The phone buzzed on Will Wade's pillow at 12:57 a.m.

Wade, LSU's men's basketball coach, rests his cell phone next to his head on Thursday, Friday and Saturday nights during the school year. Ask many a college coach, and they'll tell you the calls you don't want almost always come after midnight.

That night, Wade cracked his eyes and saw that one of his players, freshman Javonte Smart, was ringing him. He picked up expecting to hear Javonte's voice. Instead, it was another one of his freshmen, Emmitt Williams, who was overwrought. He and Smart had been eating at Waffle House when they saw police cars speeding by with their sirens on. Smart and Williams were making their way back toward where they were earlier that night with teammate Wayde Sims. Moments after seeing the police cars, Williams received a call from a friend who told them Sims had been shot.

A gut-churning video of the incident was circulating on social media. It was because of this that a friend called Sims' mother, Fay Sims, and woke her up.

"She was frantic and certain it was Wayde," Fay said.

Williams and Smart got in the car and raced to the scene at 600 Harding Boulevard on the north end of Baton Rouge, Louisiana, near Southern University's Mumford Stadium. Minutes later, Williams had Smart's phone and called their coach. He repeated the same two words.

"He's dead. He's dead. He's dead."

"As a coach, you think he's overreacting," Wade said. "He was shot, but I didn't want to obviously believe he was dead."

Williams and Smart followed the ambulance speeding their teammate to the hospital. Wade made his way posthaste. Fay and Wayne Sims beat their son to Our Lady of the Lake Hospital by about 5 minutes. Initially, they did not know whether Wayde was alive or dead, but approximately 20 minutes after Wayde was brought in, a doctor came out to deliver the news.

Less than an hour into Sept. 28, 2018, Wayde Sims, 20, died of a gunshot wound to the head and neck.

Fay and Wayne never got to see their only child that night. His body was a crime scene; law enforcement, guarding the door to where doctors were trying to save Wayde, would not let his parents through.

"It was hurtful for us because we couldn't go see him, touch him," Fay said.

They wouldn't see their boy again until more than week later when his body was embalmed in an open casket at his funeral.

By the time Wade got to the hospital, Williams, Smart and former LSU teammate Brandon Sampson were waiting in the emergency room alongside Wayde's parents.

"I pretty much knew when I walked in that he was dead," Wade said. "His dad came up and confirmed that to me. ... You watch one of your players go to the coroner in a body bag, going into the van, we knew that was him. You almost fall to your knees."

The killing of Wayde Sims was a senseless act of violence that culminated after an altercation that still has no clear impetus or reason. Sims, Smart and Williams, along with some other friends, attended a concert at Southern University earlier that night, then stopped by a fraternity party before making their way back to LSU, which is approximately a 10-minute drive. Sims stayed back with a friend.

What happened after that remains, largely, a frustrating mystery. It's believed Wayde stepped in to stop his friend from being pummeled. From there, a suspect identified as Dyteon Simpson, pulled out a gun, pointed it at Sims and killed him, police said. Simpson, who police say has confessed to the shooting, is facing a second-degree murder charge with the potential for a life sentence.

"Javonte and Emmitt saw him before they left," teammate Skylar Mays said. "Wayde checked to see if they were OK to drive and had everything in order to leave."

Mays, Sims' oldest friend, awoke the night of Sims' death to an eruption of texts, all of them in some variation of I'm sorry or Stay strong, Sky.

"You don't even know what they're talking about," Mays said. "You don't know what to think, and then to get that call that your best friend was shot. … Can't explain it. You can't explain that type of sorrow."

Skylar and Wayde were supposed to spend their college careers as best friends on and off the basketball court as they brought LSU back to national prominence. One dumb impulse from a stranger obliterated that. Skylar was called upon to be one of Wayde's pallbearers. He carried his best friend to the grave.

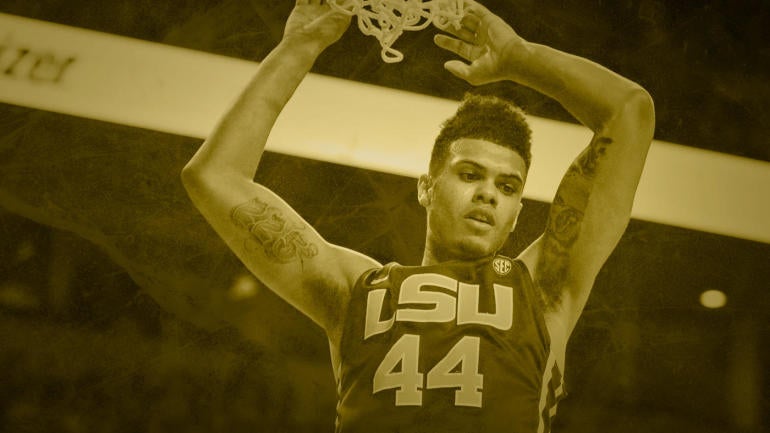

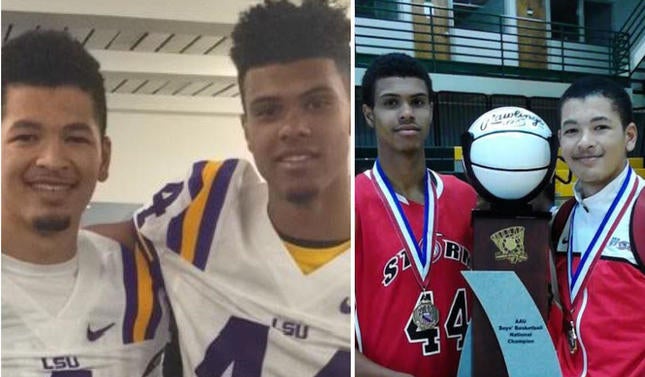

Wayde Sims was made for LSU. He grew up 10 minutes from campus and was as perfect a fit for the Tigers as you could find. He attended University High, which is on LSU's grounds. Wayde's father played for legendary Tigers coach Dale Brown in the late 1980s and early 1990s. While at U High, Wayde and Skylar won state championships. Wayde totaled 3,045 points and 1,613 rebounds on his way to being named the best high school player in the state of Louisiana.

After former LSU coach Johnny Jones, Wayne Sims' cousin, was fired following Sims' freshman season, Will Wade got the job. Wade said Sims was one of the first to completely embrace the new staff.

"The two best words you can describe anybody are 'dependable' and 'consistent,'" Wade said. "He never missed a practice, never missed a day."

The bitterness over Wayde's death was all the more infuriating and heartbreaking because those around him said he took a huge step as a person and as a player in the offseason. He was expected to be an important piece for this team in 2018-19. A common refrain in recent months for 21-4 LSU has been: Think how much better we'd be if Wayde was here.

"He had big things coming for him this season before everything happened," Wayne Sims said. "We had high expectations. All that comes to a screeching halt."

LSU's first official practice was scheduled for the 6 a.m. hour that Friday of his death. Instead, the team wouldn't fully practice until 10 days later -- after Wayde was buried. Wade is not a helicopter coach. He doesn't demand curfews. Rather, he tries to curb against players staying out late by holding practice so early.

"We pretty much always do something on a Friday morning. It's just to make sure Thursday night goes smoothly," Wade said. "You look back at everything that's gone on and you look back at anything you could have done, you go through the blame game. Bob's helped me with that. You go back through every scenario."

Wade is referring to Bob Delaney, a former director of NBA officials who was coincidentally hired to be an officiating adviser to the SEC weeks before Wayde Sims was killed. SEC commissioner Greg Sankey brought Delaney on for his rules oversight, but Delaney is also a former law enforcement agent who successfully infiltrated the mob only to deal with severe anxiety, depression and traumatic stress as a result. He's counseled the U.S. military, 9/11 first responders and dozens of everyday Americans affected by mass-shooting incidents in recent years.

Delaney and other counselors proved vital in the coping process not just in the days following Sims' death but the months that crept along without him.

"How are we going to be intentional in understanding each person's grieving process as well as their interaction with trauma?" Delaney said. "When you experience a traumatic event, it peels the wound back on other traumatic events. It's like a scab that went over a wound gets knocked off. Will and his staff and his players, as well as the community and the university, were going to be dealing with a tremendous amount of emotion."

Players were encouraged to be as open and emotional with Delaney, a neutral supporter, as they felt comfortable. But Mays is still caught in a loop where he's trying to stay positive while knowing a part of him is never coming back.

"I don't think it's ever going to feel normal for me as long as I'm playing ball here," he said. "We expected Wayde to have a great year for us and be one of our team leaders because he had that type of summer. We expected him to make a big jump. The biggest asset he was going to bring to our team was his energy, that caring personality and a guy that keeps guys together, keeps guys with the right mindset. He would've done that just being who he was. … There's just some people in this world that everyone gravitates toward you."

Mays, a junior shooting guard who has started every game this season, is averaging a career-high 13.0 points. Everyone in that program feels the void without Wayde, but Skylar's plight is especially acute.

"Skylar is deeply hurting," Fay Sims said. "He made a comment that it feels like Wayde's on his vacation without his phone."

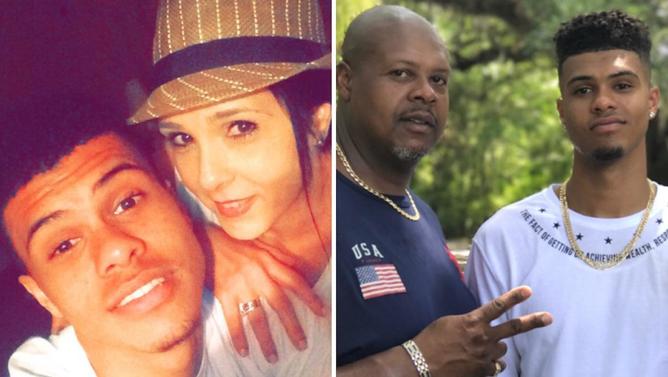

Those who knew Wayde best describe him not just as a momma's boy, but as a grandma's boy, too.

"He was really caring for everybody," Fay said. "He didn't see the wrong in people."

He was also a city-dwelling outdoorsman. Wayde loved fishing, going so far as to get a boating license. He'd go bass fishing at Lake Fields, southwest of New Orleans. Sometimes he'd sneak a quick hour at the pond behind his parents' house, squeezing in the time before midday practice. He'd hop in the trawl-motor two-person boat, even convincing nervous teammate Brandon Sampson to come along. (Because of Wayde, Sampson eventually grew to enjoy fishing, which he now does on occasion.)

Father and son began to take on big adventures, like saltwater angling and going hunting for red fish and trout in the summer of 2017. They'd head out before sunrise and creep down the marshlands well south of New Orleans, combing through brackish water until the sun's blaze baked them nice by noon. On their first trip, Wayde caught a 3-foot red fish. It took him more than 20 minutes to reel it in, tiring him out.

Then he caught another one.

Wayne still makes time to do the big fishing trips once in a while. As he waits and watches on the boat, his mind will drift. He thinks about his only child. He thinks about the trips that will never be.

"For me, after everything happened, I've questioned God," Wayne said. "Why was he taken away from us? I understand it was a devilish act that happened. What is the purpose? Is there something good that's going to come out of this? Now that we don't have our only son, we miss him dearly and each and every day is a struggle."

The Sims have gone to every court proceeding and will continue to do so until if/when Simpson is convicted. The case has hit stalls -- Wayne personally knew the former judge in the case, causing a conflict of interest and prompting a new judge to be assigned -- but they are hoping to have a resolution this year.

"It's important that Wayne and I are there," Fay Sims said. "I guess we're Wayde's voice now."

Added Wayne: "Our son was taken away from us, so if it takes for his life, not in the physical sense, but if it takes a life sentence, that's what I want. No plea bargains; we want justice to be served."

Things have not been easier in the five months that have passed, in part, because the Sims don't have reasons for why their son was pointlessly killed. Closure is that much harder to encircle. They also know the horrific video captured on social media is there for them to watch if they choose, but they refuse. Fay said she knows some who watched it and vomited as a result.

"We don't have a whole lot of facts," she said. "A fight broke out, Wayde stepped in, and the guy had a gun and shot him and killed him."

Every few weeks brings a new threshold to cross, all of them painstaking. After the initial whirlwind of grief, the funeral, the onslaught of beloved company ... then came the optimistic-yet-dreaded opening of LSU's season six weeks later.

"It literally takes my breath when I walk into the PMAC," Fay said. "[Some days are] just way too emotional. When I first walk in, it cuts my breath."

Thanksgiving for the Sims meant an open seat at the table. On Dec. 13, 2018, what would have been Wayde's 21st birthday, nearly 40 people went to his gravesite in the rain and for a ceremonial balloon release.

"I don't even remember December too much," Fay said.

Christmas brought no seasonal decorations last year; Fay took a few Christmas items and adorned Wayde's gravesite -- still waiting to have its tombstone embedded -- with holiday bibelots. Then came the unexpected emotional gush of Dec. 31.

"For me, personally, it was New Year's Eve that was the worst," she said. "That was having to leave 2018, although I kind of felt like I hated of 2018 for taking our son, and didn't want to see 2019 come in because Wayde wasn't a part of it. It's gut-wrenching; it's excruciating pain. I miss him dearly."

Friends have remained supportive. The Sims' nest has not had the opportunity to become empty. But as the season goes along and LSU keeps playing better, things seem to grow that much more difficult.

LSU has gone through an extraordinary -- and partly controversial -- run this season. Weeks after Wayde's death, Wade and his program came under scrutiny and skepticism after information via wiretap was brought up in federal court (lacking complete context) that illustrated Wade on the phone in 2017 with the now-convicted Christian Dawkins in discussions over a blue-chip recruit.

Wade was asked about both that revelation and going through dual-yet-separate personal tribulations.

"It puts everything in proper perspective for you," he said. "It shows you what's really important and rattles you."

When asked a follow-up question about the wiretap, Wade declined further comment.

The death of a player and the exposure of potential/alleged NCAA rule violations are matters detached in importance. But they've also been heavy, obvious, unavoidable storylines -- both of which came to light in the preseason -- as the Tigers have put together one of the more unexpected success stories on the court in 2019.

Watch LSU and you'll see teammates affixed and fond of one another. The body language is affirming and positive. The Tigers are talented, of course, but they're also driven and focused.

"You could see a bonding that takes place where they're taking care of each other in small ways that may not be Earth-shattering, but a guy grabbing another guy by the back of the neck and kind of holding on to him," Delaney said. "This is not just emotional and psychological. There's a physiology to this. It's amazing how, when we we go through trauma, people are resilient. We're more resilient than not. When that kind of love comes together, people can do extraordinary things."

LSU opened its season in nondescript fashion with a 7-3 start. Since then, the Tigers have gone 14-1, climbed to their highest ranking in the AP Top 25 in a decade (No. 13) and improved to 21-4 overall, tied atop the SEC standings with Tennessee.

There have been unlikely endings, like the basket interference that wasn't called and thus sealed a win against No. 5 Kentucky on Feb. 12. That gave LSU just its second road win in 37 games all time against a top-five opponent. There was the unreal rally Jan. 26 at Missouri -- down 14 with 2:10 left, the Tigers' chances of a win at 0.2 percent -- that ended with an 86-80 LSU victory.

"We're going to have six and the other team's going to have five," Wade said. "I think that's the best way to explain what happened at Missouri. It's something that's with our team. Any time you go through something like that as a group, it's tough. You never know how you're going to react."

LSU has also won in overtime against Arkansas and Mississippi State, the latter featuring an unlikely bounced-in 3-pointer by Javonte Smart to help seal it. A similarly improbable 3-point shot was made by freshman Naz Reid in the Tigers' 83-78 win against Auburn on Feb. 9.

"We like to say that Wayde's made great friends with God," Mays said. "Some of the shots we make, like when Javonte hit the 3 and popped it up and in -- similar to how Naz made his 3 at Mississippi State -- we like to say Wayde tapped that in a little bit."

The team has honored Wayde in a number of ways. His No. 44 -- the same number his dad wore at LSU -- is stitched to the uniforms. Some players have taken to writing his name and number on their shoes. All Tigers now finish their weightlifting sessions with 44 reps of bicep and tricep curls. At home games, the team taps his locker before it leaves for the court.

"We're definitely playing for something bigger than ourselves," Mays said. "Amongst all the tragedy and what happened in the past, I feel like we're finding a way to use what happened to give us an extra edge and a drive."

Wayde's locker has gone untouched since he died. His playbook is tucked behind his shoes. His practice gear and uniform dangles from the hooks. Wade sits alone in front of the locker once a week, early in the morning, to reflect.

"You look at his locker, and you're in the film room, you almost think he's been gone a few days and he'll be back," the coach said.

Delaney and others helped LSU organize and keep structure as the season started. Everything physical in regard to handling Wayde's loss had to be intentional. His uniform was draped over a seat in the front row of the middle of the team picture. The locker was kept as it was as means of not leaving an empty space for the players to be around the entire season.

"They lose him once, they're losing him again if you do that," Delaney said. "The team atmosphere really helps protect them."

LSU travels with a counselor for its road games and has support staff available for the players and coaches when on campus. Small things can prompt memories of Wayde -- good or bad -- the emotions of those triggers offering up unpredictable reactions. Routines from previous seasons -- Who were the teammates Wayde would sit next to on plane and bus rides? Who would he room with on the road? What songs did he like to play before a game? -- are paid more careful attention.

"There's a lot of things that I've learned through all this," Wade said.

This is Wayde Sims’ locker. It’s remained as he left it since last September. pic.twitter.com/sCzK7K8Lrw

— Matt Norlander (@MattNorlander) February 20, 2019

Wade has spoken with veteran college basketball coach Oliver Purnell, who lost a player in his sleep when he was at Dayton, and consulted with former Vanderbilt football coach Bobby Johnson, who had a standout player murdered during Christmas break in 2004.

"Sometimes when there's a suddenness to things that triggers you back to being in the hospital," Wade said. "There's a lot of things that can pop up and jolt you and jolt different members of your team at different times."

For example, it's customary for teams to watch tape of conference opponents and use video from the prior season as means to scout and prep. But for LSU, that film has Wayde on it. Wade will not let his players watch that. He has eliminated it from team prep -- though he and his coaches have watched it, and even then, it's as comforting as it can be spooky. He's on the screen but not in the room.

"The jolt is how you forget that you forget the film from last year, it's Wayde making a play," Wade said. "He pops up. We don't want to necessarily trigger that if we don't have to. But as a coaching staff and me, personally, when I watch it, it's very jarring still to this day."

Cruelly, Wayde's slaying wasn't the first brush with death via gun violence with which the team has dealt. LSU's quietly gone through other trauma with players' family members. Prior to Wayde's death, the team had been involved with the TRUCE program, which targets at-risk areas -- like near where he was killed -- in Baton Rouge.

For LSU, Wayde Sims is now a face of the issue.

"That's what we've tried to transition to, to turn our anger," Wade said.

LSU's most important moments this season have been equaled or surpassed in private or away from the limelight just as much as the huge victories. Four days after the slaying, Skylar spoke at Wayde's candlelight vigil in front of the Pete Maravich Assembly Center. A few days after that, he got to see his friend one last time.

He remembers it with a pause in his voice.

"Walking up to the casket, your knees are weak because you're not ready, but you want to see him," Mays said. "I was honored to be a pallbearer, obviously. I thank Ms. Fay for allowing me to be a pallbearer. That meant the world to me. They had an unbelievable amount of people there and it shows how many people cared about Wayde."

Skylar and other former teammates of Wayde have taken trips his grave with his mother. She's become a rock for Wayde's friends, to allow them to be vulnerable and cry when needed. She tags messages with plaintive expression: #forever44💔

"Fay and I are doing the best that we can to live without him, because it's a big hole when you lose a kid like that," Wayne Sims said. "A big void."

They take two or three trips per week to the cemetery now. It's their only way to feel some modicum of comfort. On the court, Wayde will be honored in a big way come March: At the SEC Tournament, the conference plans to name him this season's SEC Legend for LSU.

"He's always around, he's always in our minds," Wade said.

But he should be there. This season is not a dream one. It's real, it's painful, it's beyond bittersweet. There is no redemption possible here. The Tigers' success in absence of their murdered brother is a racking reminder, on a daily basis, how unfair life can be. The emotions and subtle aftershocks of his death are still coming out for many who knew him and probably will long after the final game of this season has been played.

This team is forever together but forever broken.