This is the second of two posts in our Super Bowl 49 Key Matchups series. The previous post, on Seattle's run game against the New England defensive front, ran on Sunday.

Seattle has the NFL's best defense, and it also might be the simplest. For the large majority of the time, the Seahawks sit in Cover-3 and just dare teams to out-execute them. Most simply can't do it. The sheer amount of talent on Seattle's defense, utilized in a system that is tailored perfectly to their skill sets, is just too overwhelming. Seattle's secondary covers too well and its defensive line gets too much pressure.

What is Cover-3, anyway? In the most basic sense, it's a zone coverage scheme that divides the field into thirds, with each outside cornerback responsible for the deep third on one side of the field and the free safety patrolling the deep middle. The underneath zones (flat, hook-to-curl) are covered by the linebackers and strong safety, or the nickel and dime corners when sub packages come in. There are different variations (explained in-depth by former NFL player Matt Bowen here), but that's the basic gist.

(You can subscribe to the Eye on Football Podcast -- live from the Super Bowl all week! -- via iTunes right here.)

Seattle's version of Cover-3 sees Richard Sherman control the deep third on the offense's right side of the field, Byron Maxwell on the offense's left and Earl Thomas in the middle. They very rarely stray from that alignment. Sherman lined up to the offense's right on 91.3 percent of his snaps this season, according to ESPN, and he's lined up to the offense's left for only 90 defensive snaps (out of 2,839) in his career.

Seattle covers all three areas of the field equally well in a general sense -- they ranked third overall in pass DVOA this season; fifth when facing throws to the left, eighth against throws to the middle and fourth on throws to the right. The Seahawks don't care how you shuffle your alignments. Sherman plays on his side of the field and Maxwell plays opposite him. If you want to have your best wideout stick to one side of the field for the entire game, so be it.

In Seattle's Week 1 game against the Green Bay Packers, Aaron Rodgers famously avoided throwing at Sherman at all. The Packers sent Jarrett Boykin to Sherman's side for almost every play and basically pretended the right side of the field didn't exist. Rodgers threw only three of his 32 passes to the right side of the field in that game, less than 10 percent. Meanwhile, 11 of his 32 passes went to the left side of the field. That was a massive shift from his pass distribution for the rest of the season, which saw him throw more passes to the right (26.8 percent) than to the left (23.0 percent). Rather unsurprisingly, that Week 1 contest wound up being one of Rodgers' worst games of the season.

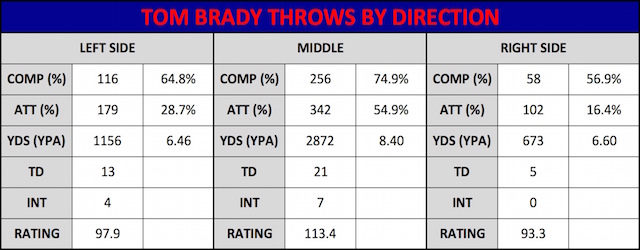

The Patriots won't have to make nearly as drastic an offensive shift if they wish to avoid throwing Sherman's way. Check out the distribution of Tom Brady's passes this season, courtesy of Pro Football Focus.

Brady threw to the left side of the field -- where Maxwell will be lined up -- far more often (28.7 percent of the time) this season than he did to the right (16.4 percent). He also completed a far greater percentage of his passes (64.8 percent to 56.9 percent) when throwing to his left, and though he was intercepted more, his passes turned into touchdowns at a significantly higher rate when throwing that way (7.3 percent) than when he threw to the right side of the field (4.9 percent). It's already a natural New England strength to go away from Sherman, and that likely won't change much on Sunday.

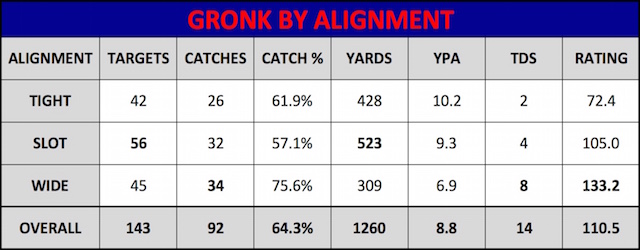

Brady's favorite target when throwing left is unsurprisingly tight end Rob Gronkowski. Gronk had 38 catches for 532 yards and 10 touchdowns on throws to the left side of the field alone. Brady and the Pats love to split Gronk out wide near the goal line to get him matched up one-on-one with a corner or a safety, most of whom are not nearly big or strong enough to handle him.

The result of plays like this is almost never favorable for the defense. Gronk is actually more effective when split out wide than when he's lined up in line as a tight end or in the slot.

The above numbers combine Gronkowski's regular season and postseason production to show where he's done the most damage. He has more catches when lined up wide than in any other alignment, and a higher catch rate as well. Those receptions average fewer yards, likely owing to the fact that it's a set the Patriots tend to break out near the goal line more often than anywhere else, like in the screenshot above. If Gronkowski is able to get matched up one-on-one with most defensive backs near the goal line, the battle is already over.

The Seahawks defensive backs aren't like most other defensive backs, though. The defining characteristic of the Legion of Boom (other than their spectacular play and willingness to talk about it) is their size. Earl Thomas, possibly the best safety in football, is the smallest LOB member at 5-10, 202 pounds. Nickel corner Jeremy Lane is 6-0, 190 pounds. Byron Maxwell is 6-1, 207, while Richard Sherman is 6-3, 195 and Kam Chancellor is the biggest safety in the league at 6-3, 232 pounds.

Gronkowski still has a size advantage over all of them, of course, but he doesn't dwarf the Seattle defensive backfield like he does most others. The Seahawks can stick Chancellor on Gronkowski when he splits out near the goal line and feel reasonably comfortable that he won't just get physically dominated. Or they could treat Gronkowski as they did Andrew Quarless in the NFC title game and line up linebacker K.J. Wright across from him, having Wright slant his body with inside leverage to completely take away the option of a slant. That would force Brady and Gronkowski to go to the fade, a much lower percentage pass. Obviously, though, that is easier said than done.

In any event, the Seahawks actually struggled to cover tight ends more than they did any other receiving option this season. While Seattle ranked fourth in pass defense DVOA against No. 1 receivers, sixth against No. 2 wideouts and fourth against the slot, they were only 18th against both tight ends and running backs. Gronkowski working seam routes or digs in the middle of the field, behind the linebackers and in front of Thomas, is something that could work very well for the Patriots on Sunday.

Similarly, while he's been marginalized in recent weeks in favor of LeGarrette Blount, Shane Vereen could be very useful both out of the backfield and split out wide in the Super Bowl. Vereen is an excellent receiving back, and it's worth exploring how the Seahawks wish to match up with him when he lines up wide to either side or motions out of the backfield. If they use a linebacker rather than one of their corners, it's a matchup that could be exploited. Vereen has busted open for big plays down the field multiple times this season, including once against the Ravens a few weeks ago. Had Brady not underthrown the ball, it would have been a touchdown.

One of the keys to forcing Brady into bad throws like that is getting pressure in his face. Brady was pressured on only 27.3 percent of his throws this season, the sixth-lowest figure in the league. When opposing teams did manage to get pressure on him, though, his numbers collapsed, and that's a trend that goes back a few years now. Judging by his quarterback rating, Brady turns from Aaron Rodgers into Heath Shuler when opponents put pressure on him.

The Seahawks have the goods to bring pressure with the best of them. Michael Bennett and Cliff Avril are possibly the best duo of pass-rushing defensive ends in the league, and though Jordan Hill is out with an injury, guys like Bruce Irvin, Kevin Williams and O'Brien Schofield can help bring supplemental pressure from the edge and inside.

Of course, Brady is one of the NFL's best at countering pressure by getting rid of the ball quickly before it has a chance to hit home. He held the ball for an average of 2.39 seconds before throwing this season, second-fastest in the NFL to only Peyton Manning. When holding the ball for 2.5 seconds or less before delivering, Brady was unstoppable, completing 70.7 percent of his passes and registering a 101.1 quarterback rating. If he had to hold the ball longer than that, though, his completion percentage dropped down to 50.0 percent and his quarterback rating dipped to 89.3.

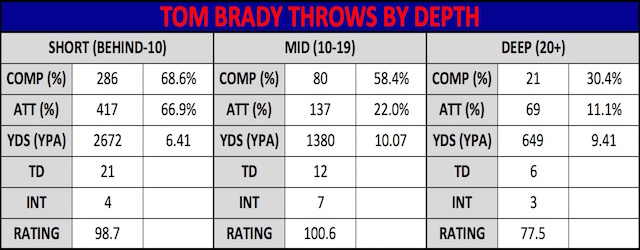

Holding the ball in the pocket for a long period of time is something a quarterback usually does if a.) his primary and secondary reads are well-covered, a distinct possibility against Seattle; or b.) he's loading up to throw it deep, which is something Brady rarely does. Only 10.3 percent of Brady's passes this season were thrown 20 or more yards down the field, a lower percentage than 20 other quarterbacks. He was not especially effective on those throws, either, completing only 21 of 69 such passes.

He's much better when throwing to targets at short (under 10 yards) or medium (10-19 yards) depth, and he throws short passes more than twice as often as he does to targets deeper than that.

Those short routes are where Brady loves to target receiver Julian Edelman. Because of Edelman's stature, he's not all that much of a deep threat, but his speed and quickness in tight spaces allows him to get open quickly in locations where Brady can easily complete his throws.

Though those passes might not move the chains every time, they're extremely helpful in maintaining possession and working the clock because they're also far easier to complete than passes targeted down the field. Edelman had the eighth-best catch rate (receptions/targets) in the NFL among the 110 receivers who played at least 25 percent of their team's snaps this season, but he also averaged only the 92nd-most yards per reception of those same players.

Because Edelman is typically shorter and lower to the ground than the player covering him, he's able to get in and out of his breaks faster and thus provide a window for Brady to deliver the ball. That should prove especially helpful against the Seattle secondary, which, again, is filled with tall defensive backs. Still, Seattle was excellent against short passes this year, ranking fourth in pass defense DVOA on throws targeted fewer than 10 yards down the field. It helps that they are great tacklers, but their aggressive press coverage is also a major factor because that delays receivers from getting open quickly.

To aid Edelman in that area, the Patriots would be wise to borrow a strategy the Ravens used in the divisional round game they played against the Pats. In the first half, the Ravens continually used tight, stacked formations and motion to get Steve Smith -- another short receiver -- open against Darrelle Revis.

Lining up in tight splits will accomplish two goals: a.) it will remove Sherman and Maxwell from their comfort zones on the wide side of the field; b.) it will give Edelman more room to break to the outside and thus more room for Brady to miss wide and incomplete rather than inside and intercepted. Using motion will allow Edelman to get off the line of scrimmage without getting jammed immediately. That all plays to New England's strengths while minimizing Seattle's biggest advantages.

This is a chess match that features one of the best precision passers in the league and the defense that provides the smallest windows through which to throw. Each side has matchup advantages and disadvantages, and whichever team is able to maximize their personnel and scheme at the expense of the other seems likely to come away the winner.