember being outside because she (mom) wouldn't let us go outside."

Lamb was a smart but quiet boy. Rachel would get calls from school about her son not cooperating because he didn't want to talk in class. He'd also avoid conflict, so much so that he once let a girl stick gum in his hair as a prank and refused to push back.

Lamb lived with his mother, younger half-brother Timothy and stepfather for nearly a decade, until Rachel and the man split. The boy was reclusive throughout much of his middle school and high school years. Unless it involved playing basketball, Lamb was largely antisocial.

"I would always joke around and would have fun with everything," Lamb said. "It wasn't like I had friends, though."

His house didn't have cable, so he'd watch the same movies over and over. He had a hoop in the driveway and would shoot, then do sprints after missed shots. Rachel would smile as she watched from the window. She worked as a nurse's assistant in geriatric care, and she worked a lot. After she split with Timothy's father, when Timothy would be at his dad's house, Anthony spent an inordinate amount of time by himself in those developmental years.

"That's a lot of my time that I remember being younger, just me being alone," he said.

He'd spend six-, eight-, 10-hour gaps by himself. The family was on food stamps throughout his upbringing. Stress and depression would cause him to snack a lot, a vice he still falls back on now.

"I never chose any of these problems or conflicts or to have these thoughts," Lamb said. "I was just a kid with no one really explaining anything to me, a victim of his own circumstance. All these complexes I had about not being good enough … you're good at basketball, I can push myself to do that. But I lost my reason to play basketball. I pushed myself for so long to play and try to get through that and prove myself to [my dad]. My mom loved me playing, so it made my mom happy and I could prove myself to my dad who wasn't there."

Rachel still lives in Greece. She has been to every single one of Anthony's home games and approximately 75% of the road games in his career. It's a six-hour drive each way from her house to Burlington, Vermont. She often drives back overnight -- 630 roundtrip miles in a day's time -- and gets home around 4:30 a.m. so she can work in the morning.

"When she's late to a game he's out of it," Becker said. "He has to see she got there safely. It's a big weight on him."

"I feel like it's my fault that he goes through that depression because it's genetics and my mom and everything," Rachel said. "I do find myself telling him a lot that I'm sorry that he feels that way and I wish I could change it. It is an emptiness and nobody could explain it unless they've gone through it themselves."

Rachel left geriatric care and the life of a nurse's assistant after 16 years because the stress of patients dying on her became too much. She's now a part of a union and works in carpentry, specializing in roofing, having just finished her apprenticeship. She's also been an Uber driver to help pay bills. She's put more than 300,000 miles on multiple cars in the past eight years as means to support Anthony's basketball dreams.

"All good miles, though," she said.

There are no certain environments that trigger the swoons or soars; that's the devil of the deal. The start of this senior season was tough for Lamb after an offseason that included going through the NBA predraft process in the spring. There were basketball goals to meet but yet again a gloominess settled in. The rhythm of the school year, some of the people around him, the whole college existence.

"What if I didn't get anything out of it, I'm going through all this stuff for what?" Lamb said. "What makes all of it worth it to me at the end of the day, regardless of how much money I make? Because that's not what I strive for. It's not money I find satisfaction in. Is it people, connections? It is that? Relationships? I get committed to relationships but then back out. I think that's probably a result of my childhood. Feeling like people are going to … leave."

He's never had a romantic relationship that lasted longer than five months. Lamb's a fascinating character study because he's a steady, highly reliable basketball player. He isn't volatile with his body or disrespectful to officials. Between the lines, when the game's going on, he is very much the man. Lamb dropped 30 points on Virginia earlier this season, the only player to do so against Tony Bennett's No. 1-ranked defense.

His teammates will vouch for his leadership ability. He is a giver, maybe even to a fault. Lamb faces double teams 40 times a game and is always willing to share the sugar, encouraging his teammates to take their best shots. Considering everything he's put into his college experience, and how he projects as a potential NBA player, it makes his journey all the more remarkable.

"There was a distinct point in time where it was like, life is not worth it," Lamb said. "There is no point in me going through with this. There's no point of it. Regardless of what the meaning of life is. I don't want to deal with it. There was a distinct part when it was -- this shit is not for me. I don't want any part of it. My sophomore year and parts of my junior year. I can say almost concretely, it's not like that anymore."

He's questioned his motivations and why he loves what he loves. He wants to be sure what he does now is for things he wants to do and so that he can be a better person for those around him. With each year he's seen and experienced up close just how much influence and sway he has over social groups. Time is up for "being caught by these complexes, these thoughts that make me feel like I'm not good enough."

As Becker said: 'If you're not playing well, your self worth is less than if you do play well. Neither are true." Lamb doesn't think about the bridge incident that much anymore. It was a desperate, lonely moment and he has never come truly that close since, but emotions can threaten to boil.

This is what weighs on Rachel.

"I think about my mom and pray to god, 'God, whatever you do give him strength that he don't end up like my mom because that right there would kill me," she said. "Losing your mom is one thing, but, if you told me I could have five more minutes with you or a lifetime with my mom, I would never do it. My kids mean everything to me. ... That coaching staff over there at Vermont, in a way they kind of saved Anthony's life throughout everything. Those coaches have been there for him in every way and I'm so grateful for them. I don't know how I could ever repay them."

Weekly meetings with Becker, Shapiro-Miller and his outside therapist have kept Lamb steady. Vermont's run through the America East has boosted him, as has living alongside the outrageously uplifting story of Josh Speidel, the UVM senior who has overcome a devastating car crash, coma and years of physical therapy to be one of the most uplifting stories in college athletics. Lamb and Speidel came into college together, walked such different paths right amongst each other for four years, and will graduate together in two months.

Becker and Lamb have also taken to going to Sunday morning mass together. They reconnect their bond through God, which has been another significant aspect of Lamb's ongoing retrieval of stability. The two can read each other on such a level where it's comfortable, even if confrontational, and always, always loving. It is a father-son dynamic to a healthy extent. Lamb is not the only one who's dealt with this at Vermont, not by a long shot. Becker has coached guys who have nearly stepped away from basketball because of mental health problems.

"What's always inspired me and what I've admired about Anthony is his commitment to this program," Becker said. "The essence of his work ethic since the day he got here. It's everything to him. He's put so much work into developing relationships with his teammates and his coaches and the community. It's incredible to see this kid work and accomplish things that people say he couldn't. It makes you want to work harder as a coach, makes you want to have to be on your toes that much more. He raises everyone's level.

"And then to have these shortcomings we all have or these demons and to really want to make changes and listen and want some guidance and want someone people to love him unconditionally, it's been, I just, he's like the culmination of a lot of different guys I've coached into one. He is Vermont basketball. He is the poster child of the care, the unselfishness, the drive, the talent. I never once felt he was ever going to leave here. And obviously he's probably been recruited hard every summer, but he's as loyal as they come. He's really a throwback. He just wants people that believe in him."

An entire fanbase and state already does and forever will. And now an untold amount of people will learn of Lamb's story and he'll soon discover he's more loved than ever. He wants people to know, most importantly, that though he has had struggles, talking about the tough stuff has been empowering. They are frightening experiences and hard words to read, let alone speak, but he is stronger because of them and willing to openly discuss them.

"Because of what my mom went through I can't give up on my life," Lamb said. "There's no escape that way. I have to find a way to continue to live this life and be at peace with it. The only way was to talk and get more help. By yourself you can only do so much."

He has won and will win again. Anthony Lamb is in the room and he commands your attention.