Here's the reality about NCAA investigations and penalties: Every school wants this thankless job to happen -- until the finger gets pointed at them. Big Ten commissioner Jim Delany, a former NCAA investigator who admits he doesn't thank NCAA enforcement enough, recently hoped to produce "game-changing" ideas to improve the system.

Delany chaired a subcommittee on NCAA enforcement for the Collegiate Commissioners Association (CCA), a group of all 32 Division I conference commissioners. Over the 18-month review, the commissioners discussed several outside-the-box ideas.

One idea was to seek governmental subpoena power for the NCAA to compel witnesses to cooperate. Another was to create separate jurisdiction to divide real serious cases from narrower cases. Delany especially liked the idea of outsourcing NCAA investigations and penalty decisions to an independent third party. None of the proposals got much support.

"To be honest with you, you could read into the 32-conference report a lack of request for radical change, and in that, there's an inference that people are accepting of the basic placement of enforcement as it is," Delany said. "I found that sometimes I need to be cognizant of the middle road nature of how a lot of people view this stuff."

In the coming months, high-profile cases that have dragged on for years (North Carolina and Ole Miss) may finally reach resolutions. Administrators around the country are closely watching the UNC academic fraud scandal given the potential competitive advantages the Tar Heels gained by fake classes over decades and the NCAA's mission to promote education.

"I think we're all curious about how that plays out," MAC commissioner Jon Steinbrecher said. "I think it will set some precedent moving forward. It gets into are the classes legitimate or not, and what is the ability of the NCAA to deal with that type of situation?"

The NCAA handles far more smaller cases that attract less attention. But like it or not, high-profile cases like North Carolina and Ole Miss shine a light on the NCAA's values and ability to police itself.

"I think a lot of the public feels that the staff and [infractions] committee leave the big schools alone, and go after the easier targets. It's not true at all," said Nebraska faculty athletic representative Jo Potuto, a former chair of the infractions committee. "In some ways, the public sees NCAA enforcement as a paper tiger -- that it would like to do more and has its hands tied and can't do more."

So what's working and what's not with NCAA enforcement in the three years since the model changed?

In recent months, three-year reviews have also been issued by the NCAA enforcement staff (the investigators) and the infractions committee (the judges). CBS Sports talked to some key decision-makers who are familiar with enforcement and penalties.

Most administrators interviewed for this article would not comment on specific cases and their remarks referred to topics generically. They all praised the work by NCAA vice president of enforcement Jon Duncan, whose staff has produced a steadier flow of cases. And they all have thoughts about a process the public loves to hate.

Outsourcing NCAA enforcement

In Delany's eyes, the Russian doping scandal at the Rio Olympics shows why the NCAA needs outside help to crack down on cheaters. The International Olympic Committee and the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) blamed each other over the fallout that revealed state-sponsored and widespread doping in Russia. There are now cries for a truly independent organization that's properly staffed and funded to punish offenders.

In a sense, WADA reflects how NCAA enforcement works since it's driven by peers. The NCAA members establish rules of what can and can't investigated. After an investigation by an independent NCAA enforcement staff, the members decide the penalties.

"One of the things talked about in the aftermath of Rio is should any entity that has marketing and promotional responsibilities also have enforcement responsibilities?" Delany said. "That's the case for outsourcing. But there's a lack of comfort with that because there's always tension. Everybody has the answer until they're under the gun, and then they want to be able to influence the instruments either through good defense work or challenging the people bringing the cases. That's the tension inside a system where you're being judged by your peers. That tension doesn't exist nearly as much when you have outsourced and cut the political tentacles that tie the peer to the adjuratory system."

Recommendations to NCAA

Opting against radical changes, Delany said the CCA made these recommendations to the NCAA:

- Don't spend money and time on violations that aren't fundamental in the eyes of NCAA members. Sort cases well so the most serious ones get the most attention from investigators to develop the facts.

- Because a university's reputation is so important, if a school is being attacked, make sure it's for a good cause with sufficient evidence. There's a belief the NCAA sometimes gets off track with narrower cases that hurt a university's reputation but don't involve fundamental mistakes by the school.

- Make sure wrongdoers are held accountable in a reasonable amount of time, understanding that cases can be delayed for various reasons. Provide more transparency on charging standards so there's some sense of a beginning and an end.

- Create a neutral ombudsman that can provide clarification to the school or enforcement staff during the investigation. For instance, the ombudsman could handle questions about timing, how evidence was obtained, and whether schools are living up to the NCAA's expectation of cooperation in cases. The ombudsman could provide a preliminary signal without unnecessary delays.

Length of investigations

The average NCAA investigation in 2015 took 7.8 months, down 9 percent from two years earlier, according to the NCAA. The NCAA's case load increased 26 percent over that period. Duncan said the enforcement staff is making informed projections about cases earlier, meaning unsubstantiated or less significant matters can be closed or processed faster.

Still, there are concerns about how long cases drag out. The Ole Miss investigation started in 2012. North Carolina's case has been on and off since 2011, when the NCAA passed on the academic questions initially and later reopened the case in 2014.

"People have talked about institutional reputational harm [due to lengthy investigations]," said SEC commissioner Greg Sankey, who chairs the Division I infractions committee. "But I'm also concerned that when issues arise and we take years and years and years to get at the issues, it sets a tone for the rest of the membership that maybe they can try some things but maybe it will take some time to catch up [with penalties]."

Universities often hire highly-skilled attorneys whose whole mission is to mitigate the damage. Duncan said the vast majority of cases are more collaborative than combative and the NCAA has positive relationships with these attorneys.

"Some schools and coaches are reluctant sometimes to hire counsel because they view it as an act of aggression and as a combative approach," Duncan said. "We don't view it that way. We welcome counsel to the infractions process."

Still, there's skepticism. "I think Jon has done a good job of leading the organization," Big 12 commissioner Bob Bowlsby said. "I continue to believe that in most of the major cases they're outmanned in terms of the tools they have at their disposal and even the representatives."

Sorting through 600 tips

The NCAA enforcement staff has 57 employees who receive about 600 pieces of raw information each year. Most of the information doesn't warrant an investigation, but sorting the tips is important and labor-intensive.

Since 2013, the NCAA said changes have reduced the length of this phase from an average of 60 days to three days. The length of time needed for additional research about tips has been reduced by 50 percent since 2014.

In the past three years, the Division I infractions committee concluded that 94 percent of the alleged violations cited by the enforcement staff occurred. The committee agreed 89 percent of the time with the severity of the violations, which range from Level 1 (the worst cases) to Level III. In the past three years, the NCAA as of August had alleged 182 Level I or II violations across 47 Division I cases, and processed over 10,000 Level III violations.

Duncan acknowledged that members can be frustrated by violations appears to go unpunished because the NCAA knows far more potential instances of wrongdoing than what they can prove. Duncan said he's concerned about those instances "not to get a pound of flesh," but to satisfy the mission of protecting the games.

"Maybe that means just letting institutions know that we know more than we can bring," Duncan said. "Maybe it means sanitizing these cases and sharing them with the coaching community and athletic director community or coaching associations, and without naming names, say these are the kinds of cases and specific instances we're tracking on."

Increased immunity

Attorneys who have worked NCAA cases for years say privately they think immunity is being granted more frequently by the NCAA. Immunity is valuable since the NCAA lacks subpoena power. It can absolve a player or coach of NCAA violations in order to secure information to help with cases.

Recently, the attorney of former Tennessee and Southern Miss basketball coach Donnie Tyndall claimed a former Southern Miss assistant cut an immunity deal with the NCAA after he lied about his own conduct in two previous interviews. Tyndall is challenging his 10-year show-cause penalty for academic fraud penalties in his program. In the Ole Miss case, Yahoo! Sports reported NCAA investigators granted immunity to players at three SEC West schools in exchange for truthful accounts of their recruitment by Ole Miss.

Speaking generically, Duncan described immunity as "a powerful tool" and said the NCAA doesn't keep numbers on how often it's granted. In cases that result in a notice of allegations, "it wouldn't surprise me if that (immunity) number is in the 25 percent category," Duncan said.

To get immunity, the enforcement staff must get permission from the infractions committee. There's virtually nothing in the NCAA bylaws about the standards for granting immunity. The bylaws simply state immunity can't apply to an employee's involvement of unreported NCAA violations, future involvement in violations, or any action taken by a university.

"I don't have a bank of immunity papers we can pass out," Duncan said. "We have to go to the [infractions committee] and make a case for why immunity is proper."

How to handle academic fraud

I've explained in the past the NCAA's new definition of when it can investigate academics on campus. Meanwhile, North Carolina has used the NCAA's own past actions to argue the association has no jurisdiction over academic matters.

That raises an important question I asked several administrators to explain. What's the distinction between NCAA members wanting the NCAA Clearinghouse to scrutinize the academic rigor of recruits' schools and classes but not allowing the enforcement staff to do it on campuses? If it's OK to questions academics on the front end and it's OK to ban teams due to their Academic Progress Rate score, why is it not OK to examine the academic rigor of classes when called into question?

"The distinction is the members themselves are confident that their academic oversight is strong enough, and if it's not and we have cases when there's been fraud, we have the ability to step in and deal with it," NCAA president Mark Emmert said. "The issue with examining literally a handful out of the thousands of high schools out there is the members have said, 'Yeah, we want you to keep looking at schools where we're not sure they have the kind of rigor or expectations that we need.'"

Delany said my question is fair. He's in the minority who wants schools to admit whatever athletes they want academically as long as they sit out athletically as a freshman to adjust to academics in college.

"The point is we judge others about the quality of their offerings," Delany said. "We look behind [academic rigor on campus] some, but the first line of defense are the local faculties and faculty senates. Absent somebody alleging or showing that a course is not credible, do they go behind that? I know here in the Big Ten we would never really think about scrutinizing the majors at Illinois, Wisconsin or Minnesota. That's not to say we wouldn't be attuned to academic fraud."

Adjustments to penalties

The infractions committee has proposed adjusting the penalty matrix when violations are found. For instance, Sankey said eliminating 50 percent of a team's scholarships is too much.

"We've never been at a case at that level, but we've asked that question in planning meetings some," Sankey said. "At 50 percent, you're really at a point of crippling a program and impacting a lot of young people and opportunities. There may be more effective penalties rather than just establishing that as an expectation."

Potuto said she believes suspending coaches for violations seems to be a change that's working. "I think that will have some impact, but not if it involves the school," she said. "I still think some of the penalties are too low. I don't think a couple years [of NCAA changes] gives you enough of a picture yet."

Eliminate some NCAA rules

Even though the NCAA rulebook has been trimmed in recent years, there's still a belief there are too many rules that don't matter. "If a recruit is going to pick Nebraska because he got a recruiting email that had a video running through it, more power to him," Potuto said. "I don't think that's why they pick the school, yet we have all kinds of rules about that stuff."

Sankey said when NCAA members create rules they have difficulty determining whether they're enforceable. "Can they be overseen properly from an administrative standpoint?" he said.

Should Power Five conferences police themselves?

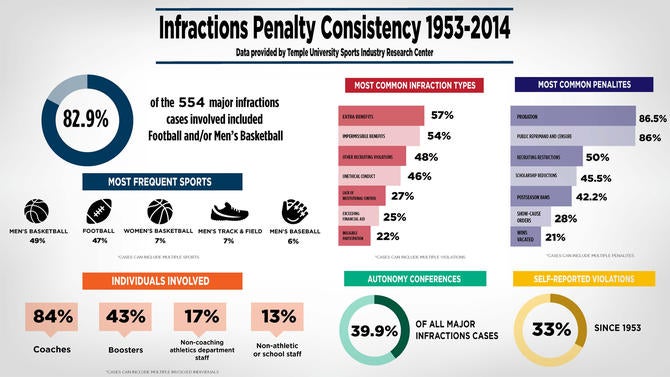

About 40 percent of all NCAA major infraction cases between 1953-2014 involve the five major conferences (SEC, Big Ten, Pac-12, ACC, Big 12), according to a recent Temple University study. That's a significant number attached to just five conferences. The study found that the Power Five leagues aren't punished differently in terms of probation lengthy, but they do get longer postseason bans in football.

NCAA members gave the Power Five autonomy in 2014 to create their own rules, such as cost of attendance, but not to police themselves in enforcement. "You're either an association or you're not," said Steinbrecher, the MAC commissioner. "I would hope that would not be the outcome."

Sankey opposes jumping to the conclusion the Power Five needs its own police system. "The notion that adults are challenged from an ethical and integrity standpoint to capture trophies and have national tournament participation opportunities is inherent across the division," he said.

Potuto believes the Power Five probably should enforce themselves due to the pressures, incentives and money attached with players through third parties. That's not the consensus opinion at this time.

"I don't think [the Power Five] achieved any common understanding of what we want if we wanted it," Delany said. "I think it could bubble up in a year or so, but everybody wants to see what we can get accomplished under the big tent umbrella."