Nine years ago, Grant Cohen sat in an East Village bar -- the kind of bar, he says, that stops charging once you make it past rounds six and seven -- gulping down cold beer to stave off the sticky summer air. A Yankees game blared in the background. At some point during those opening rounds, Cohen and his friends walked down a path that all sports fans have undoubtedly found themselves on.

They wanted to know if they -- a group of ordinary fans -- could collectively run a team better than general managers and coaches. But they didn't just want to own a team and call the shots like a Mark Cuban or Jerry Jones. They wanted to cede total control to their fan base, allowing the fans -- and only the fans -- to make in-game and offseason decisions.

Send Pedro Martinez out for the eighth inning or turn to the bullpen? Draft Jonny Flynn or Stephen Curry? Hand the ball to Marshawn Lynch or target Ricardo Lockette? Mortgage the future for the first-overall pick in the draft or take a chance on a developmental quarterback?

Unlike most conversations that begin after round two and end before round nine, the idea persisted.

"We just couldn't get it out of minds," says Cohen, now 34. "The idea."

The group turned the idea into a website for what they called Project Franchise. They investigated minor-league baseball teams, speaking with the commissioners of independent leagues across the country. The New York Times caught wind and put them on the map in 2008. That summer, Cohen traveled to Fort Worth, Texas, to scout an independent baseball team. There, the owner led a tour around LaGrave Field, where Jackie Robinson once played, almost immediately offering Cohen a chance to purchase the team. Cohen rebuffed the owner once he realized just how much debt he'd be inheriting.

Gradually, the idea faded. Life -- marriage, kids, careers -- happened. By 2011, the dream died. Cohen moved on, settling in the world of mobile advertising.

Almost five years later, in June of last year, a former minority owner in the Arena Football League (AFL), Sohrob Farudi, stumbled on an old New York Times article about something called Project Franchise. He did some Googling and connected with Cohen on LinkedIn. They spoke over the phone and hours later, met at a salad shop, along with Farudi's brother, in downtown Los Angeles. There, as Cohen sipped a sparkling water to cool off from the California heat, Farudi fed fresh oxygen into Cohen's idea.

Farudi, 39, helped turn Cohen's decade-old, bar-inspired idea into a reality -- a technology and sports company called Project FANchise.

Created by Farudi (CEO), Cohen (Digital), and four other co-founders, including former Chicago Bears defensive back Ray Austin, FANchise purchased a franchise in the Indoor Football League (IFL). That team, which will be based in Salt Lake City, is scheduled to make its debut at the beginning of the 2017 IFL season next February. The franchise will be entirely fan-run -- one fan will even serve as an official advisor and own a small piece of equity -- from selecting the coaches and final roster, to calling plays during games.

"We recognize that these are professionals who spent their whole careers doing this," Cohen says. "So they're better than me, but are they better than a hundred of me? A thousand of me?"

In the coming months, the first-ever truly fan-operated football team will answer that question.

*****

Born in 2008 as the result of a merger between the Intense Football League and the United Indoor Football Association, the IFL is a 10-team professional indoor league. Games feature eight-on-eight action on 50-yard fields. If the league sounds familiar, it's probably due to the presence of Kurt Warner's former AFL team, the Iowa Barnstormers, which joined the IFL this season and Dylan Favre, Brett Favre's nephew, who quarterbacks the Cedar Rapids Titans.

How about the show #thegoodguys put on last night? Recap last night's win with these TD highlights! https://t.co/yWp8YHRGTI

— Cedar Rapids Titans (@CRTitans) April 17, 2016

The idea behind FANchise is simple -- hand over the controls of a sports franchise to the fans -- but the plan behind the idea isn't. The reason FANchise's team will be based in Salt Lake City is entirely due to the fans, which narrowly selected Salt Lake City over Oklahoma City. Just like that process, fans will soon vote on the team's name. Fans will then choose the general manager, coaches, and roster. And when the Salt Lake City Dogs or Cats or Whatevers kick off their inaugural season in the IFL next February, fans will pick the plays in real time.

That's where the difficult part begins. For fans to call the plays in real time, they need to keep up with the speed of the game. And for fans, in some cases halfway around the world, to keep pace with a game inside the Maverik Center in Utah, the technology needs to do more than simply exist; it needs to operate without fail.

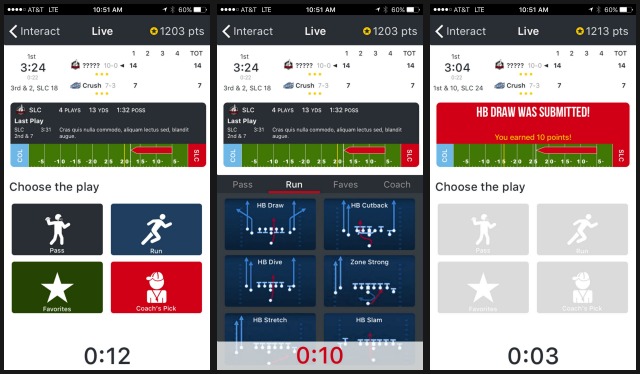

Over the coming months, FANchise will continue developing an app that will allow fans to tune in and call plays. Those plays will be presented in multiple choice format. As Cohen explains, imagine "WatchESPN meets Madden."

The app is still under construction, but FANchise provided CBSSports.com with an early glimpse at the design.

Once a play is selected, it'll be relayed to the coach on the sidelines, who will then communicate the call to the players. FANchise expects the professionals to obey the wishes of the fans, but they don't foresee a one-sided relationship between the two. To use an example, Farudi says they're "working on a deal" with an NFL scout, who would teach fans how to evaluate talent. The quarterback will also have the ability to audible out of a poor play.

In the beginning phases, play-calling duties will be more limited. During the first few games, fans might only select plays coming out of timeouts.

"Long term," Cohen says, "we totally envision getting the technology and fan-feed up to the point where we're actually calling all plays in original time."

The technology alone still doesn't solve other glaring issues. For instance, if 20,000 fans sign up, how are all those fans going to reach a consensus on one play in a matter of seconds?

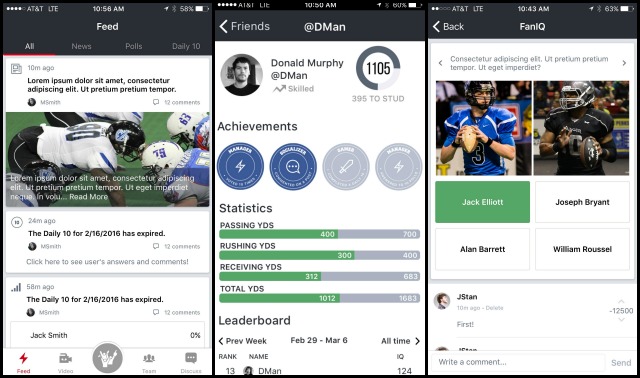

Fans will be divided into tiers, Cohen explains. Everyone who signs up starts as a rookie with the ability to vote for the team name, logo, and other non-competitive aspects. As a fan progresses upwards, he or she will have the ability to vote on more matters, eventually reaching play-calling status. Only the fans who reach the highest attainable level will have access to fourth-quarter play calling.

"We don't believe that all fans are equal," Cohen says. "This is not a true democracy."

The tier system is important, namely because it's intended to protect the integrity of the game. If all fans were equal, if they all had play-calling power, the risk of trolls hijacking a game would be too high.

So, to establish those tiers, fans will answer questions that test their general football knowledge.

"The plan right now is for every day at 3:55, you're getting a first-and-10 -- a series of 10 questions that will be tied to sports in general, but primarily football knowledge," Cohen says.

A question might be, "Who's the better Bears running back, Gale Sayers or Walter Payton?" And for the 55 percent of the fans that vote the same way, they'll receive points for siding with the majority. Another question might be drawn up by a coach, who will provide fans with the down and distance, and three different play-call options. Fans will then be asked to identify the best play for that given situation. Those who select the correct play will earn points.

FANchise calls this FanIQ.

In addition to those daily questions, fans can participate in other challenges. They might have the opportunity to duel with other fans, opting to risk some of their own points with the chance of securing even more if they win the head-to-head style game.

If the entire process -- from the Madden-style play calling to the daily questions and challenges -- sounds complicated, that's because it is. So, it's expected to undergo a process of trial and error.

There's another potential hiccup waiting to happen, but it has nothing to do with the technology. Instead, it relates to the human element. What kind of coach would want to serve as a glorified mime while the fans call the shots? Will players really embrace the idea or will they rebel against it?

Farudi and Cohen acknowledge both potential issues, with Farudi calling the coaching problem a "valid concern." When Farudi met with Tony Parrish, a former defensive back for the Bears, 49ers, and Cowboys, to discuss the idea, he says that's the top concern Parrish voiced. Farudi hopes, though, the fan-run nature of the team will attract talent rather than act as a repellent because of the expected exposure it'll give to players, some of whom are trying to get noticed by bigger leagues.

In an attempt to ease concerns, FANchise brought on advisers and investors with professional sports experience. Two of those advisers, Ahman Green, the Packers' all-time leading rusher, and Al Wilson, a former five-time Pro Bowl linebacker for the Broncos, admit that the level of success the fans see as play-callers might the biggest unknown in the operation.

Well, that and how the players respond to a fan-run offense and defense.

"You're always going to have frustration or doubt in the beginning of a big change," Green says. "This is going to be a big change for players around this league. From little league on in any sport, it's the coaches who make the plays calls, the quarterback calls the play in the huddle, and then you execute. And now you have somebody who wasn't at practice, someone who wasn't in the locker room, who will have the opportunity (to call plays)."

Already, Cohen says, thousands are signing up for that very opportunity, including fans in Finland, Africa, the UK, and "all over."

*****

Farudi claims he doesn't have that one sitting-in-a-bar type of moment Cohen had. And he's mostly right.

His professional background prior to FANchise's birth doesn't exactly look like a roadmap to owning a football team. Farudi and his brother started a company in 2004 called Flipswap, which basically provided a platform to trade in cell phones. In 2011, they sold the company. From there, he became a CEO of a mobile web analytics company. He started a digital agency, "dabbling" in other business ideas.

Again, Farudi was only mostly right -- because that dabbling led to his involvement with medical marijuana in Las Vegas, which led to a trip out to Vegas to apply for licenses, which led to a meeting with Vince Neil's friends, which led to Farudi becoming a minority owner of the Arena Football League (AFL) team that Neil, the former Motley Crue frontman, owned in Las Vegas.

At that point in time, the fall of 2014, Farudi had never met Cohen. Still, Farudi had an idea -- the same one that Cohen and his friends had conjured up in that dingy New York City bar. He wanted to test a fan-run concept on the Las Vegas Outlaws.

Before his idea could gain traction in the AFL, the Outlaws disbanded after the 2015 season due to financial reasons. Neil pinned the failure on Farudi, who denied Neil's claims. Farudi is currently suing Neil for "fraud, conversion, unjust enrichment, conspiracy and defamation," according to Courthouse News Service.

Still, that experience opened the door for Farudi. Due to his ties with the owner of the former Spokane-based AFL team, which recently relocated to the IFL, Farudi considered testing his idea in IFL waters. Just as importantly, it gave him some real insight into running a sports franchise, even if it ended in a Hindenburgian disaster.

When the team folded, Farudi continued researching the idea and assembling a team of founders and advisors, the latter of which includes former players like Green and Wilson.

"I just felt like this was the evolution of fantasy football when I first thought about it," Wilson says. "I just thought it was a genius idea."

Andy Dolich, who brings 40 years of experience as an executive for organizations like the Oakland A's, Memphis Grizzlies, Golden State Warriors, and San Francisco 49ers, also joined as an advisor.

"I don't just see this as something that will just be successful in Salt Lake City," Dolich says. "Think about people in a pub in Ireland or the UK or any other place arguing about an upcoming game in the Premier League. ... That's what people love about sports. It's so addictive these days and there's so many ways to consume it because of mobile devices. Everybody is their own team owner, president, general manager, director of player personnel, head of marketing, and CEO in their own minds, which is fine -- that's exactly what we want."

In June of last year, Farudi connected with Cohen and invited him to come onboard, due to his "unique background in the mobile ad space," which is something Farudi and his team lacked.

Though Project Franchise died in 2011 and Cohen moved on with his life, those five years that he spent in mobile advertising paid off just as much as the beer-fueled conversation a decade ago. If not for that period in his life -- the idea's hiatus -- Cohen's qualifications to help run FANchise wouldn't have existed.

Cohen refers to that five-year window as "serendipitous timing." In simpler terms, those five years were entirely necessary. His idea began in a bar over bottomless beers, sure, but nearly every sports fan on the planet has broached that topic at some point. Until now, no one else has created a fan-run football team.

*****

To be clear, FANchise isn't limiting their scope to Salt Lake City.

"We're definitely not centered on one team. ... Our goal is to build a platform that can be licensed out to other teams, to other sports," Farudi says. "Longer term, we'd love for there to be a fully fan-run league."

To do that, the team will need to establish itself and succeed in its local market first to prove that the idea, at its very core, works. Like every other team, they need to win to keep fans interested.

"Season one, we don't have to win a lot of games and it'll still be exciting," Farudi says. "But looking at season two and season three, if this team's constantly a cellar dweller, that's not going to be acceptable."

Then, they need to make money.

As Cohen explains, 40 percent of the revenue for a traditional team comes from sponsorship, 40 percent is due to ticket sales, and 20 percent is rooted in merchandise, concessions, and parking. FANchise believes they'll follow a similar model and Cohen notes that the costs of running their team won't be much higher than a regular team.

They also believe they're set up to out-earn standard operations. For starters, Cohen says their app will serve as an additional revenue stream, as premium purchasing through the app will be available. Fans won't be able to buy power, but they will be able to purchase additional games and opportunities to earn influence. Plus, they're theorizing their hyper-engaged fan base will buy more tickets and merchandise, while also allowing for more sponsorship opportunities.

Even if they struggle in the early years, which is a real possibility given all of the unknowns, Farudi is confident they can "weather the storm." One reason they chose to buy an IFL team is the financial structure.

"Even the worst performing teams in the league don't lose enough money to bankrupt people who have done fairly well in their lives. In the AFL, if you don't do things right, you're losing multiple, multiple millions of dollars a year," Farudi says. "In the IFL, you don't even sniff a million-dollar loss -- or maybe even half of that -- even if you're not doing well. It's a much more palatable loss than it would be in another league."

If FANchise's team survives the trial and error phase, and catches on in Utah, the idea could, in theory, spread throughout the league -- and beyond.

"Obviously, if there's some success (in Salt Lake City), I can definitely see our teams in our league -- and other teams around the nation in professional sports -- adopting some of the aspects they incorporate," says IFL commissioner Michael Allshouse.

This past September, the six co-founders formally pitched the idea to Allshouse and the ownership groups in a Las Vegas conference room. One question the IFL owners asked them still sticks in Farudi's mind. As Farudi and the other five co-founders exited the conference room and headed to a nearby bar, where a GOP debate flashed on the TV screens, that question was all Farudi could think about, because it's what gave him the belief they would gain approval from the IFL to go ahead with their vision.

"We had two ownership groups that asked the same question, which was, 'So if this is successful, are you guys going to license the technology or let the rest of the members of league use the technology?'" Farudi recalls. "And our answer was a resounding absolutely."

So, if the technology works, if the fans show sustained interest, if the folks in Salt Lake City show up and, if the team wins, then -- and only then -- FANchise will have a chance to become more than just a company that owns one IFL team. As Dolich says, they'll be "casting a pebble in a pond in Salt Lake to show that this is a viable concept and that it is not something that was just dreamed up in somebody's garage two weeks ago."

The margins are slim. There are a millions ifs. All it takes is one of those ifs to go wrong for the idea to flip on its head. Success can't even be predicted because, well, nobody's even tried this before, which is why one of FANchise's most asked questions is, unsurprisingly, "Is this real?"

"We're in," Cohen says. "If it doesn't happen, a lot of people are going to lose a lot of money."