|

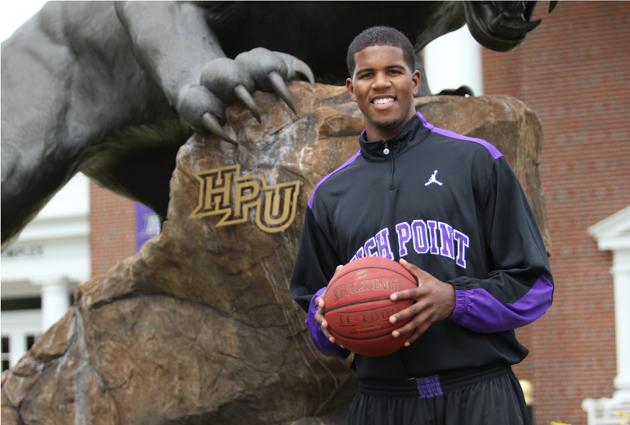

| High Point forward Allan Chaney will play his first game in 1,346 days on Friday night. (Provided to CBSSports.com) |

HIGH POINT, N.C. -- Allan Chaney remembers it all. The two brushes with death, the countless hospital visits, surgery eight months ago when doctors literally cracked open his chest -- and, most vividly, the conversation with the doctor from Boston who was part of the esteemed Dream Team of cardiologists.

"He told me I'd never play again," Chaney said.

However, Chaney will make his long-awaited return to the court on Friday night, exactly 1,346 days after his last college appearance. He doesn't even recall that three-minute, mop-up duty stint on March 4, 2009, at Humphrey Coliseum in Starkville, Miss., since he was too upset about going from a productive freshman early in the season at Florida to a guy who didn't get off the bench in 11 of his final 12 games in Gainesville. The 6-foot-9 Chaney was a disgruntled 18-year-old kid back then, upset with his lack of playing time for Billy Donovan. Now he can't stop smiling, having overcome numerous setbacks -- including that one when Dr. Mark Estes informed him his basketball career was history.

| College Basketball Season Preview |

| Related links |

Chaney won't make his comeback Friday night in front of a packed house in Gainesville but instead on the plush campus at High Point University, the school that took a chance on Chaney after many weren't willing to take the risk given his medical history. Chaney's return will come at the Millis Center, in front of a couple of thousand fans who will watch him make an improbable return to college basketball against UNC Greensboro in a nonconference tilt that won't even be a blip on the national college basketball radar.

But for Chaney, it's of no consequence where he's playing. It just matters that he is back out on the court.

"He just wanted a chance," said Chaney's mother, Brenda Pledger.

The date was April 24, 2010. Chaney was at Virginia Tech in Blacksburg, Va., where he opted to play after he became disenchanted with his situation at Florida. It was a normal offseason individual workout after Chaney had sat out the previous campaign due to transfer regulations.

"I got through the whole workout perfectly fine," Chaney said. "It was my best shooting day. All of the sudden, I go to the free throw line, do my routine and I'm huffing and puffing. I took a deep breathe, and I couldn't catch it. Then I threw the ball at the rim and had to sit down. All I remember is waking up. I fell over and was out for 30 seconds."

"I didn't know what to think," he added.

Chaney went to the hospital, his first of seemingly endless visits. The initial thought was dehydration. However, eventually Chaney was diagnosed with viral myrocarditis, a potentially fatal infection of the heart that causes inflammation.

"It wasn't anything I was born with," Chaney said. "I'd been fine my whole life. Until that day."

The tests kept coming. Doctors at the University of Virginia still believed it was just a virus that would go away. In the meantime, Chaney wasn't allowed to do anything -- no running, no workouts, no shooting. Chaney eventually returned home to Baltimore -- frustrations mounting. There were no lingering effects. In his mind, Chaney was 100 percent -- and persuaded a friend of his to go to the neighborhood YMCA on Aug. 22, 2010.

"I got a phone call," Pledger recalled. "I told him he needed to rest, but he was tempted. He was in denial, but that second episode made a believer out of him."

Chaney had been the recipient of an alley-oop and was jogging back down the court. The next thing he remembers was his vision becoming completely blurred. That's when he fell to the floor and passed out. Again.

"That's when I realized something was wrong with me," he added. "At that time, I knew I couldn't play."

But Chaney never lost hope that he'd get back on the court -- even after he flew to Boston and met with Estes, cardiologist of the famed 12-member Dream Team put together to consult on the status of former Boston Celtics star Reggie Lewis -- who later died of a heart defect in an off-season practice in 1993.

"He looked right in my eyes and said that he didn't think I'd ever play again," Chaney said. "And he was so confident."

But Chaney got a second opinion from cardiologist Dr. Francis Marchlinski at the University of Pennsylvania.

"He told me, 'I can get you back to playing.'"

Marchlinski then explained the only way it would be possible was with a defibrillator, a device that monitors the heart and is utilized as a precaution in case heart issues arise. Chaney was immediately skeptical, wondering how he'd be able to play with a something that would have wires hanging from it. Then Marchlinski informed him of a new, innovative wireless device still in the experimental stages that wouldn't restrict his movement while on the court.

"I was feeling this guy," Chaney said of his new doctor.

Pledger was worried -- as all mothers would be about their son playing basketball following a pair of near-death experiences. She scoured the Internet and found examples of other athletes using defibrillators. The next step was to examine the heart's electric function (EP study), then a stress test. It was June 2011 when Chaney finally got the approval for his new device. The wireless defibrillator was installed on Nov. 7, 2011, and was followed by a three-week recovery period.

Chaney thought he was in the clear and was ready to move onto the next step, figuring out where he'd be able to continue his college career. However, Marchlinski told him, following another stress test, that he wanted to crack Chaney's chest open and perform another procedure after doctors were able to induce irregular heartbeats.

"He'd been right from the jump," Chaney said. "So I was OK with whatever he said. Let's get this done, and then we'll be through with it."

Marchlinski was hopeful he wouldn't have to crack Chaney's entire chest open, but the recovery was slated to be anywhere from three to six months depending on the extent of the surgery. It was now March 8, 2012, when Chaney returned to the University of Pennsylvania.

"It was like open-heart surgery," Pledger said. "To see my 6-foot-9 son on a stretcher with all these machines hooked up was really hard for me. He handled it well and was pretty brave, but the doctor said he got a little scared when he took him back to the room."

A few hours later, Chaney woke up, looked at his mother in the recovery room and freaked out -- trying to rip the tube out of his throat. He was visibly upset. But once he calmed down, Chaney received the news that the surgery had gone well and his recovery time was in the three-month range.

"It was the best news ever," he said.

Chaney was cleared on May 18 and then was put in contact with Sesoo Ikpah, a guard at American International College who played all of last season with the identical defibrillator that Chaney was given. The pair worked out together in Las Vegas while Chaney waited to see if any schools could get him cleared to play again.

"I haven't had any issues," Ikpah told CBSSports.com about playing with the device. "Honestly, I don't even know it's there anymore."

It wasn't easy for Chaney to find a taker, though -- as many schools won't take a risk on a heart situation. Virginia Tech made it clear long before that they wouldn't clear him. La Salle and Temple called, and UAB inquired. There were plenty of coaches who were interested, and Chaney was willing to sign a waiver. But there just weren't many administrations that would sign off on bringing Chaney on board.

High Point assistant Ahmad Dorsett had Baltimore connections and called Chaney. The doctors at High Point were optimistic. The next thing that Chaney knew, he was on an official visit to the school, where he met with team physicians, consulted with a local cardiologist and was ultimately cleared to play for the Panthers.

"It moved quick," High Point coach Scott Cherry said. "I was amazed."

"Why would I turn it down?" Chaney said. "I had no idea if anyone else would clear me. I came here and love it."

Chaney has already shown flashes of the player who was once a heralded recruit coming out of New London High in Connecticut and once called his best player by Virginia Tech coach Seth Greenberg. The first time that Chaney touched the ball in an intrasquad scrimmage, he exploded and dunked over a teammate. He then scored 16 points and grabbed six rebounds in an exhibition game against Mars Hill on Saturday night.

"I was nervous," Chaney admitted.

Chaney won't stop smiling nowadays. He has been literally given a new lease on life, both on and off the basketball court. The redshirt senior was granted a sixth year of eligibility so that he can play this season and next year as well -- due to his medical hardships. It has been nearly three years since he took the court -- and now he'll become the lone D-I men's basketball player to compete with a defibrillator.

"That doctor said I'd never play again," Chaney said. "Now look at me. I'm playing. I don't know how far I can go, but I'm looking to go far."