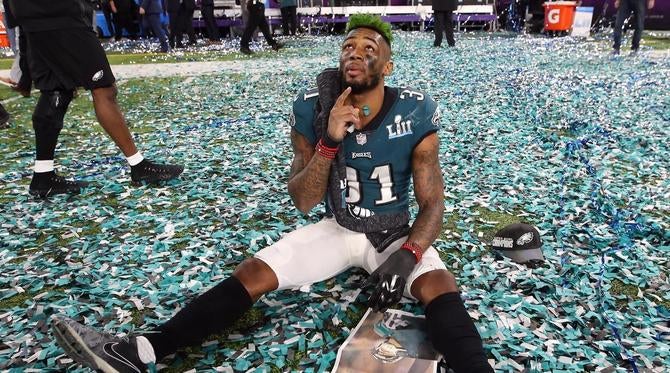

Before Jalen Mills sat euphorically on confetti-coated turf, a "Super Bowl LII" logo stitched to his jersey and Philadelphia's first Lombardi Trophy in the vicinity, he was just another name in a football league full of them.

Before he started for the Eagles as a personal favorite of defensive coordinator Jim Schwartz, he was just another seventh-round draft pick, the 21st-to-last player taken out of 253 in 2016.

And before he starred with another group of Eagles at DeSoto High School in a suburb of Dallas, he was just another boy in a single-parent home, a witness to elementary insults about everything from fashion to upbringing.

Still slender but years away from his chiseled 191-pound NFL frame, the grade-school Mills was born in Dallas and first went to a private school -- "not one of the best," he says over the phone from Philly.

The main culprit: bullying.

"It was everywhere," he says. "My school, we had to wear uniforms. There was a certain color you had to wear each week, and that was typically because a lot of kids didn't have a lot of their own clothes. It kind of got you away from kids talking about you, but then some kids would still only have two pairs of shoes. Others would have six or seven pairs of shoes and treat you different."

The hardships weren't unusual (70 percent of kids have seen bullying in school, per the U.S. government), but for Mills, they went beyond his wardrobe. Money was a luxury. And he was frequently the new kid, moving around Dallas from one apartment and house to the next.

The problem now, of course, isn't whether Mills has enough shoes to wear or enough friends by his side. It's choosing which pair of shoes he's going to wear and which fellow multi-millionaire he's going to call.

At 24, he oozes high-class superiority. On the field, there's not a cornerback more sure of himself outside of maybe the Jacksonville Jaguars' Jalen Ramsey. Any chance he's even remotely involved in a tackle or pass breakup, he wags his finger or flexes his muscles with his arms by his side. Off the field, he pairs his green-dyed hair with custom earrings, designer bags and the occasional shirtless suit.

Who's bullying that?

And yet the riches that may have washed away childhood worries are not what have Mills unusually content this early week of October. Smack dab in the middle of a slow start by his defending-champion Eagles and a torrent of criticism over his own play, this young man is especially at peace not because of his outfits or shoes or even his team's still-fresh Super Bowl win, but rather because of one other very specific thing:

A children's picture book.

Three weeks after playing in Eagles quarterback Carson Wentz's inaugural charity softball game in June, Mills hosted his own event in partnership with baseball's Reading Fightin Phils. The game's proceeds happened to benefit the National Youth Foundation (NYF), a nonprofit striving to promote equality among children, particularly through literary programs that challenge and equip students to create art with anti-bullying themes. It didn't take long before Mills sought to lend his own hands to the kids involved.

"He wanted to do more," says Sophia Hanson, NYF's co-founder.

So over the next several weeks, as part of the foundation's Youth Writing Workshop, Mills helped create a 2018 Anti-Bullying Poster Contest, then shared his story with eight different girls from three different elementary and middle schools in the Centerville (Delaware) and Kennett Square (Pennsylvania) area. Those girls -- Alex, Ginger, Isabella, Janet, Julissa, Maile, Mallorie and Victoria -- went on to write, edit and illustrate Mills' journey.

"The competition for which art pieces would be included was very fierce," Hanson says. "I think the art was the most fun for them because of the green hair. They tested lots of greens until they found the perfect 'Green Goblin' color."

The final result, complete with the contest-winning poster drawn by 9-year-old Isaiah San Juan: Mills' own 24-page hardcover biography -- assembled by kids, for kids and in the name of no more bullying.

@NYFUSA is pleased to announce that the @greengoblin hardcover books are in!!! The @Eagles @SuperBowl Champion will be in #Philly to read to kids. #Literacy #Diversity pic.twitter.com/iLXI0wI3Uy

— NYFUSA (@NYFUSA) September 29, 2018

"Man, it's crazy," he says. "You look at the cover, and it's crazy that I'm on a book. When I first seen it, I was like, 'That's lit.'"

Even crazier: The book showcases Mills as an inspiration for kids like his younger self.

If he's being honest, some of his trademark confidence as a cornerback stems from the fact he simply had no choice but to weather his upbringing. ("You get bashed as a kid, but there's nothing you can really do about it," he says. "The household I stayed in was the household I stayed in.") Like Jalen Ramsey, he still talks lots of trash when he's on the field, too. ("Yeah, I'm definitely not allowed to share my go-to line," he laughs.) Even his hair color probably comes from brashness he inherited early on. ("I'm green forever," he promises.)

That bully-bred confidence might also be why he's so straightforward, if not bullish, about his Eagles, who he "100 percent" thinks will be among the NFL's top defenses by season's end.

"I think our confidence is high regardless of our record right now," he says. "Being 2-2, I think it kind of stirs things up on the team, and when I say stirs things up, I mean in a good way. It gets guys hungry. Some guys are angry. We've got guys who block out everything and go into complete focus. Our confidence is super, super high, and we're ready for this Sunday."

More than anything, though, Mills' roots are what make his voice and his platform meaningful.

One of the final pages of his children's biography reads: "Jalen decided to use his fame to help kids take a stand against bullying." Jalen decided to use his fame to help. Few words have brought this third-year veteran greater peace -- 2-2 record or Super Bowl title or not.

"To be able to turn nothing into something and have the ability to give back is a dream come true for him," says JaCary McClinton, Mills' brother and personal manager. "It's amazing to see children look up to him because we didn't have any specific role models growing up."

The credit for Mills' story goes all over. It "starts with God," the cornerback says, but the list goes on: His mother, Kisa; the teams that adopted him; teammates like Chris Long and Malcolm Jenkins, whose community efforts motivated him; and NYF, which Hanson says aspires to donate copies of Mills' book to "every public elementary school in Philadelphia."

And it all began well before Jalen Mills sat on confetti-coated turf, just another man with a difference still to make.