March makes believers of us all. The NCAA Tournament is more than 75 years old, yet every year it gives us something we've never seen before. The charm of the bracket lies in how we always allow ourselves to be shocked even when we know the shock is coming -- it's just a matter of who and when. For decades, those flares of surprise were contained to the corners of a few opening-weekend thrillers. Double-digit seeds dramatically cutting down aristocrats.

In the modern tournament era (since 1985, when the field expanded to 64 teams) late March and early April were only available on the calendar to the sport's richest and biggest. Villanova, a bona fide Big East power with a future top-10 pick, was seeded eighth but became national champs in '85. LSU, a founding program of the SEC, was an 11 seed that broke through to the national semifinals a year after Nova. Four years after that, UNLV won a national title behind a Hall of Fame coach and one of the most talented, intimidating starting fives in college basketball history. There was nothing about Vegas that was synonymous with mid-major. These were the teams regarded as Final Four long shots.

As college basketball stylistically transformed through many eras and into a new century, a constant rule remained: Mid-major teams did not win four games in the NCAA Tournament.

Until 2006, of course, when a commuter school out of Fairfax, Va., burned down the country's brackets, not to mention sport's precedents. George Mason became one of the best stories in America that year. The Patriots' Final Four run remains one of the most unexpected, groundbreaking achievements in college hoops history.

Before Butler. Before VCU. Before Wichita State. Before all of them, there was George Mason. Those other programs had proud histories and some tournament success in years before their Final Four runs. But Mason, which barely made the field in 2006, truly came out of nowhere when it cracked the dam. The school had three tourney bids in its history -- and had never even won a game.

George Mason. A college named after a man who defied convention and redefined the Constitution when he fathered the Bill of Rights. The Patriots defied convention and redefined the rules of the tournament when they defeated three legendary programs and provided the greatest upset in Elite Eight history.

"I got chillbumps on me right now even talking about this," James Johnson, an assistant on that team, said. "Absolute joy. Still to this day."

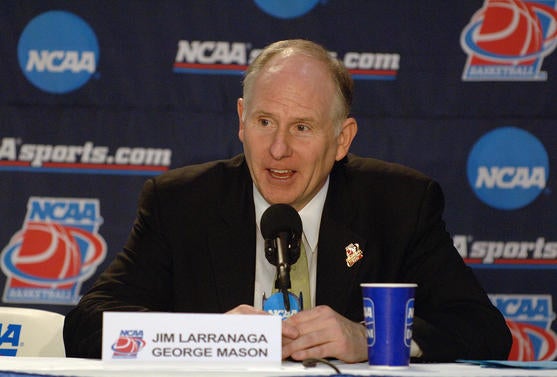

Everyone remembers the epic vs. UConn, the shot that didn't go in and Jim Larranaga, the fun-loving coach who inspired his team to one of the most unforgettable tournament trips ever. But there is a deeper story to Mason's glory. Many don't realize that team dealt with death, physical altercations and suspensions. A couple of events almost prevented Mason from being in position to make the tournament. The fact it dodged those obstacles makes that run even better. This is the story of college basketball's first true Final Four Cinderella.

DEATH AND WICHITA STATE 1.0

The BracketBuster era was fully fledged in 2006. The mid-February, made-for-TV tilts gave quality mid-major teams a chance to earn credible non-conference wins. Larranaga asked for the toughest possible opponent. He was awarded a road game vs. Wichita State. Tony Skinn and Folarin Campbell were originally not supposed to play in that game -- for very different reasons.

The name "Folarin" means "walk with glory" in the African language of Yoruba. When he was born on Feb. 27, 1986, it wasn't Campbell's parents who named him. It was his grandmother, Christina. In late January of '06, Christina Campbell died at the age of 72 in her home city of Lagos, Nigeria. Campbell met Larranaga at his office and told him the news, then said he wanted to attend her funeral.

Which would be held in Nigeria. In February.

He'd be gone two weeks.

"My heart jumped into my mouth," Larranaga said. "He asks for permission to attend the funeral. It's an extremely close family. What do I say to this request?"

The news came shortly after Mason discovered it was heading to Wichita State on Feb. 18. Larranaga was torn. The Campbell family was so generous, so loving. They attended every GMU home game. He knew if Folarin left, Mason's chances of beating Wichita State would leave with him on that plane to Africa.

The coaching staff was invited to the Campbell family home in Silver Spring, Md., to hash out the dilemma. They ate Folarin's mom's cooking and watched home videos for hours. It was an emotional gathering. Folarin's father, Festus, was a staunch supporter of his son and George Mason, but didn't fully understand how college basketball worked. Larranaga delicately explained to him the situation with the Wichita State game, the season at hand, how this was the program's best chance in its history to make history.

Festus Campbell slept on it. Prayed on it. Larranaga had empathy as a father and ambivalence as a coach. The next day, he received a call from Festus. Folarin would stay with the team while the rest of his family flew to Nigeria for the funeral. Folarin became upset.

"I really wanted to go," Campbell said. "At that time, when I was younger, whatever [my dad] told me, I did. But after that game, I kind of, I think everything happened for a reason. The way we won the game, the atmosphere, how the team played, it was so great. For us to win the game -- that was the only reason we got in -- if we lost that game, we wouldn't even be talking right now."

There was a second late obstacle and possible pitfall regarding a starter's availability for Wichita State. Three days before that game, Skinn and Drexel's Bashir Mason (now the coach at Wagner) nearly came to blows in George Mason's 67-48 romping of the Dragons. The officials took two separate trips to the monitor to review the incident, and it was only after the second review that both players were ejected. League rules stipulated that if you were thrown from a game for fighting, a mandatory one-game suspension immediately followed. Skinn was ruled out for Wichita State. Larranaga appealed to the national officiating board, and in that appeal it was determined the refs did not properly conclude after a first video review to eject the players. Within the rules, Skinn should have been eligible to play.

Wichita State's Koch Arena was the most intimidating environment George Mason played in that season -- until it faced Florida in the Final Four.

"It was something out of a horror movie," sixth man Gabe Norwood said. "I'd never been to Wichita. The school was kind of plopped down there. We got to the arena two hours before, and there's no one else in there other than the student section."

Campbell remembers the building shaking, his body compelled to sway because of how overpowering the din was.

"It was like all the fans were on top of you," he said. "So as they were yelling, I felt I was being moved from side to side because of how loud they were."

Assistant Scott Cherry: "That place is 10,000 people strong now. They've got seats filled an hour and a half before the game. Our guys go out for shootaround and their fans are killing them."

"It was the loudest game we played all year," Butler said. "And Tony had a field day."

Yes, George Mason won its appeal. And not only did Skinn play, but he was the deciding factor.

"It was a tremendous game," said current Maryland coach Mark Turgeon, who was Wichita State's coach at the time. "Big-time atmosphere. I remember George Mason not being intimidated at all and controlling most of that game. We made a run late. The thing I remember is how complete they were. They could drive it, shoot it, had defenders and their post players were so good. I remember saying after the game, 'That's an NCAA Tournament team.'"

With Koch Arena in a rave, Skinn took a pass from Jai Lewis on the right wing and put in the final three points of his game-high 23 on a winning shot with 10.8 seconds to go. Patriots 71, Shockers 68. As you'll discover below, that final play -- dubbed "3" -- was an omen to Mason's tournament success.

"The older and older I get, I see things do happen for a reason," Skinn said. "If I'm not playing in that game, maybe we're not having this conversation. Obviously that was a big game for us, and it was a program-changer."

It was national validation. The win put George Mason into the top 25 of the coaches poll for the first time. It was the victory that became the deciding factor in getting George Mason its controversial at-large bid. Without that win, GMU is an NIT team. Without that win, this story is not written.

BELIEVING THE UNBELIEVABLE

One twist: Mason's Final Four team was not as good as it should have been. That '06 run was all the more surprising considering the Patriots lost one of their most important players on the first day of school, when John Vaughan tore his ACL. Larranaga had him penciled in as a starter. Vaughan's medical redshirt was a blow to a team coming off a forgettable 16-13 campaign the year before. GMU didn't even qualify for the NIT in 2005; that season was a significant drop-off from the '03-04 team that won two NIT games and finished 23-10. It's overlooked now, but at the time that '03-04 group produced one of the best seasons in school history. GMU began playing basketball in 1966, and its 23 wins in '03-04 were the most in one season to date. The record-setting season was made possible in good portion by three players still finding themselves: Skinn, Jai Lewis and Lamar Butler.

In the summer of 2005 Larranaga told his staff the upcoming season could be the best in program history. He and assistant Scott Cherry scheduled ambitiously. They wanted to become the first CAA team in two decades to be good enough to qualify as an at-large. Like many mid-major coaches in the early 2000s, Larranaga learned how to manipulate the RPI. He wanted his players to play in terms of the unprecedented but achievable.

"We were thrown into the fire," Butler said. "You knew when you played against George Mason it wasn't going to be an easy night, no matter who we played. That summer we got good with swimming-pool conditioning, tire flips, a lot of new workouts. We knew we had the talent. The offseason workouts were actually workouts. Open gyms were competitive. It was unlike anything I'd seen in my years at Mason."

In the preseason he brought in an old friend from the University of Virginia, Bob Rotella, who is world-famous for his sports psychology work. (Larranaga credits Rotella's methods for pushing the 1984 Virginia team to a Final Four and for getting his 1997 Bowling Green team to its first conference championship in 14 years.)

So, on Oct. 30, 2005, Larranaga brings in Rotella, who asks everyone to put their heads down on their desks and dream about the year ahead. Butler reveals he believes the team can go to the Final Four. His teammates laugh.

But by the time they left that classroom in the physical education building on George Mason's campus, Larranaga was convinced every player on that team believed in what Butler had the audacity to say.

Everyone of course remembers those four huge games in March of 2006, but there were four other critical and defining games prior to the tournament that altered Mason's season and make this story even more inconceivable. After a five-point overtime road loss against a Wake Forest team that was ranked 18th that preseason, Mason lost by 20 at home to Creighton.

"The Creighton game was the motivation for our run," Larranaga said.

It remains one of the most embarrassing losses of his career. The next day, Larranaga held what he claims was the longest game film session he's ever had.

"We had to watch every single play, write something down about every play -- and it must have been 80 degrees in the locker room," Butler said. "We were scorching. It was a sweatbox."

The upshot of the blowout leads to two changes that alter Mason's season for the better. The first was taking Skinn -- who Larranaga had to concede was too shot-happy to truly play the point -- off the ball, and instead letting Campbell, a small forward, run the offense.

"My coaches thought I was absolutely crazy," Larranaga said.

The second decision came on defense. Larranaga and assistant coach/defensive coordinator James Johnson opted to play a pack line-type D. Larranaga swallowed his pride and abandoned his usual presses and traps. Instead, GMU would mind the gaps, clog the paint and force teams to shoot from deep. Mason evolved into one of the best defensive teams in the country, compounded by the fact it was not prone to foul. This was vital, as the Patriots lacked depth.

The second critical outcome came on Dec. 21 against Hampton, of all teams. If Larranaga's Creighton lecture was for the players, this lashing was for his assistants -- and it came following a 79-66 home win over a 1-6 Hampton squad. It was a wakeup call to a young staff perhaps not taking their jobs seriously enough.

"He was pretty heated," Scott Cherry, who's been the coach at High Point since 2009, said. "That meeting with coach got us mad but got us centered around the right things as assistants. Now being a head coach, I understand where he was coming from. We got a little fat and happy. We came back after Christmas, and from that point on our guys sensed a different thing from us."

Mason's season from then on:

- It lost once more in December

- It lost once in January

- It lost once in February

- It lost once in March

- It lost once in April

By the time the calendar turned to 2006, Mason was an anonymous 7-4 group, its four losses coming to the four best teams it played. What's forgotten: The 54-53 road loss at Old Dominion on Dec. 7 and the 63-61 loss at MSU on Dec. 30 both came on those teams' final shots. And Mason nearly won at Wake. It was a 7-4 team believing it should have been 10-1.

"A philosophy we had was to treat every team the same -- it doesn't matter if [it's] the worst team in Division I or the top team in Division I," Larranaga said.

Over the next nine weeks, Mason went 16-3, nabbed its precious signature victory with the road upset of Wichita State in the process and built an at-large case, should anything drastic happen.

Drastic arrived with a punch to the crotch. Literally.

SKINN'S PUNCH AND SELECTION SUNDAY

After Skinn skirted one fracas-related suspension in February, a second skirmish at the worst time forced Larranaga's hand. Hofstra was George Mason's foil that season. The teams played twice, the Pride beating the Patriots by an average of double digits each time. The second game came in the CAA semifinals. Skinn socked Loren Stokes in the groin with less than a minute remaining. Though most didn't see the jab, Skinn immediately admitted the act to the team in the huddle after it happened. A local TV cameraman happened to catch a low angle of the punch and showed it to Larranaga after the game ended. On his walk back to the locker room, the coach decided he was suspending Skinn, a senior, no matter what their next game was.

"In the heat of the moment, at 33 now as a coach, and at 22 as a player, your mentality is a lot different," Skinn, who's now an assistant at Louisiana Tech, said. "Frustration kicked in. I look back at it, and I was pissed off, and I knew once it happened there were going to be repercussions. Lesson learned and a lesson I needed."

Larranaga's decision drew praise from Mike Krzyzewski and Gary Williams, both of whom said they could not vow to do the same thing if they were in Jim's position. Skinn publicly apologized to Stokes and in the process cemented reinforced respect from his teammates.

"I did not want him to go out like that," Campbell, who spoke from Poland, where he's currently playing, said. "It looked bad in the media."

Skinn's suspension meant Mason's roster for its next game would not resemble Mason's roster that built a 23-7 record. The losses to Hofstra (which would fall in the CAA title game to UNC Wilmington) combined with this suspension led many to believe GMU spelled NIT. Mason was eliminated a week before Selection Sunday. It finished with an RPI of 26 -- very respectable and higher than any team in the CAA. (Hofstra was 30th.) GMU had a top-30 strength of schedule vs. Hofstra's No. 62. Hofstra's then-coach, Tom Pecora, openly campaigned for his team to be included above Mason.

A week of waiting that felt like a month of agony culminated with Larranaga inviting his team and about a dozen members of the media to his house in Oakton, Va., to watch the Selection Show. His wife, Liz, baked chocolate chip cookies.

"The longest couple hours of my life," Skinn said. "I didn't care about anything as long as they got a chance to play."

Before the Selection Show started, Larranaga turned the TV off.

"It was very, very, very, very tense," Johnson said. "Tony was tense."

Larranaga asked his players to envision themselves being selected. He told his guys this was the best team in George Mason's history and the best group he'd ever coached. He wanted them to flash back to that preseason meeting in the classroom when Lamar Butler put the Final Four on the table.

"Then I turned the TV back on, began to sweat, and wondered if I'd made a mistake," Larranaga said.

Then things got really strange.

"All of the sudden, someone called us and five minutes before it started, they told us (Joe) Lunardi put us in," Cherry said. "We thought that was kind of weird, and we're thinking, maybe he knows something. We don't know how. It was a ray of hope."

Other coaches and players also recalled discovering Lunardi's bracket projection changed to put Mason in just minutes before the CBS Selection Show began.

"I was telling Tony we were getting in and he was going to get to play in the NCAA Tournament," Butler said.

The Washington, D.C. region was the third to be unveiled. The top-right quadrant flashed MICHIGAN STATE and then it revealed GEORGE MASON.

"I remember Tony jumping so high I thought he was going to jump through Coach L's roof," James Johnson said.

The team, of course, went bonkers.

"I was there with my wife, and had my six-month-old boy, Brody," Cherry said. "When our name came up, I remember my son being woken up when we erupted. I remember looking at Tony, the look of relief on his face. He was going to take that with him, if we didn't get in."

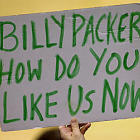

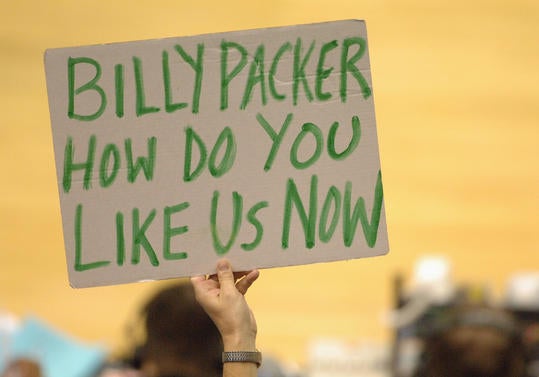

The team had a few minutes to bask in making history. It was the first at-large bid for GMU, which previously went dancing in '89, '99 and '01. The previous two trips came under Larranaga, but those teams were not the caliber of this group. It didn't take long for the Mason backlash to begin, though. Analyst Billy Packer led the charge.

"Packer and [Jim] Nantz ran through our non-conference schedule on the air, basically saying we shouldn't be in," assistant Chris Caputo said.

What made matters more interesting -- and controversial -- was who served on the Selection Committee that year. George Mason's athletic director, Tom O'Connor, was part of the process, as was Virginia athletic director Craig Littlepage, a longtime friend of Larranaga's, dating back to their time as assistants at UVa in the mid-1980s. Littlepage was chair of the committee that season.

"It was a fairly unremarkable selection weekend in that regard," Littlepage told CBS Sports. "George Mason was not subject to any more or less scrutiny than any at-large teams."

Littlepage said he wasn't certain whether or not Mason was the last team included, but according to his memory the Patriots were not the final at-large team above the cut.

"There were some that did not vote Mason to get in," Littlepage added.

Gabe Norwood remembers four stages of reaction.

"Joy, relief, celebration -- and then excitement when we saw the bracket," he said. "We saw that these were winnable games for us. It wasn't like we were in and that was good enough."

The committee could not have put George Mason in a better position. First up: Michigan State, which, the season prior -- months before it made the 2005 Final Four -- struggled to defeat none other than ... George Mason.

"Nantz and Packer helped us out," Cherry said. "Those guys came right out and said we didn't belong, we shouldn't have been there. It was a bad choice, that the committee made a huge mistake. ... Our guys already had fuel in their tank, and when they said that, it was all we needed."

THE MASON MEN

Every starter on that '06 team had ties to the area. The fact they were all regional recruits is what made the run extra special on a local level. Butler was team captain. A charmer and great ambassador for his school; they call him Mr. George Mason. The one whose face you probably remember, Butler was a stellar shooter and the guy most likely to be logging lonely sessions in the gym at odd hours. The type of player who's built to thrive on a big stage, evidenced by him eventually winning Most Outstanding Player of the Washington D.C. (i.e., East) Region. His heart was exposed on his sleeve and he was stronger because of it.

"What you saw on the court, that's what he's like in real life," Skinn said. "High-energy, super positive guy. Affable."

Skinn was 6-feet-small but sinewy. A feisty and fearless competitor who teammates said had the biggest heart on that squad. There was Allen Iverson to his game. Skinn landed at Mason after two stops at junior college. Larranaga offered him on the spot after watching him in an open gym in 2002.

Coincidentally, it was Bashir Mason of all people who was scheduled to visit to GMU right after Skinn. Larranaga told Skinn he only had room for one or the other, and he'd need a verbal commitment from him to ensure he'd get the scholarship. (He pulled the same move previously with Butler.) Skinn, who was finally starting to attract attention from other D-I schools, committed on the spot.

"I was just hooping man. I didn't know nothing about nothing," Skinn said. "No one had my back as far as the process. I hadn't even taken my SAT, and when I did I didn't qualify with the score I had. There was a chip on my shoulder and I finally got a chance with somebody that I thought did want me, and it was local, so it was a no-brainer."

Then there was Jai Lewis: Big, bright, smooth, nimble. The most naturally gifted and smartest basketball player on the team. Considered, endearingly, as a freak because of how much he could do with that wide, 6-foot-5 frame. He was fast, athletic, had great feet, great hands and splendid feel. Barkley-esque in that regard.

"We'd be doing sprints, you'd turn around and he's right behind you, this big man," Butler said. "He could do just about whatever he wanted to on the basketball floor."

Will Thomas was a quiet assassin, the son of a military man. His favorite words were "let's" and "go." His upbringing led to a neat-freak mindset hardened on the edges with a hatred of losing, a selfless attitude and a discipline never to talk out of turn. With Will, everything had to be done right. He cared about the details more than most. The coaching staff remembers getting one-word answers throughout his recruitment.

"One of the hardest-working players, toughest, most competitive kids I ever coached," James Johnson said. "When Will said something, everybody understood it was important."

Thomas wasn't a dynamic player -- the team would joke he only had one real move -- but that move, a left-handed hook, was automatic. It became an anchor to Mason's offense that season and was critical to the team's win over top-seeded UConn in the Elite Eight.

Folarin Campbell was George Mason's Magic Johnson. (Yet, for reasons still mysterious to some, his nickname was "Shaq.") An endearing loudmouth who loved the limelight and was a pleasure to be around, he didn't rattle and was long on confidence. He had a vibrant personality that lit up any room.

"He came in as a freshman and demanded respect, even if we didn't want to give it to him," Gabe Norwood said. "We wanted to make him earn it. He did -- quickly."

Many thought Campbell would attend Georgetown. That fizzled when, the day before he was supposed to take his official visit there in September of 2002, then-Hoyas coach Craig Esherick told him he'd taken another player. That player finished his Hoyas career with a 1.5 points-per-game average. Campbell, who is still playing professionally in Europe, became the floor general for the greatest season in George Mason history.

MICHIGAN STATE

Once his team was in, Larranaga became fixated on fun. He vowed he and his team would enjoy the experience more than any other in the bracket. It became a personal and public ambition. The team was unconventional in its approach. After it had what coaches described as an "awful" practice the day before leaving for Dayton, players held a makeshift game of Wiffle Ball at the Patriot Center to ease the stress.

Larranaga's will was tested again the night before the Michigan State game, when he was lying in bed with his wife. The hotel bar band's sound was bleeding through from one floor up. Liz insisted her husband call the front desk to get them to stop. Larranaga refused. He would not let anything bother him.

During GMU's public shootarounds, it did the unthinkable: It actually practiced its sets. MSU team managers picked up on this pretty quickly and scrambled to write everything down.

"Most teams are confident," Butler, who embodied fun more than anyone on that team, said. "We were very confident."

Larranaga didn't care who saw his stuff; he was thankful the turnaround wasn't for a Thursday game, that they got an extra day to prep for Friday. Coach L wanted his guys prepared but not rushed. After practice, he asked them to go into the stands, shake hands with fans and sign autographs. The idea being: There would only be one fan base in the building for certain cheering against George Mason. He wanted to do whatever he could to get every other fan rooting for the Patriots. It was a transparent and charming political move.

"Everything was light," Norwood said. "We took our job seriously, yes, but we enjoyed every moment."

Norwood was a junior that season, and his role suddenly became the primary story line for GMU-MSU. With Skinn suspended, he was starting in Tony's place. As you're seeing, things had a way of falling perfectly for George Mason that March.

"The year before, I had maybe the best game of my college career against Michigan State," Norwood said. "I wanted to win it for Tony. I wanted to give him a chance to play in the NCAA Tournament."

Teammates viewed Norwood as a sixth starter, and they were eager to see him flourish. He was a very good on-ball defender and was the most athletic asset Mason had. GMU was better in its defensive matchups for that one game because Norwood needed to be on the floor so much.

"He had toughness to him, his father being a football coach and his brother playing in the NFL," James Johnson said, referring to Jordan Norwood, who just won a Super Bowl with the Denver Broncos.

Skinn said his nerves were awful for that MSU game. He remembered how close Mason came to beating MSU before losing 66-60 the season prior. (Coincidentally, Skinn did not play in that game either, forced to sit because of a wrist injury.)

"I always had great respect for Jim," MSU coach Tom Izzo said. "It was one of those things, I think he's a damn coach good. I had a blue collar team, and so did he. Those forwards were tough. ... Shannon Brown and Mo Ager struggled to shoot it. Most importantly we got hurt down low. That was kind of surprising to me. But they were 6-7 and tough as nails."

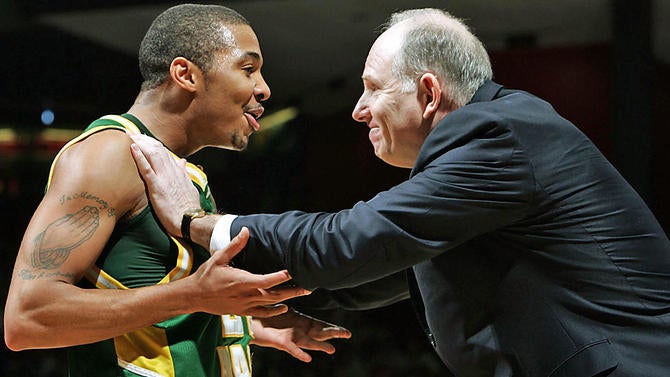

George Mason shot 59 percent and committed only 10 fouls in a clear-cut 75-65 upset over sixth-seeded Sparty. Lewis and Thomas combined for 31 points and 22 rebounds. Campbell had his best game of the tournament, going 8 for 8 and scoring a team-high 21.

"We came together and played for Tony," Lewis said. "We didn't want his last game to be known for hitting a guy in the nuts."

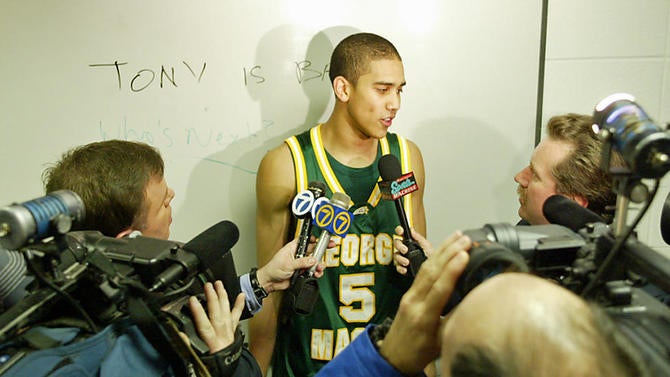

A forgotten fact: That was the first NCAA Tournament win in program history, and winning that day felt like reaching the Final Four -- little did they know. In the locker room afterward, every player but one mobbed Skinn. A few feet away, as the rest of his team was celebrating, Gabe Norwood was picking up a marker and writing a message on the whiteboard: TONY IS BACK.

"I got the chills just thinking about that," Norwood said.

James Johnson said "this is a guy who was the ultimate teammate" in retelling the memory of Norwood's gesture.

In the midst of an upset-themed opening two days of the tourney, Mason didn't stand out among all the other headlines just yet. Beating one 2005 Final Four squad wasn't good enough. It would now have to take down not just another '05 Final Four team, but the reigning national champions.

NORTH CAROLINA

The '06 run was when Larranaga's legendary, eccentric locker room speeches became known outside of the Mason program. His pep talk prior to Carolina was vintage Coach L. He referred to how UNC fans saw their program's players as gods -- Supermen. Then he told his guys to look at their green uniforms. Green. As in kryptonite.

Then someone brought out a mini boombox and Larranaga, 56 at the time, pushed play. He began to dance. The team absolutely lost it. The song was "Kryptonite" by Big Boi and the Purple Ribbon Allstars.

"Seeing Coach L doing that before a serious game, it got us all in a relaxed state of mind," Campbell said.

Too relaxed at the start. Carolina smacked Mason with a 16-2 opening run.

"That was a scare," Jai Lewis said. "I believed in the first four minutes of the game our season was over."

Sure. Mid-major team shocks college hoops big boy in the first round, then gets dispatched two days later in the Round of 32. That's how March usually works for most small schools who get to enjoy 48 fleeting hours of bliss on a national stage. But, in this spot, it's important to emphasize just how perfect a pod that first weekend was for the Patriots. Just as Michigan State was an ideal first-round foe, UNC -- yes, North Carolina -- was a beatable blue blood.

In the first timeout, Larranaga refused to let his players sit. He told his team to remain standing and to look at UNC's bench. They were celebrating.

"I said, 'We got these guys right where we want them,'" Larranaga said. "'They think this game is over, and we haven't even begun to play.'"

Norwood started the game, but Skinn -- suspension now over -- checked in.

"You're thinking in the back of your head it's almost time to go home," Skinn said. "Those 16 points felt like 35."

Skinn's desperation 3-pointer from 24 feet with the shot clock set to expire banked in, making it 16-5. A few people interviewed for this story said it was the most important shot of the game.

With UNC threatening to blow GMU out, Larranaga was about to coach one of the best games of his life. He refused to show his hand; he wanted UNC to go into halftime without any notion of needing significant adjustments. Mason's advantage was assistant Scott Cherry. He played at Carolina and was on the '93 national title team. After dropping an overseas career in the '90s, he sold forklifts in Greenville, N.C., only to find his way back to basketball after three years. Cherry thoroughly predicted what Williams would run because Williams learned from Cherry's coach, Dean Smith.

"We didn't feel like they were going to be a team that was going to overpower us like typical Carolina teams," Cherry said. "It wasn't hard to prepare for them. UNC plays fast, there's a lot of possessions, so you've got a lot of chances."

Larranaga bailed on his man-to-man scheme, instead inserting a 3-2 matchup zone for the first time all season, and behind that, a tide was stemmed and the Patriots trailed 27-20 at the break. It was an old pull for Larranaga who, as a young assistant, helped coach Virginia to the 1984 Final Four because of that exact defense. Will Thomas, always assigned to defend the best big man, held national Freshman of the Year Tyler Hansbrough to 10 points and three turnovers.

"We never took any opponent for granted, no matter who, and that's why we were good in the tournament and why big schools fail," Skinn said. "When that competitiveness isn't reciprocated, then you have a ballgame."

Mason came out of the second half and completely shook Carolina by dosing the Heels with their own medicine. Larranaga unleashed the Dobermans, calling on his dormant press out of nowhere. The Patriots hadn't used it all season. They forced four straight turnovers and took the lead. Williams called timeout. Larranaga again asked his team to look at the Carolina bench. They weren't celebrating this time; they were arguing. Later that half Williams got so angry he slammed his chair to the floor.

GMU's discipline not to foul was never more critical that season than in this game. UNC took four free throws the entire contest; Mason had eight fouls total. GMU won 65-60 and became the third CAA team in history to reach the Sweet 16.

"I was very surprised we won," Campbell admitted.

In an interview for this story, Norwood shared publicly for the first time what that game meant to him. Larranaga rewarded Norwood with a second straight start because of how well he played against Michigan State. What no one knew then was how Norwood grew up idolizing UNC. He wore No. 5 because of former Carolina point guard Ed Cota. When he was 10 he wrote a letter to Dean Smith, asking to be recruited. Smith wrote back; Norwood still has the letter.

Mason's Sweet 16 run leads to Lamar Butler landing the cover of Sports Illustrated. The plane ride back was pandemonium. Ragtag boosters, band members, cheerleaders. When they got back to campus on Sunday night, an arena full of fans was waiting for them. This after George Mason failed to sell out even one game that season.

WICHITA STATE 2.0

It took a beat for most to realize, but Mason's players and coaches saw it immediately on Selection Sunday: We reach the Sweet 16, we play the second weekend in our backyard. The Patriots won their way into the Washington, D.C. regional. And now they were a local phenomenon in addition to a national sensation.

"For the first time in the history of the area, it became a George Mason town," Chris Caputo said. "After the Redskins, it's a basketball city. The Big East and ACC are intertwined there. It had never been anything but a Georgetown/Maryland town. I remember seeing people on the streets wearing George Mason gear, and it was really surreal for that to be happening."

Mason players congenially embraced two days worth of hometown attention from fans, students and media. Jai Lewis said a five-minute walk to class became a half-hour meet-and-greet. Lamar Butler recalled ordering a cheeseburger on campus, then getting up to go to practice 45 minutes later having never taken a bite.

"That burger was ice cold because I got caught up talking to fans and media," he said. "The cheese wasn't even melted anymore -- it was back to being cheese."

There was also an element of stress in the lead-up to the Sweet 16. Since almost every player on the roster grew up less than 30 miles from D.C., tickets for friends and family became an issue. Players had to turn off their Nextel flip phones to preserve their batteries and sanity. Calls and texts flooded in from people they had not heard from since high school. Skinn put an outgoing voicemail message on his phone alerting everyone he did not have tickets for them.The team got solace and silence by staying just over the Potomac River, in Crystal City.

"I think it was smart for us," Butler said. "College kids being on campus at that time might not have been a good thing. Thank god we had a mature team and didn't let that stuff go to our head. It was definitely hard to focus because, nationally, we were the one team that was allowing full access to the media. We were approachable for everybody."

At the shootaround the day before the regional semifinal, more than 10,000 fans showed up to watch practice. The state of the city and team in that moment is lost to the Final Four run now, but players recalled how incredible being a Sweet 16 team was.

It's rare for non-conference teams to meet in the NCAAs after facing in the regular season. And it's like a comet to see it with mid-majors. Wichita State was a 7 seed that upset No. 2 Tennessee -- a group Larranaga believes would have likely beaten George Mason. Instead, the Patriots had the pleasure of getting a Shockers crew they'd already defeated in Wichita a month prior.

"That game was over before it even started," Cherry said. "We didn't have to tell them anything. Wichita State walked into that building and you could see the looks on their faces. They knew they were in trouble."

To a man, every GMU player interviewed for this story echoed Cherry's words. They remembered how Wichita State looked fraught the day before, at media day.

"We knew there was no way we were going to lose this game," Campbell said.

Turgeon tried to emulate what Hofstra did in its two wins over Mason that year, but it was to no effect. GMU won 63-55, but it was never a close game.

"I don't know if we were intimidated by who were playing." Turgeon said. "We might've been intimidated by who we were playing and the environment. It was electric in there. It was an amazing crowd. We could have played them 100 times and probably wouldn't have won 99 of them in that building."

Mason's win came on Friday night before No. 1 UConn escaped in overtime against a talented Washington team. Just as Larranaga thought Tennessee would have likely beaten George Mason, he also believes Washington would have been tougher than UConn. Strange, right? But Larranaga didn't want UW because 1) He thought his guys would have no shot at stopping Brandon Roy, 2) It was the only opponent his players had no familiarity with, and 3) UConn being the No. 1 seed offered the final carrot of motivation.

"If we had beat Washington it would not have been as big as beating Connecticut," Larranaga said. "I wanted UConn to prove how good we were. ... This is exactly what you want as an underdog, because no one gives you a chance except you. Could we beat them three out of 10? Maybe not. You only have to beat them one time."

"BY GEORGE, THE DREAM IS ALIVE!"

The Elite Eight in one sentence: Connecticut lost because it disrespected George Mason and that really pissed the Patriots off.

"I remember Denham Brown before, when he was at the press conference," said Jai Lewis. "He was coming out saying they were going to beat us and it was going to be an easy game."

When asked, most Huskies couldn't name a GMU player. They thought GMU was in the Patriot League because its nickname was the Patriots.

"For them to say they didn't know who we were or where we were from, it was a slap in the face," Norwood, who spoke from the Phillipines, said.

Mason players watched ESPN from their hotel room and were texting each other, riling themselves up.

"Man, we play you tomorrow," Butler said. "Either you don't care or you don't respect us. That was all we needed to get ready. If you don't know us now, you'll know us by the end that game."

The only UConn player who knew anyone on Mason's roster was Rudy Gay, and with good reason. Will Thomas, still, has never lost to Gay. His Baltimore high school team beat Gay's seven times in four years, twice in the Catholic League championship. Those wins didn't land Thomas interest from high-major schools, and it bothered him.

"You only see teams like UConn, Duke and Maryland on TV, so that's the colleges you want to go to," Thomas, who spoke to CBS Sports from Spain, said. "You don't see George Mason on TV. When they started recruiting me, I had no idea where or who George Mason was."

Thomas got to 8-0 against Gay on March 26, 2006. The ice broke for Mason when, on its ride to the arena for the game, the team bus crashed into a parked car.

"We had a police escort, we were flying," Larranaga said. "I thought, We're going to be late for the game. The police escort said, 'Don't worry about it, he was illegally parked. You keep going. I'll have him towed.' Our players roared laughing and we just kept rolling from there."

Remember, Jim Calhoun's team wasn't just the No. 1 seed in its region -- the Huskies were regarded as the best team in the country. UConn had the best frontcourt in America and led the nation in blocks. Six players from that team play(ed) in the NBA, with four of them taken in the first round. It would have been seven future pros for that UConn crew had top-10 pick Andrew Bynum not de-committed from the Huskies and put his name in the NBA Draft out of high school. (Tiny twists make the Mason run that much more folkloric. If Bynum is in a Connecticut uni, does this story ever get told?)

Before the game, Larranaga again played "Kryptonite." But his final words initially confused the team. He reminded them how UConn didn't even know what league Mason was in.

"You guys are in the CAA."

Players were like, "Yeah, coach, we know."

"No, the CAA," Larranaga said. "The Connecticut Assassin Association!"

The locker room detonated. But just as the incredible UNC pre-game speech didn't lead yield immediate dividends, Mason fell behind early to UConn, 16-8.

"I just remember thinking, we're going to have to keep scoring because I don't know if we can stop them," Cherry said.

The Verizon Center had a respectable UConn contingent, but it was undeniably a Mason crowd. Calhoun said it was "a national championship crowd." Cherry remembered talking to people who'd been to many kinds of games there. They said the place never reached as fevered a pitch as it did on that day.

"Even though we had belief in ourselves, in modern college basketball there was nothing you could point to that you could make the Final Four as a mid-major," Caputo said. "Back then, people would wonder if one could ever do it."

It's an incredible game to go back and watch, objectively one of the best in tournament history. It's not just the David-Goliath element and the unprecedented ending. The game was so well played. Mason could not win defense-first, the way it did in its previous three games. It had to take off the chains and go.

"In [2006], we had one point guard on the team," Calhoun said. "It was our flaw. It was a very talented team up front, but the best teams I've had were when we could beat you at two positions. If (Marcus) Williams didn't have a great game, we didn't have a great game. We did not have a great tournament yet made a final eight because of what we were: powerful. When a team like us -- the No. 1 seed -- when we're up six, we're in trouble. When they're down six, they got us just where they want us."

Campbell was put on Gay, UConn's best prospect. It was the toughest assignment of his career to that point.

"That whole team was big," Campbell said. "That's what makes it better, a more memorable game for us."

The teams combined for 20 turnovers and shot 49 percent. No one fouled out. There were a handful of awesome shots, including Campbell's acrobatic and-1 layup to end the first half that cut UConn's effortless run and lead to 43-34.

"Had the ref called a charge and wiped out the basket, we probably never would have won the game," Larranaga said.

In the second half Mason finally took the lead on a 3-pointer from Butler with 11:09 to go, capping a 14-4 run. From then on all pressure was on UConn. Crazy fact: Mason played its starters for the the final 15:37. And for most of that span, that same, simple play that Larranaga called in Wichita that led to Skinn's winning shot in February -- "3" -- became the team's only offense. GMU's staff was shocked UConn opted not to double-team, but Calhoun clarified he did call for it once in the second half -- and on that play Mason nailed a 3, so he never doubled again.

"They outplayed us up front, which is still shocking to me," Calhoun said. "But I've been in those situations. They believed in themselves and they caught us and were able to expose by beating us at what we could do, not what we couldn't do. They did things to us that teams hadn't done to us all year. Basketball is all about accenting what you are and hiding what you're not."

UConn refused to double in the post, and some chemistry issues were exposed. See, Larranaga did not allow his players to wear headphones when they had team activities or while walking around campus. He wanted open communication and for his players to be accessible.

"And I remember this," said Norwood, "because as we were walking in together at media day, UConn was walking out, and it was one of those things like, none of them were talking to one and other. It was almost like they didn't like each other, at least compared to our team. We're cracking jokes, laughing. I don't know if they were trying intimidate us or what. I don't know what it was, but it was two totally different dynamics. As we went into the game, I wondered if we could get them on the ropes, if they would really be able to lean on each other."

The fracture materialized when Gay kept UConn going late in the second half. After he hit a mid-range shot to give UConn a 63-62 lead with 6:11 remaining, Butler remembers Gay yelling at Marcus Williams.

"He said, 'Pass me the f---ing ball,'" Butler said. "And after that Williams shied away from doing just that."

Mason should have won in regulation. One of the dozen or so "OHMYGOD" moments came when Williams cut GMU's lead to two with 7.9 seconds to go. Butler said he couldn't hear Larranaga over the arena noise in the ensuing timeout. On the next play, Skinn, an 81-percent foul shooter, missed the front end of a one-and-one. Williams fed a streaking Denham Brown, who went under the rim and released the ball with 0.2 seconds on the clock. It bounced three times on the rim. Bucket. Overtime. World on fire.

"You're not supposed to be winning, and every [UConn] shot looks good," Skinn said. "I remember thinking, You idiot. You missed those free throws. Now we're going into overtime and we're definitely going to lose."

The '92 Duke-Kentucky epic is probably the only regional final better than UConn-Mason. Think of the backdrop: Calhoun recalled how his team got a real scare from No. 16 Albany, then barely beat eighth-seeded Kentucky by four. Brandon Roy and No. 4 Washington took UConn to OT and probably should have won in the Sweet 16. Calhoun admitted he never had a comfort level with his team that season. They were great in spite of their pieces. And here they were again, seemingly nudging off tournament death.

As UConn regrouped before overtime, Larranaga stood a few feet from his team. What came next is a moment every single GMU player and coach interviewed for this story remembered exactly the same way. Larranaga swears these were his exact words: "Guys, we didn't play defense for five seconds, and now we've gotta play great defense for five minutes. But you know what? There isn't any place on earth I'd rather be than here with you guys, playing Connecticut with a chance to go to the Final Four. Where else would you rather be? Are you having any fun yet?"

The only shot that stands the test of time from that OT is the one that did not go in: Denham Brown's missed 3-pointer to end of the game. But there were two shots from Mason everyone connected to that team remembers. No. 1 was Thomas scoring the first points of overtime. It gave the Patriots a similar feeling of calm the way Skinn's banked-in prayer against UNC eased the tension in that game. The second shot was courtesy of Campbell, who hit a gorgeous fall-away from the right side over the lankly Gay to put Mason up 84-80 with 1:13 left. Campbell still deems it the biggest shot of his life.

But of course, it's the miss that we remember. If Gordon Hayward's half-court heaveagainst Duke in the 2010 title game is the most famous miss in NCAA Tournament history, Brown's miss qualifies as the most shocking. Because UConn is not supposed to lose that game, not to George Mason, not with the Final Four in the balance. The play unfolded almost identically to how the Huskies got the game to OT.

"Denham Brown dribbled right by me, and I was so tempted to knock the ball away from him," Larranaga now admits. "I was thinking, God, I wish I could just hit that thing."

GMU again missed a foul shot (Jai Lewis this time) with 6.1 left. Brown gets the rebound and hurries up the court.

"The ball was in the air for the longest time ... it took forever," Campbell said. "As the shot went up, I was praying he didn't make it."

Brown gives Campbell a little push, then steps back to launch. Campbell said he "jumped out of his shoes" trying to contest the shot. On the bench, Gabe Norwood drops his head in fear, convinced -- like pretty much everyone else who understands how the universe works -- the shot is going in.

Only it doesn't. The universe hiccups as the ball harmlessly nicks off the rim.

"When I heard the buzzer sound, I was looking down at the floor," Norwood said. "I only saw feet. Tim Burns was on one side of me, John Vaughan was on the other. When they jumped, I jumped."

Time is done, the game is over, but still Lamar Butler hustles for the rebound.

"At that point in the season, once you doubt, you're out," he said. "Even when the shot went up. I made sure they were not getting this rebound to win this game."

Butler and Skinn run to the George Mason section. Coaches and players sprint diagonally across the court to join them. Skinn's jersey is already off, and it's instantly a TV highlight that will last for a hundred years if not longer.

"We won that game off the court," Butler said. "Down the stretch, as times got tough, they started fighting. They weren't a team. We were huddled up, every time."

Butler was joined within minutes by his dad at midcourt. Lamar grew up 15 minutes from the arena where he just made history. As father and son hugged, Larranaga looked on from a few feet away, his eyes welling. Butler credits his father for teaching him the game, and Larranga for showing him to have fun playing it.

"Those moments are memories that last a lifetime -- that took a lifetime to get there," Larranaga said.

Players recalled seeing faces of fans who supported the program dating back to its D-II years. These were local diehards who lucked into having the hometown team play right there in their city -- and pull off the most unpredictable Final Four run in college basketball history.

Campbell vividly remembers taking the bus back to campus, getting there very late -- and seeing the parking lot filled with hundreds of cars.

"Man, like we had another game there that night," he said.

Said Calhoun: "George Mason became, to me, they became a symbol of what is great about college basketball."

THE DANCE FINALLY ENDS BUT THE LEGACY NEVER WILL

With its red-letter run through the region, the Patriots beat a Michigan State team coached by a man who's made more Final Fours than anyone this century; twice defeated a terrific mid-major program; and downed both the 2005 national champions (UNC) and the 2004 national champions (UConn). If Mason's season had to end in a loss, it was fitting it fell against Florida, which went on to win the next two national titles. A forgotten fact of that '06 Final Four: That was the first time in the modern era wherein none of the 1 seeds made the final weekend.

"I think we helped set the precedent of mid-majors being able to be in the [Final Four] discussion," Skinn said. "You saw it years after. A lot of guys play college basketball at all sorts of levels, and you have a small amount that say they have played in the Final Four. From a university standpoint, it's a blessing [that because of] basketball everyone across the world knows George Mason."

The school's admission application numbers spiked in the months following the Final Four. The campus bookstore sold more than $800,000 worth of merchandise that March alone. A university study conservatively estimated GMU's Final Four run to be worth north of $677 million in free advertising. On March 27, 2006, GMU appeared on the front page of more than 100 newspapers across the country. Buildings were added on and around campus. Out-of-state enrollment has grown by 32 percent in the decade since.

"We were the Roger Bannister of college basketball," Caputo said. "VCU, Wichita State and Butler came after. Those programs had been getting money pumped into them for years. There can never be another George Mason."

The team's run is ever-praised now, but the players did not handle the Florida loss well. That was in part because -- to a man -- they all believed they would have been playing in the national championship had they drawn LSU or UCLA instead.

"There was no sense of, 'Hey, guys, don't worry about it, we're a small school, we weren't supposed to be here anyway,'" James Johnson said. "There was none of that. Guys were emotional. We should have won. I don't think at that time they had a chance to even look and think about what they had done."

Will Thomas knows he didn't.

"I never stopped in the moment to think about it," he said. "Years later I've thought, 'Wow, I actually went to the Final Four.' But during and while it was happening, no. It was just too much."

Butler could not watch a replay of the Florida loss -- until last March, during the tournament.

"It was time for me to face the demon that had been haunting me for nine years," he said.

He watched it once, called Larranaga as means of therapy, then put the DVD away. He has no plans to watch it again any time soon.

Campbell and Thomas went on to become top-10 scorers in program history. Thomas has the third-most rebounds at GMU and Campbell ranks fourth in career assists. Norwood, who is still playing, wound up landing the most successful, stable overseas career. Skinn, Lewis and Butler have since retired from basketball and remain best friends.

"Coach L changed my life," Lewis said. "I saw him two weeks ago and told him that."

Campbell never made it to Nigeria after his grandmother passed and, tragically, Festus Campbell died at 55 in 2012. The plan was always for them to go together. Without his father alive, Folarin has no urge to visit his family's home country. Larranaga, as coaches often do with their players, has remained a mentor to him.

"The best coach I've ever had," Campbell said. "He gave me confidence that, to this day, I wouldn't have and wouldn't be the player I am now. I love him. He's done a lot for me and my family. I remember him saying at George Mason he wanted to be an ACC coach. I'm glad he's gotten that opportunity and he's doing so well."

Larranaga's 271 wins at Mason are more than double the coach in second place. And now he is having a late-career revival. His Miami Hurricanes team this season has a great chance to do what GMU accomplished 10 years ago. In his office, Larranaga keeps Mason mojo in the room. He has a big, signed Final Four poster and the five bobbleheads of those starters. He has a Final Four chair and a plaque with his picture on it that says "2006 Washingtonian of the Year." On his desk is a George Mason snow globe and a rock that shares the same color for Miami now as it did then for Mason: green.

Kryptonite.