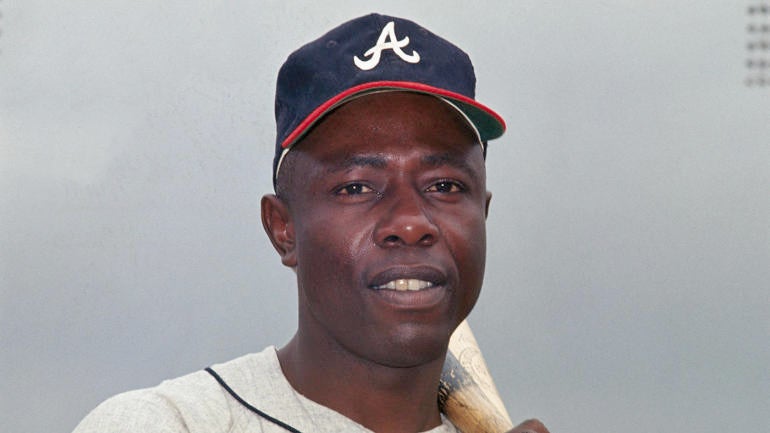

The baseball world suffered an immeasurable loss with the death of Hall of Famer Hank Aaron on Friday. Aaron, 86, finished his illustrious 23-year MLB career with 624 doubles, 755 home runs, 2,297 RBI, 2,174 runs, 3,771 hits and 240 stolen bases. His consistent excellence on the field made him an unparalleled baseball legend, but his civil rights activism -- which came during a time of deep unrest and racial tension and continued long after he left the game -- will forever be remembered as his life's greatest accomplishment. Aaron was equally as much an ambassador for the game of baseball as he was for racial equality.

Growing up in Mobile, Alabama, Aaron grew up in a segregated neighborhood with his seven siblings in a four-room house his father, Herbert Aaron built. Aaron shared stories of hiding under his bed from the Ku Klux Klan a number of times throughout his childhood.

"I remember many times as a little boy growing up that the Ku Klux Klan would come marching down the street, for no reason at all," Aaron said in a 2010 MLB Network interview. "My mother would tell me, 'Son, go hide under the bed.' The KKK would march by, burn a cross and go on about their business and then [my mother] would say, 'You can come out now.'"

When Jackie Robinson broke the Major League Baseball color barrier in 1947, Aaron was just 13 years old. When Robinson came to Mobile the following year to speak about segregation and what to do about it, Aaron skipped school to listen to him speak. The speech was what ultimately inspired Aaron to follow in the path of Robinson's baseball and activism.

Five years later, Aaron left Mobile to join the Indianapolis Clowns of the Negro Leagues. He'd play with the Clowns for one season, helping lead the club to the 1952 Negro League World Series title, before the Milwaukee Braves purchased him from the Clowns for $10,000. In 1953, Aaron broke the color barrier in the South Atlantic League with the Braves' minor-league affiliate, the Jacksonville Braves. They were one of the first integrated teams in the South Atlantic League.

"We were not able to stay with our teammates, we weren't able to change clothes in some of the ballparks with our teammates," Aaron said in that same 2010 interview. "You realized that they were not right, but by the same token you felt like you had to do them in order to make things better for someone else who was coming behind you."

Aaron continued to endure racism throughout the entirety of his baseball career, which lasted from 1954 to 1976. During his journey to passing Babe Ruth in all-time home runs, Aaron received relentless hate mail and threats to his life, solely because of his race and the fact that he was breaking a white man's record. He was forced to depart via the back exits of ballparks for the sake of safety, he needed a police escort with him most of the time and his children were subject to strict rules and limitations due to kidnapping threats.

"I got millions and millions of pieces of mail from people that were resentful simply because of the fact of who I was and they were just not ready for a Black man to break that record," Aaron said.

In 1994, as Aaron reflected on the 20th anniversary of his record-breaking home run, he told William C. Rhoden of the New York Times that "All of these things have put a bad taste in my mouth, and it won't go away. They carved a piece of my heart away."

As recently as 2019, Aaron again reflected on some of the darker times during his MLB career in an interview with FOX Sports South. "It was tough, Aaron said.

"Sometimes you sit down and you want to cry about it, you think about it and you say what did i do to make people have this kind of hate toward me. For a year and a half, I couldn't open a letter, they wouldn't allow me to open mail because every piece of mail I had was opened by Secret Service, people like that. It was hard, I had to go into the back of the ballparks instead of going out the front of the ballpark. Tough situation for me, for a while."

At the time, Aaron, like several other professional Black baseball players, was forced to endure the racism and hatred because fighting against it in any other way could have resulted in a serious threat to his life or the life of his family and close friends. Aaron spent 13 years playing professional baseball before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex or national origin. It would then be another year before the Voting Rights Act of 1965 -- a piece of federal legislation that prohibited racial discrimination in voting -- was signed into law. The sting from those harrowing memories lingered on for Aaron many years after his baseball career ended.

"I don't think about it that much just because of the pain,' Aaron said in a 2014 interview with USA Today. "I think about other things. There were other things in my life that I enjoyed more than chasing the record. I was being thrown to the wolves. Even though I did something great, nobody wanted to be a part of it. I was so isolated. I couldn't share it."

But, still, Aaron continued to use his baseball career as a platform to champion civil rights. He continued to lobby for efforts to encourage more young Black athletes to stay in baseball, he became the first Black American to hold a senior management position in baseball as a front office executive with the Atlanta Braves, supported the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and he founded the Chasing the Dream Foundation to support underprivileged youth with mentoring and financial support.

"I think that people can look at me and say, he was a great baseball player but he was an even greater human being," Aaron said in the same 2010 interview.

In 1982, his first year of eligibility, Aaron was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. He received 97.8 percent of the vote, which was second-most at the time only to Ty Cobb, who was inducted in 1936.

"I feel especially proud to be standing here where some years ago Jackie Robinson and Roy Campanella proved the way and made it possible for Frank [Robinson] and me and for other Blacks hopeful in baseball," Aaron said in his Hall of Fame Induction speech. "They proved to the world that a man's ability is limited only by his lack of opportunity."

President George W. Bush awarded Aaron the Presidential Medal of Freedom for his civil rights-focused philanthropy and humanitarian endeavors in 2002. The Baseball Hall of Fame opened a permanent exhibit in 2009 chronicling Aaron's life.

The impact of Aaron's life goes far beyond the baseball diamond. One of Aaron's final public acts was getting the coronavirus vaccine, alongside his wife, Billye, former U.N. Ambassador and civil rights leader Andrew Young and former U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Louis Sullivan. The goal of Aaron's public vaccination was to inspire and empower Black Americans -- who may have skepticism due to historical medical abuse and discrimination -- to do the same.