When the Indianapolis Colts narrowly fell to the Buffalo Bills in the opening round of the playoffs earlier this month, Nick Sirianni found himself flush with rare free time. An offensive coordinator with no more offense to coordinate, the Colts' 39-year-old staffer did what anyone in his situation would do: He packed up the family, took one last breath of mid-30s Midwest air, and trekked to Fort Lauderdale. Little did he know, days later, that he'd be summoned right back to chillier whereabouts ... for the biggest opportunity of his life.

Nick Sirianni never interviewed for a head coaching job before this January. The Cleveland Browns sniffed around in 2019, after his first and only season as a coordinator, but never formalized talks. This offseason, with seven vacancies around the league, it was more of the same. Fort Lauderdale, it turns out, was going to be a true vacation. Some much-needed family time before another go-round with the Colts in 2021. Until his agent called. The Philadelphia Eagles were on the other line. They wanted to talk.

Eagles owner Jeffrey Lurie was stationed in West Palm Beach, about 45 miles north. A week earlier, he'd parted ways with Doug Pederson, the first and only coach to ever bring him -- and all of Philadelphia -- a Super Bowl title. Lurie and his team had already spoken with upwards of 10 potential replacements by that point. Four seasons after winning it all, the Eagles craved fresh leadership. They'd declined in three straight years. Their star quarterback had fallen off the map. Their magic, once the talk of the NFL, had vanished. Frankly, they didn't just need a new coach. They needed hope.

And that's when they found Nick.

With the family's blessing, Sirianni drove up to West Palm and spent a day fielding the Eagles' questions and firing back. That night, he called Jay, one of his two older brothers, and told him he thought the exchange went really well. The Eagles agreed, contacting him shortly afterward for a second sit-down the next day. By Thursday, two days into his official visit, word started to get around: Philadelphia had found its next head coach.

The Mount Union connection

The offices of Larimer Athletic Complex, home to the University of Toledo Rockets, were one of the first places to erupt in celebration. A handful of Rockets staffers, including defensive coordinator Vince Kehres, hail from Mount Union, a private university and Division III powerhouse tucked in northeast Ohio. Sirianni comes from the same school. In fact, Kehres was on staff at Mount Union when Sirianni both played and coached there.

"When Nick was still in high school, one of my college roommates was his brother," Kehres says. "We would go back to their hometown and hang out there in Jamestown (New York). We'd watch Nick play basketball. We actually went over to the gym and scrimmaged with their basketball team on Saturday mornings. And then, my first experience with recruiting, Nick was one of the guys that I was the recruiter for. We spent a lot of time on the phone."

At the time, Sirianni was a tall, slender, teenage wide receiver coming out of small-town Southwestern Central, where his dad, Fran, coached high school football for more than 40 years. It didn't take long for Kehres to notice his work ethic. A year into college at Mount Union, which racked up 13 national championships between 1993-2017, Sirianni suffered a potentially career-ending leg injury.

"I remember hearing that this was really serious," Kehres says. "And I can remember Nick really wanted to get back. I was in charge of the weight room, so Saturdays, I'd be kind of cleaning up at the end of the day, around 3 or 4 on a Saturday afternoon. It was pretty quiet by then. And Nick would be in there working on releases against a dummy, whatever piece of equipment he could find. Just on his own. That stuck with me over time."

It doesn't surprise Kehres that Sirianni has made such a rapid ascent to an NFL head coaching job. After the latter graduated, he joined Kehres on staff at Mount Union, then coached by Kehres' father, Larry. In two years as a defensive backs coach, working under Vince at defensive coordinator, Sirianni focused on cornerbacks but ended up resonating with the whole team, even in his early 20s.

"In this profession, sometimes it's easy to try to be something other than yourself," Kehres says. "To not be 100 percent authentic all the time. And he was also coming in at about the same age as some of these players, guys he had just played with. But he was very consistent with his demeanor. He'd be considered a players' coach. And he also had really good relationships with his coaches."

In Mount Union's locker room, there's a sign that lists the team's core values: Work, commitment, loyalty and hope. Kehres can't recall a time Sirianni didn't embody them. It was a pleasant surprise, however, when Sirianni confirmed, on the night of the Eagles' job offer, that those Mount Union roots remain as firm as ever. He shot his old friend a text of congratulations, figuring the message would be lost in the shuffle of perhaps the busiest day of his life.

"He responded right away," Kehres says. "He was really grateful." Not only that, but the newest Eagles coach also told Kehres that he "used a lot of Mount Union things in his interview." The Eagles, remember, were desperate for hope. Who could've predicted they would've drawn it from an old D-III school, via an alumnus who'd passed through its hallways nearly two decades earlier?

An entire family of Eagles

Truth be told, Sirianni has always been a reflection of his upbringing. Just days into his official Philadelphia tenure, his family's football ties have already been well documented. His dad, Fran, is a local legend, his name gracing his high school's athletic complex. His brother Jay spent 12 years coaching the same Southwestern Central team, winning two state titles. His oldest brother, Mike, has coached Washington & Jefferson College, in Pennsylvania, since 2003, racking up a 156-36 career record -- good enough for the second-best mark among all NCAA coaches with at least five years of experience.

Before Nick stepped foot on Mount Union grass as a receiver and coach, Mike did the same, catching passes for the college's first national-title team in 1993, then spending 1996-1997 as an assistant. But big brother's steps weren't the only thing Sirianni followed faithfully growing up. There was also the instruction of Fran and Amy, his mother, in their small-town western New York home.

"This is a strong family," says Larry Kehres, who coached Mount Union from 1986-2012, overseeing Sirianni as both a player and assistant. "They were raised strong Catholics, attending Mass every week. Whether those boys wanted to go to basketball or whatever, their mom had 'em there. If Nick goofed up in life, it would be his fault, all by himself. He brings so much from the family -- character, poise, the ability to handle pressure, to say the right things."

It's no wonder that old friends, family and acquaintances across Ohio are ready to cast aside longtime NFL allegiances for Philly. They didn't just grow up with Nick. They grew up with his whole clan. Coached with them. Played with them. Lived with them. When the Eagles invited Nick to lead their team, it was as if they summoned his entire community in the process.

"I've been a Steelers fan pretty much my whole life," says Vince Kehres. "Jack Lambert had a football camp at Mount Union when I was real young, so I was hooked from there. But, yeah, I'm gonna be an Eagles fan." His dad, Larry, who's long been loyal to the Browns, takes it a step further: "We're all gonna be rooting for the Eagles. Every time they're playing."

The man for the job

Beneath all the intrigue of a fresh, first-time head coach embracing the City of Brotherly Love, and vice-versa, is the harsh reality of the Eagles' situation. Under normal circumstances, you aren't even considering a new coach less than three calendar years after hoisting the Lombardi Trophy. Dysfunction has been increasingly widespread in the organization. Pederson was a well-liked, aw-shucks figurehead whose players never quit on him, but his offense got more predictable and less creative as the years went on. Even more concerning: Left in the wake of his abrupt ouster are a star quarterback who both regressed and seemingly resented team leadership in 2020, as well as a general manager whose title-winning roster assembly looks more and more like a mirage.

Sirianni, in his first crack at running a team, will be charged with fixing or replacing said QB, navigating said GM's three-year pileup of expensive and unreliable contracts, and somehow living up to team owner Jeffrey Lurie's standard of restored Super Bowl contention. The task will be tall -- probably even taller than the one Pederson inherited in 2016, when Lurie and Co. were more interested in reversing course from Chip Kelly's alienating, robotic approach rather than truly unearthing their next Andy Reid.

Sirianni's got a couple things going for him: For one, Lurie's own judgment. Of his four hires since buying the team in 1994, all four have made the postseason, three have won at least one playoff game, and two have won Coach of the Year. The two times he's plucked from relative anonymity, hiring Reid and Pederson despite both having no prior play-calling experience, he's overseen some of the best football in franchise history.

Then there's Sirianni himself. Thirteen years younger than Pederson, his lean frame and stubble beard guarantee he'd pass through the streets of Philly unnoticed by most. But his resume reads like the prototypical candidate for the moment: An emerging offensive strategist, hand-picked by Colts coach Frank Reich a year after Reich oversaw QB Carson Wentz's MVP-caliber breakout and helped the Eagles win it all, and who just happened to oversee career years from his starters as the Chargers' wide receivers coach (2014-2017), and who survived two different teams' head coaching changes along the way.

Even better, the people who know him -- the people who've seen him coach since his earliest days on the sideline -- insist he's got the temperament for an NFL setting. Even a potentially volatile one.

"Nick is gonna be good when there's an issue," says Larry Kehres, whose 30+ year run as Mount Union coach and athletic director included oversight of alumni like coveted Iowa State coach Matt Campbell and 11-year NFL veteran Pierre Garcon. "A health issue or personal issue or family issue, it doesn't matter. One time he sent me a text about a young guy on one of the pro teams he was working with -- a guy who'd suffered a series of injuries. He told me how discouraged this guy was, recalling how he needed the same kind of support when he was young. He understands. He's prepared for this job."

Kehres' son, Vince, echoes the sentiment: "Nick is good with people. He's had some really good mentors. He'll connect with his guys, particularly the ones he's gonna be most hands-on with in the meeting rooms and the practice fields." (Vince makes it clear that Sirianni is no pushover, either, using the QB situation as an example: "When he decides, that'll be the guy that's best for the Philadelphia Eagles.")

His dad, Larry, thinks a hopeful comparison for Sirianni is first-year Browns coach Kevin Stefanski, who went 11-5 to lead Cleveland to its first playoff berth in 18 years this season. Stefanski also inherited a polarizing but highly drafted QB and stemmed from a family-oriented background. "You look at these two, they've got the beards, they've got the 'i' at the end of their names," the elder Kehres laughs. "But I really do think there's a similarity there. They're both guys who came up on that side of the ball, who took in a lot. They were around a lot of veteran coaches."

'Hire him right now!'

If there's one thing that sets Sirianni apart, either from Stefanski or Pederson, it's what Vince Kehres calls "a little bit of a fiery side" -- an "ability to create a sense of urgency on the practice field." That's not to say most NFL head coaches, Pederson and Stefanski included, totally lack it. But there's a reason Frank Reich's wife once described Nick as "the antithesis to my husband," who's known for his even-keeled, almost laid-back approach, calling the former Colts up-and-comer a "really overzealous, crazy, young coach."

For all his every-man appeal and homegrown roots and personable touch, the guy's got flare. Which, if we're being honest, is something else the Eagles have sorely lacked since the Super Bowl. For every quiet weight-room rehab session, in which Sirianni kept to himself to fight for his own football dreams, there were just as many public bursts of exuberance -- unmistakable displays of a lifelong heart for the game. Cliche as it may sound, his colleagues have the stories to back it up.

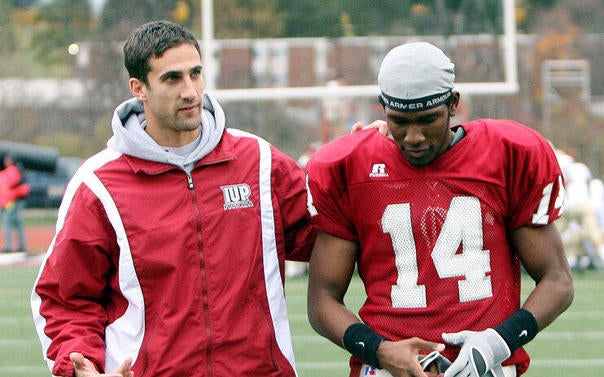

In 2006, just two years out of college and two seasons into his coaching career, Sirianni interviewed for an open WRs coach position with Indiana University of Pennsylvania (IUP), about an hour east of Pittsburgh. Hungry to return to his natural side of the ball, not to mention inch closer to an NFL job, he practically bounced off the walls.

"I had been here 11 years before Nick interviewed," says IUP coach Paul Tortorella, the defensive coordinator at the time. "I remember telling a couple of assistants, 'This is a no-brainer. Hire him right now before he leaves!'"

Not long afterward, IUP was visiting northwestern Pennsylvania for a game against Edinboro University. Sirianni was working out of the press box, through the phones. But at some point during the game, the phones stopped working.

"So they told him to come down to the sideline," Tortorella recalls. "During a big play that we had, I see this guy running down the numbers near our sideline, and then I see an official throw a flag. The flag ended up being on Nick because he was on the field!"

A little mistake in a forgotten game, but an immortal memory for Tortorella, who could see bright as day that this kid just wanted to do his job, no matter the cost. This kid wanted to coach. This kid wanted to win.

A year later, that kid went from IUP's Division II field to the sidelines of Arrowhead Stadium, connected through a mutual friend of then-Kansas City Chiefs coach Todd Haley for his first job in the pros. And he was off to the races. The sands of Fort Lauderdale -- and the phone call from Philadelphia -- would be waiting.