COOPERSTOWN, N.Y. -- No event in sports brings a stronger sense of closure than a hall of fame induction. When a player, manager, or executive steps to the podium to deliver his speech, it's often the last major public act he'll perform in that sport.

Sunday's Baseball Hall of Fame inductions brought more closure, more finality than any in years... maybe decades.

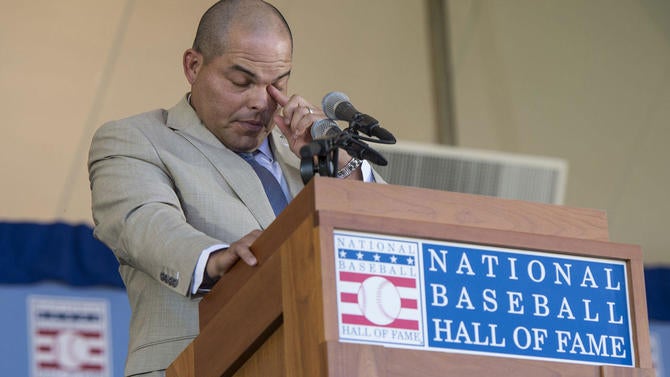

For Ivan Rodriguez, it marked the last time he'll ever have to hear accusations of performance-enhancing drug use, and giving even half a damn. The case for Pudge's use of steroids, and thus his exclusion from the Hall, boiled down to scraps of circumstantial evidence. Jose Canseco wrote a book in which he accused Rodriguez of juicing, just as he did numerous other ex-teammates. Pudge once answered the question of whether or not he used by saying "only God knows." He was extremely muscular, at a time when being jacked became more of a scarlet letter than a sign of health and fitness. When he showed up one spring training looking much slimmer, skeptics considered his weight loss a sign of guilt.

None of that mattered on Sunday. Pudge delivered an eloquent and heartfelt speech. He thanked his teammates and coaches and family, de rigeur for any inductee. But one of the great highlights of the weekend was watching fans of his teams cheering lustily for Rodriguez. One of those teams was the Texas Rangers, a recently successful franchise with a bit of a checkered history, having endured many seasons, and never won a World Series. The only player ever inducted as a member of the Rangers was Nolan Ryan, who made a far greater impact with the Astros and Angels. The other was Team Puerto Rico, and they were everywhere all weekend -- stuffing the aisles at the induction, singing songs and celebrating. When Pudge rolled through to close out the Saturday parade, he waved his Puerto Rico flag high, and hundreds of revelers responded in kind, serenading him all the way through.

Then Rodriguez punctuated his moving speech with perhaps the most inviting words anyone has ever uttered from the podium: "Don't feel intimidated to ask me for an autograph or a picture. You are not putting me out. It's my honor. Tell me your favorite Pudge story."

Jeff Bagwell experienced a similar sense of closure. The entire claim of Bagwell's supposed PED use rested on him once being skinny, and later becoming big. In the first place, this is a ludicrously thin non-argument. But beyond that, we've reached the point where we should close the book on pre-2006 players being denied votes, even if they did use. MLB didn't implement its Joint Drug Prevention and Treatment Program until the spring of 2006, so yes, the couple of decades leading up to that point amounted to a wild west of performance-enhancing drug use.

It's senseless to throw out a generation's worth of players and stats based on enforcement rules that didn't actually exist at the time, because MLB's owners and its commissioner happily looked the other way. If you want to bar Alex Rodriguez or Manny Ramirez for failing drug tests after the rule change, there's at least a tinge of logic behind that stance. Not so for the players who toiled before then, including Bagwell, who played his final game in 2005. (And again, was never found to have used anything illicit.)

By the numbers, Bagwell was one of the top six or seven first basemen of all time, and one of the top four to debut after 1900. Six years of numerical illiteracy and unfounded curmudgeondom finally ended, and thousands of bright orange-clad Astros fans got to celebrate their second Killer B induction in three summers, alternating chants of "Bi-ggi-O!" and "Baggy!" all weekend long.

John Schuerholz got his own proper sendoff for 50 years of baseball service. He broke in with the Orioles front office in 1966, working under Frank Cashen, Harry Dalton, and Lou Gorman. When Major League Baseball expanded to Kansas City, Gordman took Schuerholz with him to build the nascent Royals. Schuerholz took over as farm director and helped usher homegrown stars like George Brett and Frank White to the big leagues. By the late 70s, the Royals were one of the most talented teams in the league. By 1981, Schuerholz was the youngest general manager in baseball. And in 1985, the Royals won their first World Series. When the Royals started to dip, he jumped to Atlanta, replacing Bobby Cox as Braves GM in 1990. A year later, the Braves went from worst to first, winning the first of what would be 14 division titles in 15 years, including a World Series win in 1995.

Schuerholz told MLB Network that his induction speech was the first time in his half-century-long baseball career that he'd ever given a talk that was deeply personal, as opposed to professional. Yes, he discussed the great players he got to watch develop over all those years, and the great teams who achieved success under his leadership. But he also spoke of the bout of German measles that left him deaf in one ear at age 5. The moment during his junior year of college when he was abruptly told to stop dreaming of a career as a ballplayer and start thinking about scouting, and other player evaluation-based career options. He spoke of the honor of being inducted as an executive, thus taking his place alongside legendary operators like Larry MacPhail, Pat Gillick, and the great Branch Rickey.

Bud Selig's legacy is far more complicated, and it might take years (or decades) before the full impact of his tenure as commissioner is complete. Selig engineered baseball's return to Milwaukee, steering the faltering Seattle Pilots to his home state. Lacking the huge wealth that his fellow owners started bringing into the game, he kept the small-market Brewers afloat, eventually presiding over the powerhouse teams of the early 80s. Selig's tenure as commissioner also coincided with some extremely positive progress in the sport, namely a stadium renaissance, an explosion in television revenue, and the birth of the wildly lucrative MLB Advanced Media, all of which helped turned Major League Baseball into the financial powerhouse it is today.

Give Selig credit for his Brewers exploits. His tenure as commissioner, though, is far more complicated. First and foremost, Selig was the man in charge during the only season in which the World Series was ever cancelled due to a labor stoppage. Though the official cause of death was a players' strike, the owners -- supported by Selig -- forced the players' hand: Instead of agreeing to share revenue between large- and small-market clubs, they instead tried to dodge responsibility and reach into players' pockets for the cash. Selig's close friend and die-hard union-busting fan Jerry Reinsdorf led the charge, in the process depriving fans of the entire playoff schedule, as well as potential history-making chases by Tony Gwynn and Matt Williams.

There was more. Baseball's steroids epidemic exploded under Selig's watch, and he and the owners happily aided and abetted all of it, fixating instead on record attendance and revenue. There are plenty of baseball fans who enjoyed watching the epic home-run chase of 1998 as well as Barry Bonds' assault on the record books, and don't sweat the league's lax approach to PEDs. But to turn on a dime and become an anti-drug crusader, the way Selig suddenly did in the mid-aughts, defies all rational explanation. His behind-the-scenes efforts to ban Alex Rodriguez for life for embarrassing the commissioner during baseball's supposedly clean period resonated as particularly spiteful. Even the much-lauded stadium boom, aesthetically pleasing and good for business as it was, also saddled taxpayers with billions of dollars in debt. As for the sport's revenue explosion? If even a completely incompetent commissioner like Gary Bettman could be in power while the NHL filled its financial coffers, how much credit should we give Selig for being in the right place at the right time?

North of the border, Selig's legacy boils down to something much simpler: He killed the Montreal Expos. To be fair, this too is a bit of a distortion. The RICO suit brought by the team's minority owners near the end of the franchise's existence implicated Selig and former owner Jeffrey Loria as the masterminds behind an elaborate plot to steal the team from Montreal. That charge has never been proven, and even in the most charitable light is an exaggeration. Still, it's absolutely true that Selig was in charge in 1994, when the Expos held the best record in baseball, only to have power-mad owners like Reinsdorf (again, abetted by Selig) wreck the season in the name of short-sighted greed. The cancellation of that season set off a chain reaction that saw the Expos succumb to panic and give away the core of a magnificent and very young team for nothing the next spring. Selig's inability to engineer a proper revenue-sharing system fast enough fueled all of those events, and delivered a kill shot to a team that might've had the horses to smash the Braves' NL East reign, and possibly even the Yankees' dynasty of the 90s.

And while the RICO claim couldn't be proven, Selig was in the middle of multiple shady transactions that helped seal the Expos' fate. Those included over-the-top efforts to appease Loria, with giant loans from the league to help him buy the Marlins; a dubious agreement with John Henry to flee the Marlins and buy the Red Sox despite him not being the high bidder; and making the Expos wards of the league, then kneecapping the team by not allowing significant September callups during the club's last-hurrah wild-card chase of 2003. All of those actions left an incredibly bitter taste in the mouths of Expos fans that might never be fully extinguished. Many of those fans booed Selig during the Saturday parade, then turned their backs on him during his Sunday induction speech.

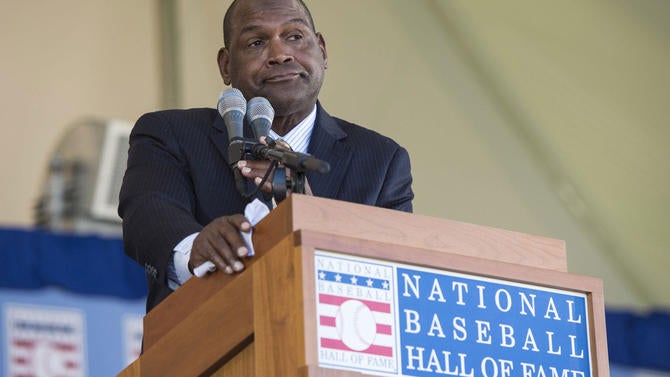

All of which brings us to Tim Raines, and to Expos fans.

Other than Ron Santo, perhaps no player in baseball history ever had a more frustrating path to the Hall of Fame than did Raines. His first time on the ballot was met with widespread apathy. Voters fixated on his lack of home runs and his inability to reach 3,000 hits. They ignored him being one of only five players to steal 800 bases, that he was the most successful basestealer ever by success rate, and that his keen ability to draw walks enabled him to reach base more times than Tony Gwynn, Roberto Clemente, and many other Hall of Famers. Less than one-quarter of voters saw the value in Raines' career during his first year on the ballot; even fewer voted for him in year two. Raines' candidacy started creeping higher over the years that followed.

Then, a huge setback. To appease the hysterical crowd of drug warriors who objected to Barry Bonds and Roger Clemens being on the ballot, the Hall implemented a new rule that gave voters just 10 years to decide on a candidate's worthiness, rather than the previous 15. A few players who'd passed 10 years of eligibility got grandfathered in and were allowed to go to 15. The player most affected by the rule change? Raines, who instantly went from having eight years of eligibility left to having three.

The three years that followed saw legions of Raines advocates -- Expos fans, baseball writers and statheads all included -- crank up the lobbying for Rock. In his 10th and final try, Raines finally got the votes he needed to punch his ticket.

That rocky journey made Raines' induction feel like the biggest sigh of relief for any of the weekend's honorees. Hordes of family and friends made the long journey from Florida to upstate New York to fete him. Multiple already enshrined players likewise paid tribute. Frank Thomas called Raines the best teammate he ever had, echoing a statement previously made by Derek Jeter and other luminaries. Andre Dawson spoke at length about Raines' infectious smile, the way his fun-loving demeanor lit up every clubhouse he ever entered.

On the podium, Raines spoke with a mix of humility, happiness, and awe. He paid tribute to Dawson, his close friend, the teammate he sought out when cocaine addiction threatened to ruin his career and his life, the man who helped him kick the habit and get back on track, the man for whom one of Raines' sons is named. He singled out Joe Morgan, the player Raines looked up to when his high-school baseball career in Sanford, Florida started to blossom. To go from emulating Morgan and other all-time greats to having them sitting behind you, acting as a peanut gallery while you choke back emotions during a speech in front of thousands of fans...imagine that.

Those Expos fans turned out in force. Their team ceased to exist 13 years ago. Today, there are no Opening Days to look forward to. No All-Star Games in which to hear the names of their favorite players called. No playoffs, no Hot Stove league, no rivalries, no highlight reels. All they have is nostalgia. They remember the great games, and the great players. With Vladimir Guerrero potentially going into the Hall as an Angel (or possibly with no cap, given his comparable contributions in Montreal and Anaheim), Raines' induction marked one last stand for fans of Nos Amours. Expos fans loved Rock for his talent and enthusiasm. They stood behind him when times were tough, and cheered forever when he came back to Montreal for an end-of-career cameo in 2001.

Watch this clip, and tell me Expos fans didn't love baseball. Tell me they didn't love Rock with all of their hearts. Tell me they didn't have this weekend in Cooperstown marked on their calendars for the past 15 years.

But for all the finality that induction weekend offered, you could still find hints of good times to come. On Monday morning, swarms of awestruck nine- and 10-year-olds flooded the Baseball Hall of Fame gift shop. None of them had ever seen Raines play. They weren't even alive when the Expos shipped off to Washington, D.C. Didn't matter. There they were, a day after Raines' induction into the Hall, begging their moms and dads for any and all Raines gear. Signed balls. T-shirts. Bobbleheads. Lego figurines. Anything to capture the moment.

For a player to go from little guy on the high school team in Sanford, Florida to permanent legend status, he has to touch a lot of lives. He keeps his teammates happy and loose. He impresses coaches and scouts. He intimidates opposing pitchers. He dazzles and shines and electrifies crowds everywhere he goes. He inspires the next generation of players to strive for greatness. And he pushes the generations to come to excel at everything they do, and to flash their own smiles when they do it.

The Hall of Fame's stated mission is to preserve the rich history of the game of baseball. Compelling so many young faces to light up over the exploits of men who starred before they were even born feels like an elaborate, incredible bit of magic.