OAKLAND, Calif. -- When Steve Kerr decided it was time to rest four players in mid-March, his team had already won 51 games and was cruising to the best record in the Western Conference by a landslide.

Still, the complaints rolled in – angry emails and tweets directed at Kerr from fans who’d paid good money to see the NBA’s best team and its All-Star backcourt of Stephen Curry and Klay Thompson.

“It was somewhat controversial,” Kerr deadpanned last week while preparing his team for a trip to the NBA Finals.

Just a sample of the Twitter backlash directed at Kerr: “Nothing like spending $250 on tickets for my son’s 7th birthday only for you to bench his favorite player. Thanks Steve.”

Ouch. And that wasn’t all. Thompson’s family had bought a huge block of tickets for the game in Denver on March 13, only to see him benched along with Curry, Andrew Bogut and Andre Iguodala. The Warriors lost 114-103, but won in the long run.

Here’s how.

Kerr didn’t draw names from a hat or use a coach’s intuition in deciding his key players needed a break. He used information gathered from wearable technology, the next frontier in the NBA’s rapidly accelerating analytics movement.

On the heels of a six-game, nine-day road trip, players were reporting that they were starting to feel worn down. Golden State’s director of athletic performance, Keke Lyles, has players fill out a questionnaire every morning to measure soreness, fatigue, sleep quality and other factors that are so important to recovery and injury prevention.

In addition to the red flags on the players’ questionnaires, the data Lyles had been collecting all season – using the NBA’s SportVu cameras in games and wearable technology from Catapult Sports in practice – confirmed his fears.

“We felt like all those guys were reaching their limits,” Lyles said.

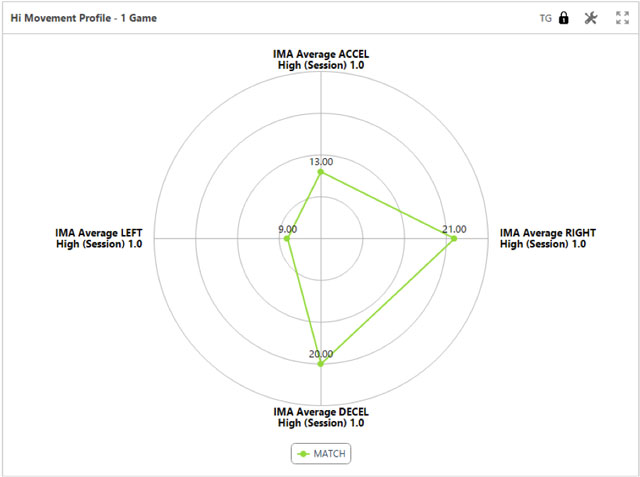

With player movement captured at 25 frames per second during games with SportVu cameras, teams can monitor players’ movement intensity and acceleration – and spot drop-offs that might indicate fatigue and overuse. Layering that in-game data with metrics from a biomechanical movement device that the players wear in practice, Lyles reported to Kerr that it was time to take action.

“A lot of non-contact injuries are fatigue-related,” Lyles said. “If we see big drops consistently over the last few games, and we know in practice they’ve dropped and they’re telling us they’re tired and sore and beat up, then we start painting a big picture: ‘Yeah, these guys are probably fatigued.’ When they’re fatigued, they’re at a higher risk.”

Kerr, ringleader of the most entertaining basketball show on Earth this season, didn’t take the decision lightly. He even emailed fans to explain the reasons behind his decision.

“We don’t like the idea of sitting someone out because fans pay,” assistant general manager Kirk Lacob said. “We get it. But we did agree that if we got to this point, we would sit them out.”

“This point” was a place where the Warriors – especially stars Curry and Thompson – arrived after the All-Star break. Lyles and the training staff had developed pre-set parameters for what they considered to be a danger zone; a combination of the player feeling fatigued and proof of diminished load capacity in the SportVu and Catapult data.

“We found that we had multiple guys red-lining,” Lacob said. “It was an easy decision. … Steve actually said, if one of those guys got hurt and he hadn’t sat them out knowing that information, he could never forgive himself.”

Catapult is an Australian company on the cutting edge of biomechanical analysis – the ability to monitor how an athlete is moving. This season, 12 NBA teams including the Warriors used its monitoring device, which is about the size of a car clicker and fits into the lining of a compression shirt.

The tiny device features a location-positioning system (indoor GPS); an accelerometer to measure stops and starts; a gyroscope to measure the body’s bending and twisting; and a magnetometer to measure direction. Oh, it also has a microprocessor that collects and parses more than 1,000 data points per second, beaming them to the trainer’s screen of choice in real time.

At least half the NBA teams using the device also have their players wear heart-rate monitors at the same time to track what’s going on inside their bodies in response to training. The coaching staff can monitor every player’s movement patterns and physiological responses in real time, and all the data can be integrated to provide a complete picture of how a player is moving and how his body is responding to it.

George Orwell, please pick up the white courtesy phone …

“It’s gotten to a funny point where we have to ask the first question: What data can we understand and how is that going to be helpful?” Lacob said. “And the secondary questions are, what are we allowed to do? What is philosophically OK to know? How much should you know about your employees? How much should you allow your employer to know about you? And those questions are going to get raised in the CBA.”

At the NBA level, wearable technology can only be used in practice for now. In-game use must be collectively bargained with the National Basketball Players’ Association, and executive director Michele Roberts can see the value.

“To the extent that the team and the player could come up with a better advantage based on the information, who’s got a problem with that?” she told CBSSports.com.

But with progress comes problems. Who has access to the data? Are there limits to how it can be used? Roberts said at least two agents have alerted her to teams citing wearable data during contract negotiations.

“Opinions are being formed about a player’s potential based on how some people are reading, reviewing and assessing the data,” Roberts said.

As with rule changes like the international goaltending rule and instant-replay, non-unionized players in the NBA Development League have served as guinea pigs in the sport’s experimentation with wearable technology. Several D-League teams have had players wear various forms of it during games, including Catapult and its competitors.

Maryland-based Zephyr Technology Corp. makes a bio-harness that allows coaches to see markers of training intensity like heart rate, breathing rate, core temperature, acceleration and more – beaming the data to laptops, tablets or phones in real time. Illinois-based Zebra Technologies International makes trauma-monitoring stickers that are affixed to the player’s body to measure force and impact – an important innovation as the NBA and NFL try to gain a better understanding of concussion risk.

At the draft combine in Chicago, Santa Barbara-based P3 was hired by NBA teams to use motion-sensor technology to analyze movement patterns of NBA prospects – providing a window into dysfunction or imbalances that might be precursors to injury.

The Mavericks, Warriors, Rockets, Grizzlies, Knicks, Magic, Sixers, Kings, Spurs and Raptors are among the NBA teams that used Catapult this season. Zephyr lists the Pacers, Timberwolves, Thunder and Suns among its NBA clients. The Cavaliers, Golden State’s opponent in the NBA Finals, also use Zephyr to monitor their players.

The Rockets, always at the forefront of technology, use both, GM Daryl Morey said.

“I think we’re on the verge of a little bit of an explosion in terms of understanding the human body using technology,” Lacob said. “It’s going to be like a title wave of information.”

Next season, Catapult anticipates having 16-20 NBA teams using its devices in practice. And compared to the money teams are investing in players, the cost is minimal; a full complement of 15 devices costs approximately $30,000 for the season, said Brian Kopp, Catapult’s president of North American operations. For the Warriors’ $72.6 million payroll this season, that amounted to .04 percent of the team’s salary expenditure. More money, one would imagine, is spent on room service during any given road trip.

Does it work? That’s hard to quantify. The NBA tracks data on games lost due to injury, but does not make it publicly available. Defending MVP Kevin Durant played only 27 games this past season due to foot injuries, and so many stars were sidelined during the playoffs -- Chris Paul, John Wall, Chandler Parsons, Pau Gasol, Kyrie Irving and Kevin Love, among others. Depending on your perspective, it could mean the technology isn’t doing any good or is more necessary than ever.

“It’s hard for freak accidents, but I’m sure it could help some guys,” said Shaun Livingston, who has his doubts about whether any amount of technology could’ve prevented the catastrophic knee injury he famously suffered in 2007. “All the information that you could possibly get, we would use it, especially at this level. It can only help you.”

Commissioner Adam Silver has vowed to limit back-to-backs and four games in five nights in order to save wear and tear on the players’ bodies, and the NBA is examining a variety of measures to improve players’ health -- from planes with fully reclining seats to the longer All-Star break that was implemented this season. But to date, the league and union have engaged in no substantive discussions on an issue that will be prominent in the next round of collective bargaining.

“Wearable technology is an important part of the player health conversation,” said Mike Bass, the NBA’s executive vice president of communications. “We’ll work with the players’ association to establish the appropriate operational and data privacy rules.”

As was the case early in the NBA’s robust advanced metrics movement, the technology and information are ahead of the human ability to interpret and use it. No science is perfect, and trainers and coaches understand they will never achieve a failsafe method of predicting injuries. But some of the early returns, however anecdotal, are encouraging.

Two seasons ago, the Raptors were among the most injured teams in the NBA in terms of games lost; after adopting the Catapult technology, they were among the NBA’s least-injured teams in 2013-14. Of the eight Warriors players who logged the most minutes this season, only one – Bogut – missed more than six games. (One of those players, Marreese Speights, has been out since May 9 with a calf strain.)

“We’re never going to get to 100 percent, but it’s about making more intelligent decisions,” said Kopp, who became well-versed in the NBA’s eager analytics culture as a former executive at STATS LLC.

“There’s a reason Steph and Klay and Draymond [Green] only played 32 minutes a night; we could’ve played them more,” Kerr said. “The reason was, we wanted to rest them and we were doing really well so we could afford to rest them. … I’m not sure Steph was thrilled about sitting out 18 fourth quarters, but he understood. He’s still standing and playing his best basketball of the year.”

For Kerr, the a-ha moment actually came after that Denver game in which is rested four players. Three days later against the Lakers, Thompson sprained his ankle and missed three games.

“It’s not a perfect process, but these guys were teetering on the edge of being overused and one of them sprained his ankle on a typical play,” Lacob said. “That, to us, said enough.”

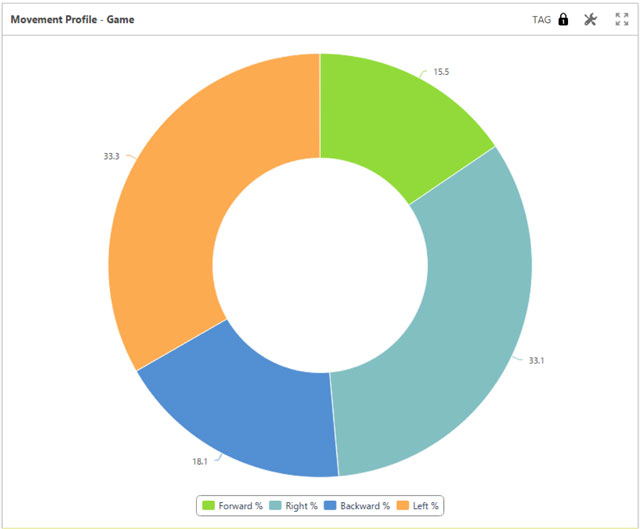

Some teams have used the directional data generated by the devices to change their training methods to better suit what players experience on the floor. For example, Raptors director of sports science Alex McKechnie noticed that 80 percent of the players’ movement in practice was side-to-side and backwards. So what was the point of having the players move forward in a straight line most of the time during conditioning drills?

“He started to change how he conditioned the players,” Kopp said.

McKechnie’s observation was backed up by Catapult’s work with a D-League team last season, yielding in-game data showing that only 15.5 percent of player movement was forward.

The device can also detect whether a player is leaning a certain way when he cuts, jumps or lands, or whether he’s favoring one side vs. the other – possible early indicators of injury, muscular imbalance or movement dysfunction that can be addressed proactively with training and therapy.

“We’re trying to do this to extend your career and maximize your performance,” Kopp said. “That’s something all coaches like.”

Well, not all coaches. At a presentation on wearable technology organized by coaching agent Warren Legarie last year in Chicago, Bulls coach Tom Thibodeau raised his hand. Everyone in the audience knew where this was going.

Thibodeau, fired last week by the Bulls and replaced by Iowa State’s Fred Hoiberg, had resisted overtures from Bulls management to employ wearable technology to monitor players’ recovery, league sources said.

“He was basically challenging it, like, ‘Michael Jordan didn’t need that,’” Kopp said. “Fair point, but one of the most amazing athletes in the entire world, I would argue, would’ve benefited, too. There’s a reason why they call it old school, because it’s been replaced by new thinking.”

But after years of being taught to “listen to their bodies,” players now find themselves in a situation where their employers are doing it for them. And while most have been receptive to the technology, there are legitimate concerns.

“I just get a little worried about information overload at certain points,” Curry said. “It’s kind of the same thing with advanced stats and the cameras in the ceiling and all that stuff. There’s some benefit to it, I guess, from my standpoint. But I haven’t figured out what readouts I really need to pay attention to vs. other ones. It’s kind of an ongoing development.”

The slippery slope begins with playing time being limited, even if it’s for the player’s own good.

“It’s helpful as long as that doesn’t trump my own perception,” Curry said. “Let’s just say it rolls over into affecting games and coaches changing rotations, that’s where you might lose some players. You’re playing five or 10 less minutes less than you think you should because the readout says you’re overloaded?”

For these reasons and more, Roberts said she is “aggressively trying to reach out to the teams and ask them to share exactly what they’re doing in this space” -- even before the next round of bargaining, which could begin as early as 2017. For example, are players signing waivers describing who has access to their data and how it can and can’t be used?

“We need to make sure that the teams appreciate what will be permitted and won’t be permitted and have those discussions and create those best practices through collective bargaining,” Roberts said.

Said Lacob, the son of Warriors majority owner Joe Lacob: “From my perspective, we pay them a lot of money, so we should be able to know what we don’t know. That can be bargained. It can be and it will be.”

Additional data from games would be invaluable to teams, coaches and training staffs. As NBA teams grind through an 82-game regular season, practices become few and far between – resulting in incomplete data and more guesswork than trainers and coaches would like. As the technology evolves, the next frontier is in-game decisions being dictated, in part, by real-time data generated by wearable devices during games.

Far-fetched? Not so much. Australian Rules Football teams are wearing Catapult devices during games, and coaches are making substitution decisions based on the readouts. With NBA players wearing limited protective gear, the devices would have to become smaller to make in-game use practical.

“I don’t like that,” Curry said. “I’d have to become more familiar with that first.”

Coaches may not like it, either. What if the Cavs had data showing that LeBron James was red-lining in the fourth quarter of Game 7 in the Finals, putting him at higher risk for injury? Does anyone really think David Blatt would sub him out – or that LeBron would allow him to? Would anyone in Cleveland accept benching LeBron as opposed to giving him a chance to chase down the city’s first pro sports championship in 51 years?

“We had a soccer client and the trainer actually went to the coach and said, ‘This guy has an 85 percent chance of getting injured,’” Kopp said. “And basically, the coach looked at him and said, ‘I need him to play,’ and the guy went out and pulled his hamstring that game.”

So imagine a coach on the bench with an iPad telling Gregg Popovich when it’s time to send Tony Parker or Tim Duncan to the bench.

“Pop doesn’t need computers,” Kerr said. “He has his own brain and it gathers all this data and he figures it out on his own.”

Oh, to the contrary. The Spurs and Mavericks were Catapult’s very first NBA clients, adopting the technology after the 2011 lockout. But even Popovich, a former spy, should appreciate the Orwellian question of how closely “big brother” should be watching.

“What I tell players all the time is, this is for you,” Lyles said. “This is your career; this is your paycheck. We’re trying to help you. Ultimately, we benefit from you being healthy.”

And so do the players.

“Really,” Lyles said, “it’s a win-win.”

But not a perfect science.

![[object Object] Logo](https://sportshub.cbsistatic.com/i/2020/04/22/e9ceb731-8b3f-4c60-98fe-090ab66a2997/screen-shot-2020-04-22-at-11-04-56-am.png)