The 2020 MLB season is roughly a month old and the trade deadline is less than two weeks away. Pretty crazy, isn't it? It's difficult to know which teams will buy and which teams will sell because the postseason is expanded and finances are a mess following the shutdown. I don't know what to expect. The deadline could be slow or it could be crazy, and neither would surprise me.

On the field, the 60-game season is roughly 40 percent complete and the "it's still early" excuse doesn't apply like it normally does a month into the season. Every game carries that much more importance in a short season. Last week we looked at Cleveland's poor outfield production, among other things. Now here are three other MLB trends to keep an eye on.

Bauer's sky-high spin rates

Four weeks into the new season, Reds right-hander Trevor Bauer is on the short list of the best pitchers in baseball. He's only made three starts because of the club's recent positive COVID-19 test, but, in those three starts, he's allowed just two runs in 19 1/3 innings. Bauer has struck out 32 and walked only four. He's been dominant.

Bauer, now 29 and an impending free agent, brought a career 4.04 ERA (109 ERA+) into the season, which is good but not truly great. He's flashed greatness, particularly in the second half of 2017 and before his leg injury in 2018. The overall consistency has been lacking though despite high-end stuff. Bauer's arsenal is among the most impressive in the sport.

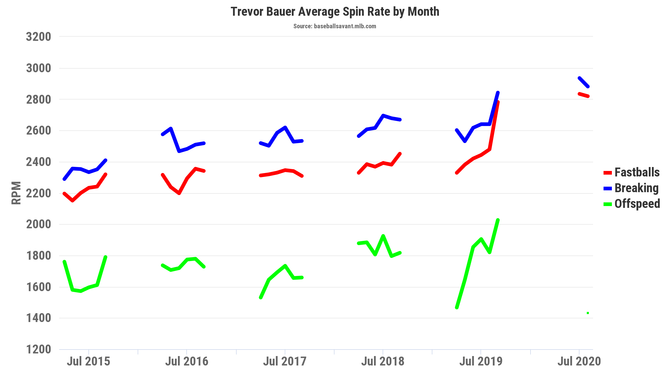

This season Bauer has changed his pitch mix a bit -- he's throwing more four-seam fastballs and cutters, and fewer curveballs and changeups -- and he's also added spin to his arsenal. Specifically, he's upped the spin rate on his fastballs and breaking balls while reducing spin on his offspeed stuff. Here's a graph:

Bauer has always had above-average spin and he's improved it further this year. You want high spin on fastballs and breaking balls because it helps generate swings and misses, and you want low spin on offspeed pitches because it creates tumbling action down and out of the zone. That's what Bauer is getting this season. High-spin fastballs and breaking balls and low-spin offspeed pitches.

As you can see in the graph, Bauer's fastball and breaking ball spin rate spike dates back to late last season, after he was traded to the Reds. He's taken it to another level this year. This is notable because Bauer once insinuated the Astros and former UCLA teammate Gerrit Cole were using foreign substances to improve spin rates. He also said this:

My fastball is about 2250 rpm on average. I know for a fact I can add 400 rpm to it by using pine tar. Look how much better I would be if I didn’t have morals... pic.twitter.com/o62kWkxWAy

— Trevor Bauer (@BauerOutage) April 11, 2018

In 2018, when that tweet was tweeted, Bauer's fastball had a 2,373 rpm average spin rate, which is quite good (the MLB average in 2018 was a 2,232 rpm spin rate on heaters). This season it's up to 2,824 rpm. Bauer said he knew for a fact he could add 400 rpm to his fastball by using pine tar and now it's up 451 rpm. Hmmm.

Pine tar and foreign substances are of course illegal but MLB leaves enforcement of those rules up to teams. Pitchers are only called on foreign substances when it's egregious and can't be ignored, like Michael Pineda having pine tar on his neck at Fenway Park in 2014. Red Sox then-manager John Farrell said something because he had too. It was too obvious.

There are pitchers on every team -- every single team -- that use a foreign substance to improve their grip and possibly their spin rate as well. Managers don't call opposing pitchers on it because they know their pitchers are doing it too, and that's not a can of worms anyone wants to open. Foreign substances are against the rules but are allowed via unspoken agreement.

The general belief is pitchers have a natural spin rate that can be improved only so much through training, similar to velocity. No matter how much I train, I will never throw 95 mph. No matter how much a pitcher with a 2,200 rpm fastball trains, he will never get it to 2,800 rpm naturally. A dramatic increase requires outside intervention (foreign substance, tackier baseball, etc.).

I see three possible explanations for Bauer's spin rate increase. One, he's cracked the code and found a way to improve his spin rate naturally. A legitimate possibility, to be sure. Two, he's in his free agent season and decided to skirt the rules to maximize his value in advance of his payday. MLB didn't make a big stink about the Astros in 2018. Why would they come after Bauer now?

And three, Bauer is trying to prove a point. He's performing this spin rate experiment to show a) you can in fact use a foreign substance to improve spin, and b) MLB has a double standard. Foreign substances are against the rules but everyone looks the other way. Bauer loves nothing if not attention and I wouldn't put it past him to expose how much foreign substances can change the playing field.

No matter the reason, Bauer's spin rates have spiked this season and it's having a tangible impact on his performance. Spin rate is not everything the same way velocity is not everything, but it is certainly important, and pitchers who have it and know how to use it are awfully tough to beat. We're seeing exactly that with Bauer in 2020.

Ruiz's power breakout

Back in April, we looked at three hitters who enjoyed a significant power spike late last year. Those late season power spikes can be easy to overlook but they do sometimes carry over to the following season. There is no better example than Jose Bautista, who hit 10 homers in his final 29 games in 2009 before his breakout 54-homer season in 2010.

Orioles third baseman Rio Ruiz had a power spike late last year. The 26-year-old managed only five home runs in his first 289 plate appearances. Ruiz spent about two weeks away from the team last July and August after his wife gave birth, and, when he rejoined the team, he socked seven homers in 124 plate appearances. 40 percent more homers in 43 percent fewer plate appearances.

The power output has carried over to 2020. Through 17 games and 75 plate appearances, Ruiz already has six home runs, half as many as he hit last season in only 18 percent of the plate appearances. He hit three homers in his first four games of the season and another three homers in a four-game span last week.

Ruiz was a highly regarded prospect not too long ago -- the Astros gave him a $1.85 million bonus as their fourth-round pick in 2012 -- and he went to the Braves in the Evan Gattis trade before landing with the Orioles in a Dec. 2018 waiver claim. Orioles GM Mike Elias drafted Ruiz when he was Houston's scouting director. It's no surprise Elias grabbed Ruiz on waivers when he was available.

As a prospect Ruiz always showed good pitch recognition and natural strength. "(He) has shown raw power that produces a steady stream of doubles and could generate more home runs as his body matures," wrote Baseball America in their 2018 scouting report. It wasn't until late 2019 that the power started to show up in games though, and O's manager Brandon Hyde has attributed that to a swing change.

Here's what Hyde told reporters, including the Baltimore Sun's Jon Meoli, recently:

"We talked a little about driving the ball, getting in his legs, but for me the underlying part of that conversation was get your confidence going," Hyde said. "We believe in you and we want you to go down there and start letting it eat with the bat. When he came back up, you saw more aggressive swings. He took that in the offseason and added some muscle and added some really good weight to a really athletic kid already. Now, he's stronger and swinging the bat with aggressiveness.

"He's just taken that to the next level right now. He's playing like he's an everyday third baseman in the American League East."

"Getting in his legs" and "swinging the bat with aggressiveness" are good baseball phrases but what do they look like, exactly? Here is 2019 Ruiz on the left and 2020 Ruiz on the right:

Ruiz has opened his stance and he's incorporated a bigger leg kick. The GIFs are synced at the moment the pitcher releases the ball, so you can see how much sooner Ruiz lifts his leg to begin his swing. He's getting himself into hitting position sooner. Also, he's loading his swing a little deeper. He coils and shows his number to the pitcher a tiny bit more before exploding forward.

The swing adjustments have not led to an increase in hard contact. In fact, Ruiz's average exit velocity (87.1 mph) and hard-hit rate (34.9 percent) are down from last season (88.4 mph and 36.5 percent). What has changed is his ability to elevate the ball. Ruiz has lowered his ground ball rate from 57.1 percent in 2018 to 44.7 percent in 2019 to 38.3 percent in 2020, and getting the ball airborne is a plus.

Already this season Ruiz has five barrels, which Statcast defines as "batted-ball events whose comparable hit types (in terms of exit velocity and launch angle) have led to a minimum .500 batting average and 1.500 slugging percentage." Last season Ruiz had eight. Eight in 285 batted balls last year and already five in 43 batted balls this year. His best contact is better, basically.

Ruiz is striking out a little too much (25.3 percent), leading to a low batting average (.215), but the power and the walks (10.7 percent) have made him approximately 21 percent better than league average offensively once adjusted for ballpark. Even if the Orioles are unable to stay in the postseason race all year, they can be happy knowing Ruiz is becoming a legitimate everyday big leaguer at third base.

"The more consistent I am with barreling balls and the positions I'm in, obviously I want to continue that, and continue the body of work I've had throughout the offseason and the shutdown and the course of the season," Ruiz told Meoli. "I look to continue that, obviously, and I'm hopeful the results can stay there."

Offense has returned

Two weeks into the new season folks within baseball and fans outside the game were asking the same question: where'd all the offense go? Offense was down the first few weeks of the season, so much so that the league batting average was hovering around .230 at one point. That was the lowest it had been since before the mound was lowered in 1969.

There was no firm explanation for the decline in offense but no shortage of theories. The ball is not quite as lively as last year, Rob Arthur of Baseball Prospectus has shown, so that's certainly a factor. Pitchers being ahead of hitters out of the shutdown? A possibility. Better defense? A greater variety of pitchers with expanded rosters? Poor approaches? All possible explanations.

Well, over the last week and a half, offense has come roaring back, and it's not just because more teams are getting a crack at the Red Sox's pitching staff (I kid, that was mean). Check out the MLB averages each week this season:

| Dates | AVG/OBP/SLG | BABIP | PA/HR | BB% | K% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

July 20-26 | .231/.314/.392 | .276 | 32.5 | 9.4 | 22.9 |

July 27 to Aug. 2 | .233/.314/.397 | .282 | 30.5 | 9.3 | 24.2 |

Aug. 3-9 | .227/.307/.395 | .270 | 28.8 | 9.2 | 24.1 |

Aug. 10-16 | .266/.335/.461 | .308 | 25.0 | 8.6 | 21.8 |

Teams are averaging 4.72 runs per game and 1.33 home runs per game this season, which is down a tick from last season (4.83 runs and 1.39 homers per game) but is much more normal looking than the league averages two weeks ago, which sat close to 4.00 runs per game and 1.10 homers per game. Those numbers were a significant drop from 2019.

This is such an unusual season that it'll be difficult (if not impossible) to determine what's real and what's small-sample-size noise. That's true on a player, a team, and a league level. I'm not sure anything we see this season will have predictive value going forward. That said, what's happening on the field is happening, and offense was down early. Now the hitters are starting to catch up.