Chicago. Home. Where the family is. Perfect place for an unforgettable night in a tiny, half-filled gym, Illinois-Chicago's UIC Pavilion. It's Feb. 26, 2015, the night Green Bay's Keifer Sykes plays his final game in his hometown area, in front of a band of family and friends. Sykes had nearly 100 ticket requests for this game, and he will not disappoint the familiars.

The two-time Horizon League Player of the Year scores a career-best 36 against UIC, helping the Phoenix win 72-67. Sykes cashes a deep 3-pointer as time expires at the end of the first half. The basket pushes him past the 2,000-point total for his career, keeping him on pace to be one of the five most prolific scorers in Horizon League history and making him the first player ever in that conference score at least 2,000 points, grab 400 rebounds and dish 400 assists.

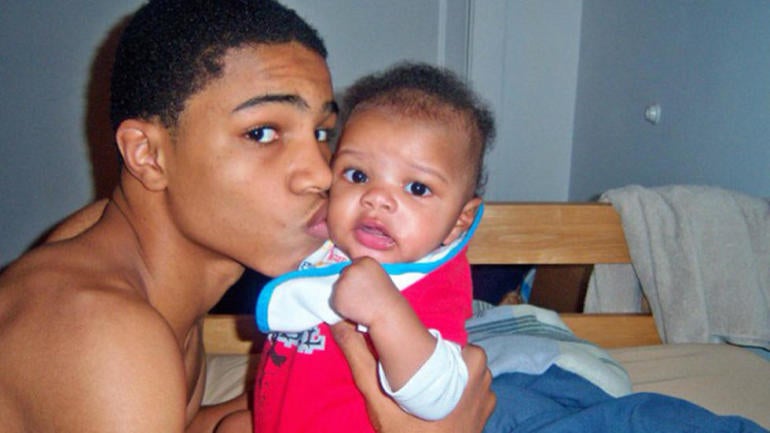

Afterward, he takes dozens of pictures and shakes the hands of nearly 200 people, plenty of whom he does not know. This is a blessed, beautiful evening, and it's blessed and beautiful because it ends the way Sykes wants every game to end: with a boisterous embrace of his son, Keifer Sykes Jr. KJ, they call him. The 4 year old sat behind Green Bay's bench, in section 115, watching his dad make history last Thursday. Sykes' son represents an overlooked and under-discussed fact of life for so many college athletes: fatherhood. Inconvenient, opportunistic, stressful, hopeful, problematic, irritating, invigorating, a blessing all at once.

"He's a ball of fire," Green Bay coach Brian Wardle said of KJ. "You can hear him in the stands. I've heard a couple of times him screaming, 'Go, Daddy!' when he's on the foul line. We treat him as one of us. The big thing with me is, I want Keifer to be a good father first. Every year he's gotten better at balancing and understanding that. I want the kid around. If he's in town, have him around practice, around the locker room. He's a good kid; he's not a distraction."

Sykes, 21, just won his second straight Horizon League Player of the Year honor. He's second on Green Bay's all-time scoring list, a mutantly athletic 6-foot-tall NBA prospect trying to will the program to its first NCAA Tournament bid since 1996. To him, these are secondary anecdotes. He's got a goofy personality and caring heart but also boasts a paternal side that's as sanguine as it is dedicated. First and always, Sykes prides himself on being an awesome dad. He and KJ communicate every day; KJ can unlock an iPhone and FaceTime in no time. It's scary how fast he is at it.

"It's not easy," Sykes said of juggling fatherhood with basketball and an impending graduation. "It's fun, though. That's the thing. People think it's hard, and it is, but when I'm around KJ, that's the only time I can really get away from [basketball]. After a game, win or lose, I walk up to him and he's just laughing. Being silly. I'm still frustrated we lost, but now I'm like, that's over with. There's more to life than basketball. When he's running around, jumping, having fun, I can't do nothing but laugh. He's the boss."

Sykes, who these days has NBA scouts frequently traveling to gelid Green Bay, has previously bypassed chances to turn pro early in Europe. He'll do it if it becomes absolutely mandatory, but for now, he refuses to leave KJ. Going to Europe would mean Sykes, who is not married and not dating the mother of his child, could not bring KJ with him.

"I do not want to go pro overseas," he said. "I don't want to go out of the States. When I first committed, I didn't know where basketball would take me. I knew my mom couldn't afford college. I went to basketball for free college. Free schooling."

Almost nothing about Sykes' life or current situation is normal (he impregnated his then-girlfriend, Allyne, when he was 15). But in talking to dozens of college coaches for this story, you discover that that this is a more common situation than you might think. All coaches who were asked estimated that more than half the teams in Division I men's basketball currently have at least one player who is father, or a father-to-be, on their roster. Most guessed higher than 75 percent.

***

No one taught Branden Dawson how to be a father. His dad is alive, but he's not around and never has been. How long has it been since Dawson spoke to his dad directly? Without an iota of resentment in his voice, the Michigan State star answers: three years. Branden does not carry his father's last name.

Though each situation is different, if there was one player whose circumstances most resembled Sykes', it's Dawson's. Like Sykes, he's a senior NBA prospect. Like Sykes, he opted not to turn pro early despite having a child to feed. Like Sykes, Dawson's been a father since he was a junior in high school. His son, My'Shawn, was born March 30, 2010. And like Sykes, when Dawson found out he was going to be a father, he had zero interest in letting his mother know right away what he'd gotten himself into. A chain response of fear, as it often does with teen pregnancies, triggered a stress reaction.

"She was really scared to tell me," Dawson said of his girlfriend's pregnancy. "When she told me, I kind of freaked out. I just wanted to run away [from it]. I was afraid to tell my mom."

Dawson grew up with a mother who loved him dearly and worked at a local hospital -- the same one My'Shawn was born at -- but there was a wall of fear he couldn't mount. After waiting for months, Dawson found the courage while plopped on a bus headed to Milwaukee. He was on a trip for a basketball tournament, and that's when he called his mother at work.

"This is not the time for that," Cassandra Dawson told her son, thinking he was kidding. He wasn't. Branden had lost "significant weight" and was unable to consistently eat due to anxiety. He also became nervous regarding his recruitment. Having not yet committed to Michigan State, the stress of choosing a college only added to Dawson's ongoing personal strain.

Think back to high school. Imagine sitting in a class, your leg jackhammering the tile, waiting for a phone call to come. The biggest phone call. Dawson remembers that. He remembers hopping into a car after getting that call, riding with the aunt of My'Shawn's mother, a 10-minute drive to Methodist Hospital. They were Dawson's final moments without having the responsibility of another person's life in his hands. He was 16.

"When I got there, I was nervous, and it was kind of surreal," he said. "I was pacing in the waiting room. I forgot to even call my mom. I was freaking out. Everything was going so fast."

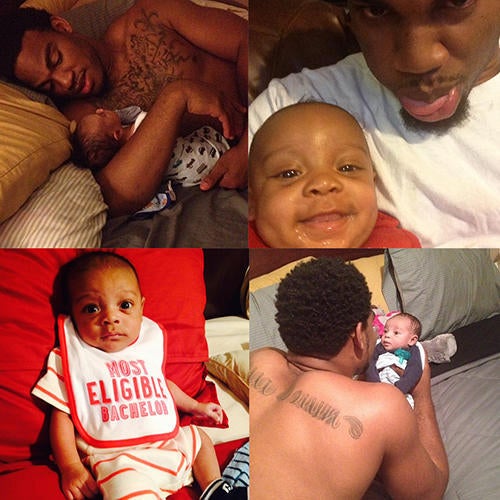

Dawson's first two years at Michigan State consisted of few visits with My'Shawn during the season. After a game at Indiana in 2012, Dawson asked coach Tom Izzo if he could ride with his family from Bloomington to Indianapolis to escape and spend one night with his son. Now, after seldomly getting to see his him early in his college years, Dawson's senior season has been a change for the happier.

In this, Dawson's final year at Michigan State, My'Shawn has lived with him, the two of them bonding, sharing meals in a small off-campus apartment. My'Shawn's mother lives back in Indiana; it was her idea to have father and child live together this season, in part because she's working night shifts at a Speedway to save money and find some quiet that was lost during the early years of My'Shawn's life.

My'Shawn's been to almost every Spartans home game this season, sitting with Dawson's high school coach, Johnny Ryan, and a former teammate, Devonte Harris. These are the guys helping Dawson, watching the little one when he's away, driving My'Shawn to and from pre-K school sessions. For more than a few college athletes, this is the side of life the public does not see. It's a dimension some critics didn't realize when they were all too eager to bemoan Dawson's performance in MSU's loss last Sunday at Wisconsin, wherein Dawson had four points and two rebounds. Afterward, Dawson revealed his son was taken to the hospital two days earlier on account of pneumonia.

According to dad, My'Shawn's "not the typical kid who wants to come home and watch cartoons." He'll want to turn to ESPN and watch a basketball game. And when Michigan State's got a road game, he'll ask Johnny or Devonte, "Is that my dad playing?"

"Is the game on yet?"

"Is that my dad?"

***

Keifer Jerail Sykes, born Dec. 30, 1993, is the last child in his family. He has just one full sibling, James Sykes Jr., and seven more half-siblings: DaVon, Jarvis, Kristie, Jameeka, Rashaunda, Shakeeya and Antwan. Nine children from five mothers and two fathers.

Sykes keeps in touch with all of them but he hasn't seen Kristie and Antawn in years. They last shared space together in 2012 -- at Keifer's father's funeral. The unexpected death came a month removed from the end of Keifer's freshman year. Every situation is different. Whereas Dawson did not have a prominent father, Sykes' relationship with his was irrepressible.

"Loved James Sykes. A tremendous man," Wardle said. "As a coach, you would love to have all parents talk to him in a lot of ways. He was just a really good man."

James Sykes died of heart failure on June 6, 2012. Wardle answered his phone that afternoon to hear the mother of his talented newcomer crying on the other line. Lisa Sykes was asking her son's coach to tell Keifer his father was gone because she couldn't bear to do it. Wardle describes it as the hardest situation of his career, far beyond anything he faced during the summer of 2013, when accusations of verbal mistreatment from former Green Bay players threatened his job. (Without prompt, Sykes publicly defended his coach throughout the ordeal.)

When Wardle got to Sykes' dorm room, the 18-year-old was sitting alone on his bathroom floor, sobbing. One of his brothers had called him before Wardle could break the news. His father, his best friend, was dead.

"I don't ever want to go through that as a head coach again," Wardle said.

Keifer prides his relationship with his son as an extension of what he had with his dad. He was closer to him than any of his other siblings. James Sykes, a former vice president of the Broadway Armory Park association, is buried at Memorial Gardens in Homewood, Illinois. Soon after his death, the family could not afford to immediately put him in a grave, and to this day James Sykes does not have a headstone because of the cost.

Keifer says his first pro basketball check will go toward buying and engraving a tombstone for his father.

***

It's a seven-hour drive round trip from Green Bay to Chicago. Sykes estimated he's trekked it back and forth about 20 times per season over the past four years. Sometimes he'll drive to Chicago, pick KJ up, stay for but a few minutes, and head right back to campus.

Sykes grew up on southeast side of Chicago, on East 67th Street and South Cregier, in a project apartment complex. A family of seven crammed into a two-bedroom place, where they lived until Sykes got to high school. When the family moved into a three-bedroom place on the west side, "We'd have a bedroom, three boys on one side, three girls on one side," Keifer said, "and sometimes the boys would share the couch."

In high school, Sykes would ride alone on the green line to Marshall Metro High -- the team featured in the beloved basketball documentary Hoop Dreams -- where he played his way onto varsity and would become a McDonald's All-American honorable mention. Sykes didn't like the recruiting process -- at all. Keifer's always been a person purely at comfort around family and only his family. He is at Green Bay because that staff impressed his father. At James Sykes' urging, and Keifer's own interest in ending the courtship of so many other coaching staffs, he committed fairly early as a junior.

"I didn't expect much out of basketball," Sykes said. "I wasn't trying to map out a strategy to go pro. There's too many [coaches] calling me. I didn't have goals to go further. It's free school, and I'm getting it, so let's go."

Why is Keifer the father he is? Sykes, a self-described daddy's boy, wasn't worried that being a father might hurt his chances in recruitment. Really, he worried about leaving his son, how KJ would be without him, and not so much about what the schools thought of his situation or the backstory on his complicated family structure with a troupe of half-siblings.

It's about mom just as much as dad. Lisa runs an out-of-home daycare operation. She's long had a keen love for caring for the young, something as immediately evident in Keifer as his flaring athleticism.

After Keifer impregnated his former girlfriend, Allyne, he was horrified to tell mom. He kept it from her as long as possible; the "entire school" knew about it, but she didn't. Until she did. Every mom always finds out. (In this case, an ex-girlfriend of Kiefer's told her.) One afternoon Keifer was on the green line, headed back home, when he got a call. There was yelling on one end of the line and a 15-year-old stomach swirling to mush on the other.

"At this point, she's three months pregnant," Keifer said. "I walk in the door, my parents are sitting at the table. Waiting. My mom's going crazy, and my dad was taking heat. 'I told you don't let him go to that school.'"

But the most important thing said that night: "The child will be taken care of." From mother to son.

"The milk is spilt all over the place," she recalled saying. "I had my first child when I was 20. I didn't want my children to go through that. I told them, 'Don't have any babies. Life is too short. Go to college, live your life. Don't do what I did.'"

Keifer's parents met when fate played a chord. Having seen each other from afar in previous years, they met again, of all places, in an ER when she was 23. Lisa was there with her cancer-stricken mother; James was there tending to his niece after she'd been assaulted in a domestic dispute. The two began dating and created a family out of wedlock. Keifer, whose birth was not planned, came two days before 1994.

Five and a half years later, James and Lisa Sykes married, on April 27, 1999. Keifer, along with six of his siblings and half-siblings, took the red line train with mom and dad to City Hall. And now, when he's not escaping for trips to be with dad at Green Bay, KJ practically lives with his grandmother.

"Little KJ is very outspoken, loud, and a joy to be around," Lisa Sykes said. "A curious boy who loves to be around his cousins. He so reminds me of Keifer."

At the time KJ was born Keifer was holding down a job with the Chicago Public Schools system, playing basketball and working rec centers with kids on the east side. He always had a way with kids, even when he was one. KJ crowned around dinnertime on Aug. 3, 2010, at Mount Sinai Medical Center. Until now, Sykes has never told the story of how he became a father, what the birth was like, the angst he went through and how scared and shocked he was by the process. He still gets frazzled thinking back to cutting KJ's umbilical cord, which he hesitantly failed to prune on first attempt, and only succeeded on the second snip under the loving demands of his father that he cut his son's cord.

College basketball rosters across the country are dotted with young dads. A few births have been by choice, but obviously many occur by accident. Dozens of programs were contacted for this story and asked if they had a player on their roster who was a father or a father-to-be. Most did. Fortunately, despite varied situations, some of which are depicted below, many have happy circumstances. They're cautionary stories but uplifting ones, too.

***

The best rebounder in college basketball, perhaps the most intimidating player in the sport, is a father. And like Dawson and Sykes, he's a pro prospect. Unlike Dawson and Sykes, he's married. Baylor's Rico Gathers, who's closing in on the Big 12's single-season record for rebounds, is beaming about his wife and life over the phone. This is a man who fondly recalls buying a $134 ring from Walmart the night before he proposed. In high school.

Bria Gathers still wears that ring.

The 21-year-old Bears power forward, a second cousin to the late Hank Gathers (who died 25 years to the day of this story's publishing), married his longtime girlfriend on June 10, 2013. The two met in middle school in Louisiana, and remained close friends until things turned romantic midway through high school. Gathers recalls now the way he won her over -- by attending her 16th birthday party and jokingly signing a basketball for her as a present.

Their relationship was so strong, their parents were OK with Bria moving to Waco, enrolling in a community college, and living in her own apartment at 18. Gathers saved up his scholarship checks ($400 per month) and Pell Grant money to help pay Bria's rent, which came to nearly $800/month. That's money which now goes toward feeding their baby boy, Ricardo Darnell Gathers Jr., who came into the world at 4:53 a.m. on June 13, 2014.

"I wouldn't say that it was planned but I definitely wouldn't say it was an accident," Gathers said of Bria's pregnancy, the climax of which included Rico taking four trips in one day to a Danny & Clyde's po'boy joint while Bria was in labor. He didn't sleep through the night, and in the darkest hour, their child was born. You can practically hear the smile through the phone as Gathers, who was wearing scrubs that didn't fit his 6-8, 275-pound frame, tells the story.

"It's not easy, for me, but the best thing I have going on for me right now is my wife," Gathers said. "She's the key to being married, to being a dad. Without her, I wouldn't have been as successful as I have been this year."

For now, the per diem pays for diapers. His college scholarship goes toward rent. His Pell Grant goes toward living needs, and the family receives government assistance in addition to food stamps and WIC, a national food stamps programs specifically for newborns and their mothers. Gathers, who's likely to return for his senior season, said his household of three is living off $15,000 per year.

***

Sykes, Dawson and Gathers all have teammates who are dads. Some of the scenarios are not ideal. Green Bay's Henry Uwadiae, a 6-foot-11 Nigerian-born sophomore, had a daughter born last summer. She lives more than 250 miles away, in Iowa, with her mother. Dawson's fellow father teammate is junior Bryn Forbes, who had a boy, Carter, born when Forbes played at Cleveland State. Gathers' teammate, Al Freeman? He's brand new to this game. Pictured below, there he is in the hospital with his girlfriend, Kylee, and his baby girl, Maddox, born three weeks ago -- smack dab in the middle of the season.

It's been an emotional journey for Freeman, who went out and bought a few pregnancy tests last summer, and then cried and hugged Kylee as they discovered they'd be parents. It wasn't a happy cry.

"We felt defeated," he said. "At first there was a lot of fear. We both were really scared. I can't describe how gracious God has been toward us. I have made past mistakes in my life, and God continues to make a way for us. We've had people tell us to not keep the baby, frankly."

Flash to Feb. 12, 2015, and Freeman's sleeping in the chair next to Kylee, awaiting his miracle. Suddenly he was holding ice chips and helping her breathe through the birth.

"And when the baby came out, man, it was so cool to be part of that atmosphere," Freeman said. "It was unbelievable ... it's really hard to explain ... I see my daughter come out to the world."

You scope college basketball, and the stories are everywhere. Some of them terrifying, like the hell and stress Rhode Island's T.J. Buchanan has endured all season. Buchanan's son, Terry Buchanan III, was born in November with a life-threatening condition. Doctors had to wait until the baby boy was just a little bit bigger, a little bit heavier, and a little bit older before they cut into his chest and sewed up the hole in his heart. Buchanan flew into Detroit after Sunday's Rams practice, then spent his Monday helplessly pacing around the University of Michigan Medical Center as his 18-week-old son underwent open-heart surgery.

On Tuesday morning, Buchanan got into a car with his father, aunt and uncle and drove nearly four hours to join his team in Dayton, Ohio. Buchanan, who leads URI in assists, played in Tuesday night's game against the Flyers, a vital one for Rhode Island's NCAA tourney at-large chances. The child's mother, Cecilia, and members of both parents' families crammed into a hospital room and glanced back and forth between watching a father on TV and keeping an eye on T.J. sleep with tubes and probes keeping him alive. Buchanan III is expected to stay in the hospital until at least this coming Sunday as the scar on his heart slowly starts to heal.

Like Buchanan, and others currently playing college hoops, BYU's Josh Sharp also became a father last fall. Sharp -- who's completed his Mormon mission obligations and is a 24-year-old senior on a team that in recent years has seen half its roster filled with married men -- saw little Jaycee Sharp come into the world 30 minutes after midnight on Oct. 1, 2014. Sharp and his wife, Jordan, planned the pregnancy. That wasn't the case with a 7-footer at Louisiana Tech named Joniah White.

"Over time, shock turned into excitement," White said of his world changing as a 17-year-old.

Joniah Jr. lives 260 miles away, in Grenada, Mississippi, while his dad is getting his sea legs under him as a freshman in Ruston, Louisiana. This arrangement was particularly worrisome and problematic recently, as the boy battled a bronchial infection. The little guy is now doing better and just turned three months old. After Saturday games, White drives east through the dark trails and over the Mississippi border to spend his Sundays with Joniah Jr. Memphis' Kedren Johnson can relate. He knows all about long drives on weekends to steal time with a child.

Like Freeman, Johnson's been a father for only a few weeks. Her name is Averyelle Dream. The mother, who Kedren has known since middle school, lives in Johnson's hometown of Lewisburg, Tennessee. The night before Averyelle was born, Johnson flew from Tulane back to Memphis, got in his car, immediately drove the three and a half hours to Franklin, Tennessee's Williamson Medical Center, and arrived around 3 a.m. He did not sleep overnight. Averyelle was born shortly after the sun came up.

"As soon as I could see her a little bit, I was really protective of her, just because she's so innocent and so helpless," Johnson said. "I immediately fell in love with her."

Johnson has two teammates, Markel Crawford and Trahson Burrell, who are fathers. Crawford's son lives in Memphis. Burrell's daughter, Alyson, is in Puerto Rico. Memphis also had a player, Dominic Magee, who initially transferred out of school earlier this season to be closer to his home in New Orleans to be with his young son. Magee is now enrolled at Grand Canyon University.

Even prominent teams, like Gonzaga, are touched by early fatherhood. Four-year starter Gary Bell Jr. hopes to have his son, Gary Bell III, in the stands come the first weekend of the NCAA Tournament in Seattle or Portland. Bell's boy already loves basketball. Every time dad gets home, son takes it right to the hoop.

Bell found out he was going to be a father when he returned to his phone following a workout. So many missed calls from his girlfriend. He felt shock, and immediately told his father. But mom? Of course he was worried about telling mom. Almost every player interviewed for this story was scared to tell mom.

"I didn't want to do it. I wanted to wait a few days," Bell said. "That was the hardest part, telling her, and the first thing she said was, 'She's going to be cute.'"

GB3 -- Bell's nickname for his son -- came out crying on Jan. 10, 2014, at 10 o'clock in the morning, 19 inches long and weighing six pounds.

"It was a surreal moment," Bell said of watching his son be born. "My stomach just dropped when I saw what he looked like. I was the first person to see him, which was pretty cool."

Like Bell at Gonzaga, Delaware's Kyle Anderson is a four-year starter. An uncle to six and the son of a farmer, Anderson grew up bailing hay in Newark, Illinois. He and his wife/high school sweetheart, Laura, are expecting. Anderson is banking on landing a pro contract overseas this spring or summer. The plan is for mother and child to pack up and go with.

"We want to young parents, to be young grandparents, all of that," Anderson said. "Looking back on my season, where did it go, and it's been a weird, weird year."

It's a boy, and they're down to two names with two months to go. May 14 is the due date.

***

The sport is now, has long been, and will continue to be populated by men who are fathers well before they are emotionally and financially ready for the task.

"It's always been this way, really, but off the record, it's demographics, number one, and popularity of basketball players today," one coach said. "More basketball players have the opportunity to have sex with more girls. And in addition to that, you've got a demographic of kids without fathers, maybe more irresponsible, who don't understand things at a young age and make mistakes earlier."

Dayton kicked two players off its roster earlier this season after a dorm-room theft forced Archie Miller's hand. One of those players already had a child, and the other had one on the way. SMU sophomore Keith Frazier, who's been suspended for the season, is a dad to a boy who's nearly 3 years old. Vital players at Cincinnati, Southeastern Louisiana and VCU (two players) are fathers. There are dads playing at Minnesota and UNC Wilmington. Rhode Island and Nevada. New Mexico and Mississippi State -- schools in the two states with the highest teen pregnancy rates in the country, feature players who are fathers.

For some, this is a touchy subject. Some schools turned down interview requests. One team has a father who's a leading scorer with a child who attends every home game but did not want to bring extra attention to the player or the program. One team has a player with two children born from two women three months apart. Another is dealing with a touch-and-go situation in regard to an abortion decision.

Another team lost a player in the middle of the night, without warning, because he was given an ultimatum by the child's mother. The coaching staff awoke to find out the player was more than a thousand miles away and quit the team without telling anyone. The player is now back at school, away from his child, but not on the team.

Mississippi State's Rick Ray is a coach with a lot of thoughts on this because he has a lot of players -- five of them -- in this situation. His players have brought their children over for playdates with Ray's son, who was born in 2013. In addition to having the second-highest teen pregnancy rate, Mississippi charts as the poorest state in the nation.

"Just because we're in college athletics, we try to separate ourselves from the rest of the society, and we just can't do that," Ray said. "You don't want to encourage your guys to have kids out of wedlock, but when it happens, you have to help them. The biggest help to me is my wife. She's going through the same thing these young ladies are going through. She's been a tremendous help to our players and our players' girlfriends. You'd be amazed at what these guys don't know about parenting. Simple things about how to feed your baby. We had guys on our team trying to feed their kids fast food. They just don't know. They think, 'that's what I eat, so that's what the baby should eat.' Simple things, like sleeping patterns. We've had them come in as a group and have my wife talking about child-rearing. Those are the things people have no idea what's going on behind closed doors with so many teams."

It's an intense situation for Ray and plenty of coaches who've become surrogate fathers in plenty of ways, this being a prominent one. Ray also said there are a lot of players who don't see their coaches as men who overcame hardship to be where they're at, so they're hesitant to approach or ask for help.

"My players say I don't understand, but I do understand," Ray said. "I tell them I grew up just as disenfranchised and poverty-stricken as they were. They say, 'You don't know what it's like to be on food stamps,' and I say, 'I've been through it.'"

There are major facets to these players' lives that are never seen, seldom known, but emotionally significant signposts toward personal growth and elemental struggle. Breakups, forced relationships, long-distance relationships, fractures between families, money -- these are stresses that, comparatively, make basketball seem so simple. Sykes and the mother of his child broke up when he was 17, when he left for college. He admits now it was a lot to go through.

"I was a freshman, already on the court, and trying to run a team, trying to learn, and learning how to be a dad and learn to be a college student," Sykes said. "It's the first time I had to do real school work. At Marshall, we were a basketball powerhouse, and it was a Chicago public school. Once my brother left, I went to school by myself. I was really on my own and traveling in Chicago for an hour each way each day. A lot of people don't see the world until college. I didn't learn that until I got to college."

At the time of Sykes' recruitment, Wardle (his coach), who became a dad at 26, could empathize. If anything, Sykes being a dad was a positive. In Wardle's eyes -- and having spoken to many coaches on this, many expressed similar sentiment -- here was a kid who was playing for something. Playing for two beating hearts.

"Most four-year players have a teammate at some point who is either having a child or has had a child," Illinois state coach Dan Muller, who's coached a few dads, said.

Mississippi State is the prime example. Trivante Bloodman is a 22-year-old senior guard from Harlem who's barely been able to sleep in the past week. Aubrey was born at 9:30 a.m. on Tuesday, Feb. 24. The next day, Bloodman played 18 minutes against Kentucky.

"I was speechless," he said. "I tried to hold back the tears. I thought I was going to pass out, but I stayed strong. Once she looked up at me, it was over after that."

Bloodman's long been saving for this. He says there's more than $5,000 of his own cash allotted toward parenthood. He graduates in two months.

***

Keifer Sykes Jr. does not know who James Sykes was. KJ wasn't even 2 when his grandfather died. Keifer frequently shows his son photos to remind him. It's very important to Keifer that KJ does not forget -- or rather, can easily remember -- who Keifer's father was.

"It's my job to do what my dad did and tell him who my dad was," Keifer said. "One time I asked him, and he didn't know. I was kind of sad. 'You don't know who this is?'"

Sykes' relationship with his son is the connection he carries from the one he had with his father, that connection he still feels, but one that inevitably dims with the passage of time.

"He's absolutely like his dad," Lisa Sykes said of her youngest. "He so reminds me of his dad. Sometimes when he's here and he's with KJ, I'm like, 'Oh my god, he's just like him'. He's going beyond the expectations of being there for his son. And whatever makes the mother happy, it's all about making the child happy. He makes sure, no matter what, he keeps a good relationship with his baby's mother. It's nothing else but about KJ."

KJ doesn't know just yet how his grandfather died -- or even what death is, or that people disappear from the world in abrupt and unfair ways. Keifer said that conversation will probably come in the next year or so. Because KJ wants to be a big boy really fast. Turning 5 will be the milestone. KJ just can't wait to be 5 years old.

Come August, Keifer will be three months removed from college. So long as his health is good, he'll have earned a pro contract by then. Eventually, Keifer will find himself back in Homewood, Illinois, standing over a plot where James Sykes eternally rests. He'll have his headstone then, and he'll have his son and grandson touching it.

A young man will ask his boy about his father.

Keifer will look at his son. KJ will look up to his dad.