It was morning in Lithuania and Andrew Smith was getting dressed. As he put a shirt on, he caught an oddity in the mirror, a weird bump at the base of his neck just above the collarbone. The former Butler center was a newly married man playing foreign hoops in a faraway land, just three months into his first professional contract and living with his wife, Sam, and dog, Charlie.

Thinking little of it then -- Smith had battled mono and enlarged lymph nodes during his freshman year at Butler -- he brushed aside any serious concerns. Over the next two weeks, the bump got bigger and more uncomfortable. The scare increased when pressure crept on his insides, near his chest, and soon enough breathing became a conscious task. Lithuanian health care is not optimal, and the team physician spoke broken English, which did not translate at all to nuanced medical terminology.

Lithuania is a good basketball country. After making a run at the NBA, Smith turned down offers in Ukraine and Australia to play in the EuroCup, VTB and the Lithuanian League. The country offers among the best international competition basketball there is. But what began as an exciting overseas pro career was unraveling fast.

"There were a lot of broken promises," said Smith's wife, Sam. "Lithuania is very oppressed, not friendly and mistrusting. It's a place where, if you smile, some people think you're stealing from them."

In a foreign country with doctors they did not trust, the Smiths weren't getting clear answers. Tests were not immediately coming back with conclusive results. An initial biopsy came back negative for cancer, but still, Andrew reluctantly agreed to minor surgery because his neck's discomfort was preventing him from being able to play.

Smith was -- get this -- awake for the procedure and could faintly feel doctors tugging with metal tools at his numbed neck as they attempted to remove the blockage in his throat. What at first blatantly felt like the wrong decision turned into a mistake he was lucky to make. Without successful surgery, more evaluation was needed. Andrew's neck was coral-red as he and Sam spent their first Christmas together as man and wife. They Skyped home, telling their parents Andrew was cancer-free. But a few days later, Smith's growth got grotesque. He was living with a rock attached to his throat and a perma-red neck. He underwent a full body scan, and as they awaited the results, Andrew rung in 2014 feeling like his chest was shrinking by the day. He was unable to sleep.

Maybe it was his heart? No. For now, Andrew's heart was fine.

"I'm sitting over there, freaking out, and [the doctor] said, 'I don't know the words in English. I can't tell you,'" Sam said. "One team doctor was out of the country, and we were pretty sure she knew but didn't want to be the one to tell.'"

On Jan. 2, the general manager of the team insisted he meet the Smiths at their apartment with one of the team's doctors. The couple figured this was it. Cancer. Probably, anyway. The scan was showing a tumor near his lungs, separate from the blockage in his throat which had thankfully served as a warning sign. A blessing in disguise. So it was time to go home, to get a second opinion and immediate medical care in the United States. Andrew still had optimism that it was only an infection, that he'd be playing back in Lithuania in a few weeks.

Smith's team said they'd take care of the immediate travel arrangements. Instead, Sam was scheduled to fly out in mid-January, and Andrew, the sick one, was booked the week after that. This was not acceptable. The couple reached out to Andrew's parents, hastily booked flights via his father's frequent flier miles, and packed up their life in a day. On Jan. 4 -- 124 days after Andrew got to Lithuania -- he and Sam left their apartment in Klaipeda at 3 in the morning and drove more than 300 kilometers to the other side of the country in order to catch their plane out of Vilnius, the capital city.

Because of the quick turnaround and international regulations regarding flying with animals, Charlie had to temporarily be left behind. Andrew and Sam were clueless as to how often he was being cared for (they were told the general manager was the one walking and feeding the dog). It took Charlie three weeks to make it back to Indianapolis. By then, Andrew was facing a much scarier diagnosis. He knew he was gone from Lithuania for good.

It was a star-crossed start to 2014 for a man who would wind up lying dead on the carpeted floor of an office building seven months later.

***

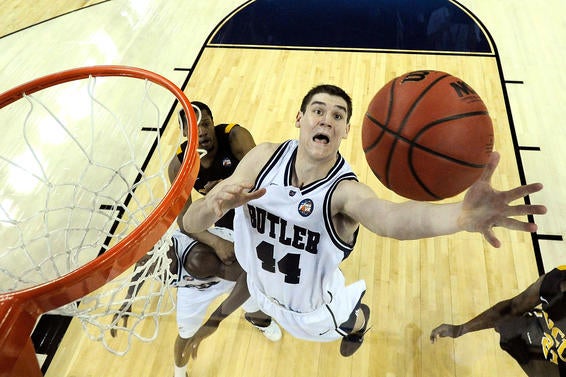

Andrew Smith came out of the womb at 24-and-one-quarter inches, the third of four children. The doctor in charge of his birth said he'd only seen one larger baby in his career of more than 3,000 deliveries. In four seasons at Butler, Smith played on both Cinderella Final Four teams. He helped the school to 110 wins and averaged better than 11 points per game. Pretty great for a guy who was initially only offered a walk-on spot before former Butler coach Brad Stevens and the coaching staff saw just how good he was.

"It blows your mind because he was such a mature kid already," Bulldogs assistant coach Terry Johnson said. It was Johnson who worked, tutored and guided Smith to become a better player, someone more than just a scout team big man -- and a second-team academic all-American.

Andrew grew up in Zionsville, Indiana, one mile away from Stevens' childhood home.

"His best games were against the biggest teams," Stevens said. "He went from a guy who was unsure about who he was as a basketball player to being a 'guy' guy, and that's a big leap."

In Smith's senior year he matched play with eventual No. 4 overall pick and rival in-state star Cody Zeller of Indiana. Butler won that game vs. the Hoosiers, who would go on to earn a No. 1 seed that season. That same year Smith held another future lottery pick in check, Gonzaga's Kelly Olynyk. The Bulldogs won that game too. And in the final win of his career, Smith hampered a third 2013 NBA draft selection, versatile big man Mike Muscala, to nine points in the NCAA Tournament. Smith was also a starter in one of the wildest NCAA Tournament games of the past decade, Butler's surreal 71-70 upset against No. 1 Pitt in the 2011 NCAAs. The win would spark the Bulldogs to a second straight national championship game appearance.

"Hey, Big Drew, what's going on!"

At first it didn't even register to Johnson that Smith, who should have been overseas, was calling from the States.

"I remember that call like the day of my boys' birth or the first time I met my wife," Johnson said. It was 90 minutes before Butler's home tip against Georgetown on Jan. 11, 2014. Johnson sat at his desk, his world at a halt, staring at the personnel sheet taped on the back of his clipboard.

"Basketball didn't matter to me the rest of that day. When he called, he couldn't get it out. Sam had to take the phone from him. He was really emotional. That was one time I didn't have a word for him, really. Throughout his whole career I had a word or phrase for him. I don't even think I said anything."

Like so many others, the last time Johnson had seen Smith was at his and Sam's wedding, in a spacious and rustic barn the previous spring. And now it was in a small and somber hospital room. Stevens was in the midst of a road trip in his first season as Boston Celtics coach when he got a call from Sam.

On Feb. 11, 2014, the day after the Celtics beat the Bucks 102-86, Stevens flew from Milwaukee to Chicago, then drove for three hours from O'Hare to Indianapolis to see Andrew. The big man was uplifted to see his coach but embarrassed to turn down an offer to go out to lunch. Really, the only thing he had a craving for -- the only things keeping the nausea, dehydration and headaches away -- were Gatorade and Gatorade protein drinks.

Two days later, a pallet with 480 quarts of Gatorade was delivered to the Smith home. The package read: "SMITH-CELTICS." A short time after that, another huge shipment, this one all protein drinks, was hauled to Andrew's parents' door.

Like all players, Smith needed to pass a physical when he began his career at Butler. His initial screening showed something that caused concern for the team doctor. Andrew's heart seemed too big. But after going for a separate and second evaluation, and getting more opinions -- including from the Indiana Pacers' cardiologist -- it was determined he was fine.

Andrew Smith didn't have an enlarged heart, doctors said. He had an athletic one.

***

The transatlantic flight was intolerable. Andrew's neck looked cartoonishly bad, his swollen lymph node wedged against his trachea. When they landed at O'Hare, they bookended their dizzying trip with another three-hour drive as they made speed to Indianapolis, keen on beating an incoming snowstorm. Members of both their families were worried and waiting at Andrew's parents' house when the drained couple arrived in the afternoon. The initial plan was to say hello, shower, decompress and put off another hospital trip for a few hours. It was immediately apparent this could not happen.

"You could tell he was sick, which is saying a lot," Ashly Stage, Sam's older sister, said. "Andrew is very resilient, not a complainer. He was struggling to walk."

Suddenly, the breathing took on a new form of scare: hyperventilation. They now believe, in retrospect, Andrew had a panic attack.

Andrew's situation was looking grimmer by the hour, so he was rushed to the ER at St. Vincent Indianapolis Hospital. Doctors looked at his neck, glanced at the tests from Lithuania and promptly deemed them useless. Andrew tolerated a new litany of tests. He was uncomfortable and frustrated. Could the guy just watch his football team, please? This was the night the Indianapolis Colts completed one of the greatest comebacks in playoff history, erasing a 28-point deficit to beat the Kansas City Chiefs 45-44.

What started as a brisk trip to the hospital would turn into an elongated stay that lasted two weeks. At the start of his treatment, Colts coach Chuck Pagano (who famously battled leukemia a season prior) called Andrew to wish him well. Teammates from Butler and current members of the team stopped in.

"We didn't want to say it out loud, but we figured he had cancer," Stage said.

Doctors initially determined Smith had non-Hodgkins lymphoma, which carries an optimistic 90-10 cure rate. Though a confirmation of the dreaded C word, this was good news, relatively speaking. Then, on Jan. 9, 2014, at 5 in the morning, Sam and Andrew squinted out of sleep to find a new doctor entering their room and delivering gloomier news before the sun even came up. While curable, Andrew's condition was much more serious than his team previously suspected.

"For me that was a moment there was a possibility he couldn't come back from it," Stage said. "For me it was a brief moment, and something I did not show my sister."

It was T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma, a rare, acute condition of non-Hodgkin's that gets 2,000 cases documented per year -- primarily in children. Immature white blood cells come out of the marrow, and when that happens they're vulnerable to mutating into a soft, cancerous mass. This coagulates around the heart and lungs, near the passageways. The cure rate for children is 50/50; for adults, it's a different story. Children's immune systems are stronger and more eager to fight back, to keep growing. To have the most successful results, Andrew's body would be soaked with a pediatric regimen of chemotherapy tailor-made to fit his uncommon height and weight: 6-feet-11, 240 pounds.

The first phase, called induction, brought the unpredictable: outpatient care featuring eight-hour spurts at the hospital with slow-drip chemos into his veins and spine; sleepless nights; bloody noses. But most unexpectedly, no more tumor. The vanishing came around Valentine's Day, and this signified the first bit of good news the Smiths received in months. Alison Lapsley began as Andrew's oncology nurse but is now one of their closest friends.

Lapsley stood with the doctor, the two of them staring at the scan and dumbfounded that Andrew's tumor had vanished.

"The doctor said it was completely unprecedented," Lapsley said. "That was huge and not anything anyone expected."

But cancer-capable cells can lie dormant, so consolidation (the second-worst phase) was necessary to smother them out. The week of the Sweet 16, they abruptly left at midnight to go to the ER. Andrew wouldn't return home for a month, forced to watch the final two weekends of UConn's charmed, unthinkable run to a national title from the sixth floor at St. Vincent. The bounce-backs that had been there in the previous nine weeks stopped. He dropped approximately 33 pounds, hitting his lightest weight since middle school.

"It's one that knocks you off your feet," Lapsley said of the chemo. "This regimen of chemo can't differentiate good cells and bad cells, so it kills the good and the bad. Emotionally, for Andrew, those were some of the hardest times because nobody wants to be in the hospital that long."

The nausea that was staved off finally came full bore, the chemo treatments long and sometimes thrice-a-day. He was injected via a port-a-cath, a device implanted under the skin of his chest that connects to a large, central vein in the body. This is how they kept Andrew's cancer in remission, flooding his body with medicines/chemicals that chased down submicroscopic cancer cells. He received Neupogen shots in his stomach to help with white blood cell recovery.

"I just didn't know if he was going to make it," Lapsley said.

Andrew would never complain.

"At that point the job situation was very up in the air too," Stage said. "Sam had put her job on hold to go and be with him in Lithuania. Sam is always a little bit more worried, tense and uptight. And then there's Andrew: Let's play some poker and watch some 'Seinfeld.'"

Sam watched this man, who was once her out-of-the-blue high school crush, sleeping, sweating and puking through the worst part of his life. Sam grew tired of reading, and as she put it in her occasionally updated blog that was chronicling this hellish spell, "Nothing on TV seemed funny anymore." She tried to exercise -- right next to Andrew. Nurses brought a treadmill to the hospital room. Sam thought that might help. No. With an immobilized husband beside her, the guilt from running was ever-existent.

But as Andrew broke through consolidation, the nausea stayed away long enough to allow the two to spend their May 18 one-year anniversary at her sister's downtown Indianapolis apartment. For eight months they lived with Andrew's parents. In the winter they had a plow man on call who'd be there even in the lightest snow conditions: Living at the end of a long, snaking driveway, they had to be able to rush to the hospital at a minute's notice.

Andrew finally had to shave his head in early July. Though he still had a number of chemo treatments left, and his body was still betraying him, he was feeling better. He couldn't play basketball but he wanted to work. Andrew graduated with an accounting degree, and he could put it to use. Craig and Lisa Roeder offered him a job with Mina Leasing and Financing, a company they own which is tied to a larger corporation they run, ProTrans. It was the Roeders who provided Andrew and Sam with their picturesque wedding in a converted barn.

It was the Roeders who would call Sam on July 31, 2014, and deliver the news.

It was Andrew's third day on the new job. Sam remembers now because it was the one time she forgot to tell him goodbye, to have a good day. But they did communicate. She sent off a text and then got a return message from Andrew in the early afternoon.

"Back at work! Love you tons."

***

1:43 p.m.: A startled Jennifer Smith hears a trash can kicked and then a body thud on the floor. Andrew Smith uncontrollably takes his chair down with him to the carpet. Jennifer stands up, peers over the top of her cubicle and asks, "Everything OK over there?"

No response. She hears sharp, labored, loud breathing.

"Almost if you, like, pinch your nose and try to breath through that," Jennifer Smith (no relation) said.

Jennifer walks around the cubicle and sees Andrew Smith's 6-foot-11 body unconscious, the whites of his eyes showing. Then his eyes close. Jennifer remembers her daughter's seizures. But this isn't a seizure. Andrew is going into cardiac arrest.

1:44: Jennifer and co-worker Kim Helvaty simultaneously call 911 and reach two dispatchers. Helvaty's call prompts an EMS crew, and her 911 conversation ends. But Jennifer's dispatcher stays on the line, is put on speakerphone and begins to assess the situation. Jennifer tells the dispatcher she can see vomit in Andrew's mouth. Jennifer's boss, Wendy Stevens, goes screaming through the hallways asking if anyone in the building knows CPR.

Dianna Mann, sitting at her desk in the southwest corner of the building, about 50 paces away from Andrew's body, hears Stevens.

1:45: Local police and EMS professionals from the Indianapolis International Airport and Wayne Township Fire Department Civilian Unit flare and blare toward the 40,000-square-foot building on 8311 West Perimeter Road, which sits adjacent to the airport. Approximately 40 yards inside ProTrans' headquarters, in the central hub of the office, Andrew has stopped breathing and his heart has stopped pumping. He is technically dead. Mann gets to Andrew and immediately begins administering CPR. A 5-foot-4 woman in her late 20s, she is the niece of Craig and Lisa Roeder. That Mann is even in the building signals providence: She studied for two years to be a surgical technician at Ivy Tech, then spent a year in the field only to then rejoin the family business.

1:46-1:48: Mann continues to perform CPR on Andrew's lifeless, supine body. A horde has gathered. Emergency crews are still in transit.

"I kept thinking, Where are they?" Jennifer Smith said.

Lisa Roeder calls Sam. Sam then calls Curt Smith, who is at work. He is nonplussed, does not trust himself to drive, and is taken to the hospital by his secretary.

1:49: Indianapolis Airport police officer Ian Spearman is the first uniformed responder. He begins breathing for Andrew while Mann continues to thrust at the chest.

"I knew when I arrived that this young man was gone," Spearman said. "I couldn't feel his pulse. The longer he went without one, the scarier it got."

1:52: Indianapolis Airport EMS squad 995, led by Lt. Johnny Russell, arrives on site. When they reach Andrew's body, Mann and the Spearman step aside. Russell tears off Andrew's blue-and-white-striped dress shirt and works his chest. EMT Mike Kiel places a bag valve mask over Andrew's mouth. Paramedic Todd McKinzie prepares the automated external defibrillator (AED), jelling two white round shock pads to Andrew's breasts. Andrew is shocked; his heart does not catch.

Aerial ladder truck 994 is barrelling across the airfield, lights and sirens blasting.

1:54: Wayne Township EMS and squad 994 arrive at the ProTrans building. As the crews get out of their vehicles, they're surprised to see they recognize each other. These separate units from different districts coincidentally trained together for the first time on this exact type of trial run -- a week ago.

1:55: Squad 994 winds its way through approximately 120 feet of office-space sprawl and reaches Andrew, who is shocked for a second time. Still dead. EMTs allot 30 minutes from when they first arrive to resuscitate a patient in cardiac arrest.

"It is a lethal arrhythmia," Shane Hardwick, EMS director of Wayne Township Fire Department, said. "Unless something is done to change it, you will die."

1:56: Wayne Township lead paramedic Ryan Ballard rolls his cot, backboard and crash kit through the front door. It takes him 15-20 seconds to reach Andrew's body. Not knowing where he's going, Ballard is guided through the office maze by a frightened trail of Andrew's co-workers, who've been rendered speechless.

"It was people experiencing something they'd never seen before," Ballard said. "They were pointing us in the right direction but they weren't saying anything. We've seen a lot, but the shock value with these people was something more intense."

Andrew's heart is in ventricular defibrillation, or "VF." When this happens, the brain swells and attempts to receive oxygen. Too much swelling and the stem of the brain will collapse, causing irreversible damage. Victims who go beyond five minutes in VF are at high risk to wind up brain-dead. At this point Andrew has more than doubled that, having been technically dead approximately 12 minutes.

1:58: Ballard intubates Andrew's trachea. EMT Kim Neal preps a 500cc IV bag and helps administer cardiac life support drugs through an 18-gauge needle, which also shoots Andrew with epinephrine (an adrenaline shot). The other trauma teams rotate CPR responsibilities.

2:00: Andrew is dripped with 300 milligrams of amiodarone (antiarrhythmic medication), then fails to come to life after a third shock. Sam and Andrew's mother, Debbie, are en route to the hospital.

"Every minute that passed, I knew his heart wasn't beating," Sam said.

2:03: Andrew has been technically dead for 20 minutes. If he can even be brought back at this point, life as a vegetable is the overwhelming odds-on scenario. Curt Smith sobbed over the phone, unable to fully get through recalling the day his son collapsed. He spent all of 2014 wondering if and when his son would die.

"I'm sorry," he said.

2:04: At this point in the crisis, between Mann and the EMTs, Andrew's chest has been pumped more than 2,000 times.

2:05-2:06: Andrew is rolled and then strapped to a backboard, lifted up on the gurney and prepped to be brought to the ambulance. Russell is standing next to Andrew, about to compress his chest again when McKinzie yells for everyone to "CLEAR THE PATIENT!" The AED monitor has given approval for one more shock. Andrew is given a 150 milligram dose of amiodarone and jolted for a fourth time.

This is when Andrew Smith's large, athletic heart beats for the first time in more than 22 minutes. He is alive.

2:07: Andrew experiences agonal respiration, a last-resort effort the body makes to restart itself. Death is still in the room. His lanky frame puts the pit of his knees at the edge of the gurney.

"We were thinking, 'Who is this dude?'" Ballard said. "Also, sometimes slow is fast. The faster you go, the sloppier you can get. In this case, it was: We've done the legwork, now we need to sustain. Let's be easy. Let's make sure we're not pulling any tubes or IVs out. Let's not ruin this."

2:11: As Andrew is loaded to leave, the crews discuss which hospital is closest. It is IU Health West, which is five miles out. As Medic 83's ambulance zooms, mucus and vomit are removed via French catheter, and Andrew is instinctively clamping his teeth on the tube burrowing 23 centimeters into his body. But his blood pressure is a tremendous 120/90. His pulse is at 76 beats per minute, and as they get closer to the ER, Andrew is taking 14 breaths -- his own breaths -- every 60 seconds.

"I was messed up because I had never lost anyone," Spearman said. "I went home and cried."

2:26: The ambulance arrives at IU Health West, where Sam and Debbie have been waiting for 10 minutes. Curt Smith arrives 10 minutes after Andrew.

"We're in the ER, and it doesn't look good," Curt said. "But his eyes are open and we can tell he's there. It's Andrew. It's not like he's gone."

"At first I didn't think I could be close to him because they were aggressively working on him," Sam said. "He reacted to me, bucking his chest. A tube was in his throat. You could tell he was uncomfortable."

Andrew's heart, which didn't work a half-hour prior, was racing out of control.

***

The overwhelming majority of people who go into VF do not survive, according to national statistics. Of those who do and are put into a coma, only 2 percent patients of walk of out the hospital with zero physical or neurological effects.

When it comes to acute lymphoblastic lymphoma patients who lie dead for 22 minutes due to heart failure, there is not a data pool for survival rate.

After storming into the ER, Andrew was induced into a hypothermic coma, his body gloved in a padded, temperature-controlling device suit called Arctic Sun, which dropped his core temperature to 80 degrees. His ICU room was kept quiet and dark. Overstimulation could lead his brain to collapse on itself. Sam would shiver in the 50-degree room, and there was one moment where she thought: I'm about to lose it. I need everyone out now. On two occasions she forced herself to leave because her emotions were overtaking the situation.

"You just never want to imagine, let alone have the conversations, 'We're worried your husband's going to go brain-dead. We think he's going to be a vegetable when he comes out,'" Sam said. "That was the first day. That was one of the lower points. I was preparing myself for him not to be 'Andrew' anymore. … I was at a breaking point."

Lapsley feared Andrew was done. She couldn't bring herself to tell Sam.

"I know God can work miracles, but I'd never seen one happen before, and I had a bleak picture of what was going to happen with him," Lapsley said. "I really did think that was it. I thought, How did we go through everything with the cancer, the chemotherapy? What was that for? Now he's going to be brain-dead?"

Stevens was in northern Indiana when he heard. He was brought to tears when he visited Andrew's comatose body on Aug. 2. Terry Johnson heard the news while at a Skyline Chili on vacation with his family. They debated going home but Sam said no.

"It … it's got me speechless even talking about this right now," Johnson said.

The turn came in a private moment that Ashly accidentally happened to witness. Even Sam wasn't aware of it despite being right next to her husband.

"It was a very, very bad night. A dark night," Stage said. "He was sedated both in mind and muscle. They made it so he was unable to move. I remember walking into the hospital room, and Sam was really upset. Sam is very strong and doesn't show that part of herself to many people, but I saw her crying. She went from leaning on his chest, and I saw him move, as if to comfort her, though he was medically sedated in every way. I saw it, and it defied anything. He shouldn't even be able to move. You could see on the heart monitor he was responding to her being upset. It should not have happened."

On Sunday, Aug. 3, 2014, Andrew came out of his coma. Toes wiggling, fingers bending, eyes blinking, legs moving, arms lifting. Heart beating. Mouth opening: soft, but intelligible speech. It's Andrew. Sam keeps the specifics of those first few hours private, but she did say they were "some were the most significant, intimate moments. Him coming out of the coma, I've never experienced something like that."

"It's miraculous," Stevens said. "It's an absolute miracle. There is no other way to interpret this. They've been through more in a 20-month marriage than a lot of people go through in the first 20 years. I was amazed. He amazes me every time I talk to him. When he got to Butler he was a really bright guy trying to find his way playing basketball. He became one of the most confident, toughest, hardest-working players I've ever coached. And Sam is an absolute rock."

Though doctors would not officially link the two, Sam and Curt Smith believe the cancer is what caused Andrew's collapse and visit with death. The primary doctor told the family Andrew's recovery was the best of any he'd ever seen.

"In my mind, this is a true, certifiable miracle," Sam said. "I've always had a peace about this because I know who the author of life is and I know he is good. Now that I've seen him fight cancer and seen him fight this amazing heart incident, I'm all the more confident he's going to be fine and make it. There's some reason he's alive today. I don't know what it is, and maybe he doesn't know what it is, but it matters."

To prevent flashbacks, stress disorders and the threat of eternal personal nightmares, people who experience what Andrew experienced are given drugs to wipe out part of their memory. July 31, 2014, is a blackness in his head. The last thing Andrew can vaguely remember is leaving the Roeders house after dogsitting the night before. He has no memory of coming to, only a foggy vision of sitting in the hospital. Ballard and the teams that saved him -- who were honored and finally met Andrew just two weeks ago -- visited him in the hospital.

"He looked awestruck then," Ballard said. "Like nothing happened. 'What are you guys doing here?' You just don't get someone to come back 100 percent. Usually the great people don't have the best outcome."

Hardwick agreed: "These are the ones you don't get back; this was a great save. We made a difference in someone who's going to go on and live a productive, meaningful life."

"I thought he was gone," Spearman said. "The next morning, they said he was alive and I didn't believe it."

Russell put simply: "Obviously it wasn't his time to go."

When the Roeders stopped by his room, Andrew joked, "You're probably going to have to retrain me." The fact Andrew left the hospital with full control of his faculties barely a week later -- and has not suffered any setbacks -- is supernatural.

On Dec. 5, after facing another three months of chemo, dozens of transfusions and having to finish the hard way because of an infected port-a-cath, Andrew took his final treatment. More than half his nights in 2014 were spent in a hospital. Andrew is now in maintenance, the third and final phase of the cancer battle. It's one you never really finish. He'll be on close watch for at least another year and a half before being cleared and will require medical care for the rest of his life. He lives with a defibrillator in the left side of chest. He hasn't regained all his strength yet, can barely dunk, and still struggles to move quickly.

Since the new year, he's taken four trips to the doctor. He battles nausea almost every morning and requires six to seven pills per day. But Andrew and Sam have moved past the fear of having conversations regarding children and finances and long life. He's back at ProTrans. He's making a living. Two weeks ago, Sam and Andrew bought a three-bedroom house in the historic district on Indianapolis' Eastside. When they're not painting their nights away, the couple catches up on "House of Cards," "Mad Men" and how about this one: "The Walking Dead." They also got to Hinkle Fieldhouse plenty this season, watching Butler play its way to another NCAA Tournament. Andrew also just got back into basketball by coaching in a 20-team youth league that blends his love for faith and hoops.

"I'm not on this earth to go out and play basketball games. I'm on this earth to share a story people can hear," Andrew said. "Before this, I was born [to a] Christian family, went to Butler, a Christian school. There were never any tests. I've kind of felt like this was my answer to my prayer even if it's obviously not what I wanted. Our faith gives everything that happened last year a purpose. … If I was going to bring one person back from a dark place, and we've had hundreds and hundreds of letters, then this entire year was worth it."

If Dianna Mann chooses to commit her life as a surgical technician, if she does not ask to rejoin the family business, if she is not in the building that day, Andrew Smith most likely dies at 23.

"I believe God puts us in a certain place at a certain time and for a specific reason," Mann said. "Maybe I did go [to Ivy Tech] for that and for that reason. I don't feel like he owes me anything. … It didn't cross my mind at the time, but afterward I wondered if he'd make it. That doubt was there in the back of my mind, wondering if you could do everything you could."

Last Tuesday Mann was called to the ProTrans reception desk. The Indianapolis Airport Fire Department presented the hero with a plaque and medal. It was then, 215 days after she heard Wendy Stevens screaming down a hallway, that Andrew Smith met Dianna Mann for the first time.

Mann is so humble her parents didn't even know what she did until Craig Roeder told them at a family gathering. She didn't seek a reunion sooner with Andrew because she didn't want to be another person around, another person asking more questions. Mann wanted to grant him peace. She helped saved his life, and even though Andrew can't remember that day, for as long as he lives he'll never forget it.