Less than one week ago, during a nationally televised interview prior to the 2020 MLB Draft, commissioner Rob Manfred guaranteed baseball will be played this season. "We're going to play baseball in 2020, 100 percent," he said. That was not revelatory -- Manfred can unilaterally schedule the season, after all -- but it did make for a good soundbite.

Manfred's tone changed dramatically on Monday.

"I'm not confident (we can play)," he said during an ESPN interview. "I think there's real risk; and as long as there's no dialogue, that real risk is gonna continue ... It's just a disaster for our game, absolutely no question about it. It shouldn't be happening, and it's important that we find a way to get past it and get the game back on the field for the benefit of our fans."

Predictably, MLBPA executive director Tony Clark responded to Manfred's comments with a strongly worded statement:

"Players are disgusted that after Rob Manfred unequivocally told Players and fans that there would '100%' be a 2020 season, he has decided to go back on his word and is now threatening to cancel the entire season. Any implication that the Players Association has somehow delayed progress on health and safety protocols is completely false, as Rob has recently acknowledged the parties are 'very, very close.' This latest threat is just one more indication that Major League Baseball has been negotiating in bad faith since the beginning. This has always been about extracting additional pay cuts from Players and this is just another day and another bad faith tactic in their ongoing campaign."

In the span of five days Manfred went from guaranteeing baseball will be played -- "100 percent" -- to not being confident it can happen. That's quite the 180 in a short period of time. What changed? Three things, specifically.

Let's take a look.

1. The MLBPA stopped negotiating.

MLB submitted its latest return to play proposal last week but it was the same pig with a different shade of lipstick. The owners are willing to pay the players roughly one-third of their full season salary across some number of games. These have been MLB's offers:

- May 26: 82 games with a sliding salary scale (roughly 33 percent of full season salary)

- June 8: 76 games at 75 percent prorated pay (35 percent of full season salary)

- June 12: 72 games at 80 percent prorated pay (36 percent of full season salary)

The June 8 and June 12 proposals are conditional on the postseason being completed. If it's not, the players would receive an even smaller portion of their salary.

The MLBPA, meanwhile, has proposed 114-game and 89-game seasons at full prorated pay, so they've chopped 25 games (and 25 games worth of salary) off their initial proposal. They're making an effort. MLB's offers are relatively unchanged. They keep going back to the same place, and that's roughly one-third of full-season salary.

As a result, the MLBPA halted negotiations over the weekend, with Tony Clark saying "it appears further dialogue with the league would be futile." Clark invited Manfred to unilaterally the schedule the season, as the March agreement allows, and inform the players when to report. "Tell us when and where," Clark said.

That was the MLBPA's public statement. Privately, union negotiator Bruce Meyer sent MLB a letter demanding the league inform the players of their plan no later than Monday. "It is unfair to leave players and the fans hanging at this point. We demand that you inform us of your plans by close of business on Monday, June 15," Meyer wrote.

Clark's statement and Meyer's letter put the ball in MLB's court. The players are done negotiating, so it's up to MLB and Manfred to schedule the season. And, when that happens, they will have to explain why they're playing so few games (if they schedule 48-54 games, as expected) or why they didn't simply schedule the season sooner (if they schedule more than that).

When Manfred guaranteed the season will be played -- again, "100 percent" -- the MLBPA was still at the table and willing to make concessions as evidenced by its proposals. That is no longer the case. With the union no longer willing to negotiate, Manfred now is "not confident" the season can be played.

2. The chances of a grievance increased.

Once Manfred schedules the season, the MLBPA is expected to file a grievance arguing MLB did not make the "best efforts to play as many games as possible" as required by the March agreement. Case in point: MLB proposed as many as 82 games at one point, and the league may only schedule 48-54 games. That would seem to bode well for the union.

Presumably, MLB's defense will involve a clause in the March agreement stating the schedule will be created while "taking into account player safety and health, rescheduling needs, competitive considerations, stadium availability, and the economic feasibility of various alternatives." Such a grievance would not impact play and could take years to resolve, but it could result in MLB paying the MLBPA back pay.

For MLB, the downside to a grievance is enormous. The league could be forced to pay billions in back pay, obviously, and the discovery process may also require owners to turn over financial documents. Maybe not open their books entirely, but open them more than they are now, which would throw a huge wrench into the owners' claims that they're not making much money (like Cardinals owner Bill DeWitt Jr. and Cubs owner Tom Ricketts).

A potential grievance is apparently such a concern that MLB sent the MLBPA a letter on Monday informing the union it will not schedule any games unless the union waives its right to legal action. From the Associated Press:

MLB informed the union it would announce a schedule and a date for the resumption of spring training if the union agrees to waive claims that MLB violated the March 26 agreement between the sides or if the union agreed to an expedited grievance procedure. MLB said absent a solution, the dispute would remain an impediment to starting play.

Clearly, MLB is concerned about a grievance. I am no lawyer, but responding to a potential grievance that would argue you didn't play as many games as possible by threatening to play no games doesn't seem like a good idea. Maybe it'll work out for MLB. Who knows.

Anyway, the MLBPA would not have been able to file a grievance had the two sides agreed to a return-to-play plan. Now that the union is done negotiating and it's on Manfred to schedule the season, the union can file a grievance, and the case seems decently strong (I say that as a labor law layman). A grievance was not on the table five days ago, when Manfred guaranteed a season.

"Unfortunately, over the weekend, while Tony Clark was declaring his desire to get back to work, the union's top lawyer was out telling reporters, players, and eventually getting back to owners that as soon as we issued a schedule -- as they requested -- they intended to file a grievance claiming they were entitled to an additional billion dollars," Manfred told ESPN. "Obviously, that sort of bad faith tactic makes it extremely difficult to move forward in these circumstances."

3. COVID-19 cases are on the rise in some states.

Oh by the way, we're still in the middle of a deadly global pandemic, one that has infected over eight million people worldwide and killed over 118,000 Americans as of this writing. COVID-19 has not gone away. In fact, cases are spiking in many states, particularly in the south and southwest, which are home to many MLB teams. In addition, "several" MLB players and staff tested positive for COVID-19 recently, per the Associated Press.

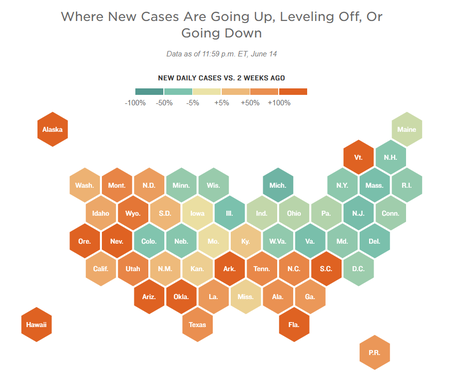

Here is a map showing new daily COVID-19 cases in each state over the last two weeks, via NPR:

Ignore the money and the ongoing labor dispute for a second. Is it safe to play major league baseball right now? There are no major health officials or government bodies saying MLB can not play, but is it safe? Beyond the players and the coaches, there are all the stadium workers and transportation folks, remember. There are tens of thousands in the cog that is the MLB machine.

We learn more about COVID-19 with each passing day, including which states have the most cases and which states are the best options to host professional baseball games. Increases in cases in the south and southwest affect one-third of the league and that's a problem. The pandemic remains a very real threat to the 2020 baseball season.

Canceling the 2020 season because it is not safe to play would be sad, but I think most fans would understand. Canceling a season because the owners can't convince the players to cover their losses though? That would be unforgivable. There is a chance MLB and the MLBPA are at war and destroying the league's image over a season that might not even be played due to the pandemic.

Baseball shut down in March because of COVID-19, though the shutdown has since morphed into a full-blown labor war. Again, there are no government agencies or health officials preventing baseball. It might not be a good idea to play, but spring training could be going on right now. Instead, MLB is threatening to cancel the season even though the commissioner guaranteed baseball will be played just five days ago.