Nearly two months into Major League Baseball's owner-imposed lockout, the league and the MLB Players Association continue to swap economic proposals. Last week, MLB said it was open to a union proposal that would award bonuses to the 30 pre-arbitration players with the highest Wins Above Replacement (WAR) totals. The sides diverged in how much money to earmark for said bonuses: the league offered a $10 million bonus pool, whereas the union sought more than $100 million.

While it's unclear if the proposal will make it into the final Collective Bargaining Agreement, it's easy to understand why both sides would be for it. The league would be spared from making a more substantive change to the compensation, like shortening the runway to arbitration or free agency. The union, meanwhile, would deliver on its promise to funnel more money toward well-performing youngsters who, under the current system, are locked in to league-minimum wages.

Each side having reason to push for the implementation of the WAR bonus system does not necessarily make it a good policy, however. Rather, there are legitimate reasons to be wary of the proposed system. Allow us to tackle three key issues.

1. The WAR lords want no part

Anyone familiar with WAR knows that it's a framework in addition to being a metric. That's why Baseball-Reference, FanGraphs, and Baseball Prospectus all have their own editions of WAR, complete with different inputs and weighing systems that result in different outputs. It isn't difficult to find players who the three versions of the metric disagree on. Yet it appears that they're in agreement in disliking this proposal.

"Having [WARP] used to determine player compensation is an uncomfortable thing," BP's editor in chief Craig Goldstein told Matt Martell of Sports Illustrated. "We're doing the best we can, but I think anyone who hosts a metric like that will tell you there are issues with them. There are generalizations; there are weak spots. That's part of the reason why there are multiple versions of these things. They take different philosophical approaches."

Looks up "hoisted on his own petard." I don't speak for @fangraphs or @baseballpro, but I can't imagine they are any more excited about this idea than we are. https://t.co/uheOB1b85z

— Sean Forman (@sean_forman) January 25, 2022

Sean Forman, the overseer of Baseball Reference, laid out on Twitter why he wouldn't want his site's version of WAR used by the league and the union. Some of his points of contention include the ever-changing nature of the metric (based on data cleaning and methodology tweaks) and the unrequested and undesired responsibility that comes with dictating which players will receive additional millions and which won't.

MLB and the MLBPA might agree to create their own version of WAR for this purpose, but even that has its potential issues. Just ask … well, the people pushing back against their own versions of the metric being used to decide such things.

2. Won't curb service-time manipulation

Another one of the union's stated goals has been to eliminate service-time manipulation. That's easier said than done, since almost any free-agency system that isn't based on age can and will be taken advantage of. Still, we feel obligated to point out how this particular proposal may encourage more service-time manipulation.

Stipulating that the bonuses will be paid from a league pool rather than the teams themselves is a nice touch to protect against bad-faith actors, but the incentives are still in place for teams to hold down their prospects. And that's without learning whether or not the bonuses could be used as part of arbitration hearings, which, in turn, would give teams more reason to prevent their top rookies from earning them.

The union undoubtedly recognizes this -- they aren't stupid -- and probably views it was a necessary evil to rward top performers who happen to be in their first or second full seasons. Viewed through that prism, the reward system is more effective. For an idea of who would've (and who wouldn't have) received a bonus last season, take a look at the chart pieced together by Grant Washburn of Pitcher List:

On EW, @megrowler mentioned how some pre-arb players would miss top-30 WAR well within the margin of error. I wanted to see what that would look like for 2021.

— Grant Washburn (@throwing_gasse) January 28, 2022

The list includes a CYA winner, the ace of the best team in the AL, and a #1 prospect held down for service time. pic.twitter.com/DBXD2SHLPI

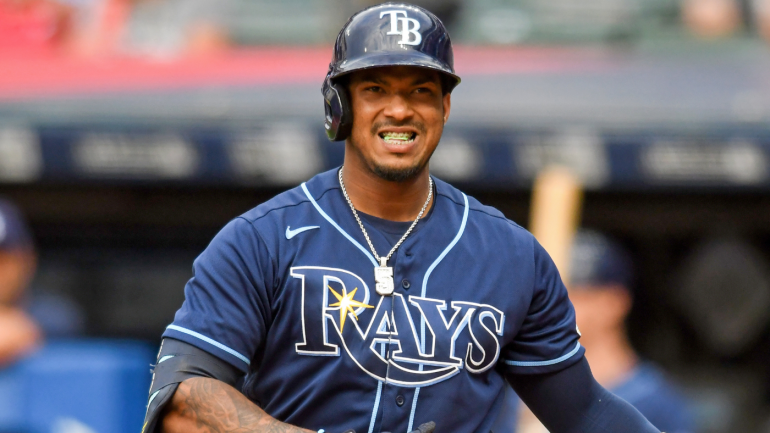

We'll highlight two names on the "just missed" portion of Washburn's list: Wander Franco, who fell short because his team suppressed his service time as described above, and Shane Bieber, who was limited to 16 starts by injury. We've addressed the Franco situation; now, let's turn our focus to Bieber's.

3. Could set undesirable precedent

On the surface, coupling compensation and performance is an intriguing proposition. The best-performing players are the ones producing the most value, so why shouldn't they take home the most reward? Injuries and down seasons happen to everyone, though, and that's why the MLBPA should be wary about inadvertently embracing a pay-for-play model where salaries are dictated by little more than a formula.

The nature of baseball's current contractual system is that both sides assume risk. The players take all of it early in their careers, when poor play or injuries could derail their chances of ever landing a big payday. That risk is supposed to shift toward teams once players are able to hit free agency. In recent years, teams have shied away from taking that risk, turning instead to short-term arrangements for everyone but elite players.

It makes sense that the union would like to tweak the system so as to subvert teams' behaviors. But sometimes the cure is worse than the illness. In this case, the union should be mindful that their honest attempt at bettering the system could leave a nasty aftertaste in future negotiations.