The Boston Red Sox announced Wednesday that they had fired manager John Farrell, after five years, three division titles, and a World Series championship. A day later, we still have no idea why they fired him.

Ace Red Sox beat writer Tim Britton did offer a lot of context to try to explain the firing. Britton noted some problems connecting with a team that was considerably younger than the one he inherited in 2013, en route to that World Series crown. He also cited some problems that might fall under the heading of bad optics -- including David Price's feud with broadcaster Dennis Eckersley, Pablo Sandoval using Instagram during the game, and the fallout from Manny Machado's hard slide into Dustin Pedroia in April. But Britton was quick to add that none of those headline-grabbing incidents derailed the team's success, as the Sox went on to their second straight 93-win season, and second straight AL East title.

If writers struggled to find a definitive answer, that was because Boston's general manager didn't offer anything close to one. In a Wednesday press conference, Dave Dombrowski was aggressively vague in explaining why Farrell is now unemployed. "At this point, sometimes change can be better, and that's why we decided to move forward with the change. You make moves because you think it's the best for an organization in that particular time. I'm not going to get into anything beyond that other than [there is] a lot of different factors." Dombrowski went on to add that Boston losing in the ALDS this season and last wasn't a major factor in his decision.

There's an obvious reason why Dombrowski didn't go into more detail. It's because the entire process by which teams hire, evaluate, and ultimately fire managers is opaque and deeply flawed, steeped in trusting one's gut and lacking in hard data. On the firing side in particular, we hear vague platitudes like how people felt it was time for a change.

In the meantime, if people were being honest, they would simply say this: Managers' jobs are nearly impossible to quantify, teams make rash decisions based on outside factors like media reaction and the griping of a few disaffected players, and nobody really knows what they're doing. When it comes to understand the value of managers, all of us -- fans, the media, players, general managers, and team owners -- are just engaged in one big Kabuki play. And when it comes to watching managers in the playoffs, we all lose our damn minds.

Consider Game 4 of the Nationals-Cubs series, and the wailing that occurred when it looked like Nats manager Dusty Baker might start Tanner Roark over Stephen Strasburg. When that game got rained out on Tuesday, the masses assumed Baker would go to Strasburg on full rest, thanks to the extra day off. Instead, he initially chose Roark. A relentless barrage of howling ensued. How could Baker not use one of the best and hottest pitchers in that spot? We soon learned that Strasburg was seriously under the weather. This didn't stop the complaining from peeved pundits. After disagreements at various levels that either represented genuine dysfunction or simply an elaborate bait-and-switch, Washington did go with Strasburg...who fired seven incredible innings of 12-strikeout, scoreless ball to pace a 5-0 victory.

All that consternation, and Strasburg started anyway. But even if he hadn't, how much difference would that have made? The Nats needed to win two more games to win the series regardless. So Strasburg was going to start one do-or-die game regardless, then cede the other start to one of the team's lesser starting pitchers. At first glance, Gio Gonzalez and his 2.96 ERA this season starting in Game 5 looks much better than Roark putting up his 4.67 ERA in Game 4. Except Gonzalez benefited from one of the highest strand rates in the league and other sources of good luck, while Roark was unlucky in several respects. Evaluate each pitcher by fielding-independent pitching, which focuses on outcomes a pitcher can best control (strikeouts, walks, home runs), and the two were nearly identical, with Gonzalez at 3.93, and Roark at 4.13.

This wasn't the only instance of the series in which critics declared Dusty Baker to be bad at his job. In Game 3 of the series, Baker pulled his ace Max Scherzer after 6 1/3 scoreless innings. The Cubs immediately tied the game against Nats reliever Sammy Solis, and went on to win 2-1. But placing the blame on Baker ignored multiple factors. First, Scherzer was coming off a hamstring injury, was for a long while was no sure bet to start the game, and wasn't a sure thing to keep firing zeroes given his long layoff and the state of his leg. Second, the Nationals managed just one run on three hits in that game, with the top four hitters in the lineup combining to go 0 for 16. Yet rather than discuss how tough it is for a team to win with such anemic offensive production, and rather than give a little more thought to the Strasburg dilemma, we jump to conclusions.

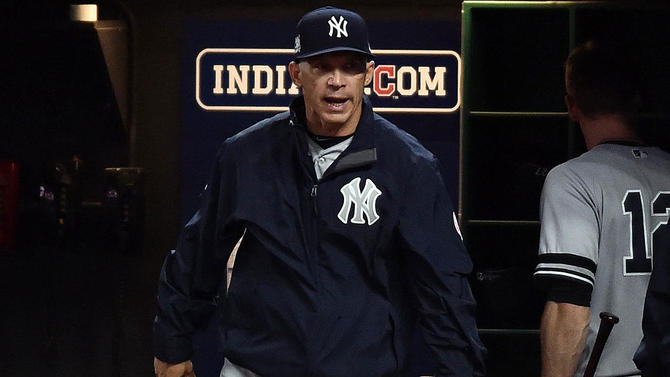

We see this type of situation play out in other playoff scenarios too. We lambaste Joe Girardi for his decision not to challenge a key call in Game 2, then rush to proclaim that he should be fired. But we ignore how the Yankees have fared in his 10 years as manager. That tenure includes a 2013-2016 stretch in which New York only made the playoffs once... but did so with the last gasps of an aging core, and all the makings of a team that could have been stripped for parts as part of a total teardown. Instead, they never won fewer than 84 games, and stayed competitive until the Baby Bombers emerged. Meanwhile, three games later, the Yankees have clawed their way back, pulled off one of the biggest upset comebacks in recent history, and now fly to Houston for the ALCS.

We fixate on in-game tactics because they offer us instant feedback -- either success or failure. Meanwhile, we have no idea how to objectively evaluate the most important job of a manager: to keep his team motivated through the gruelingly long 162-game season. As fans, we have no idea who's best at that role, who's worst, and who's in between. Even beat writers only see what they're able to see during open-clubhouse periods and other quick peeks. Hell, can we even trust any individual player with perfect certainty? The star shortstop might get different treatment than the mop-up reliever. And the cranky second baseman might simply start spreading rumors about clubhouse dissent because he woke up on the wrong side of the bed one day.

These are our flaws as human beings. We seek out simple explanations, when the situation might require far more rigorous analysis. We search desperately for scapegoats, ignoring the coin-flip aspect of the playoffs that can turn Corey Kluber from a Cy Young front-runner into a postseason punching bag, and other wildly unpredictable outcomes that happen when we play best-of-five series, instead of the best-of-155 matchups that would be more likely to reward the more talented team.

The notion that there's an easy explanation or person to blame for every postseason letdown is silly. Kerry Wood got hurt on Dusty Baker's watch a bunch of years ago, so now we question his acumen on handling pitchers forever more, ignoring extenuating circumstances (Wood got ruthlessly overused in high school, pitchers get hurt all the time, and Baker's mistake in Game 3 was, we were told, being too cautious). Cleveland's best pitcher and three of their best hitters went ice-cold for a week, and now we have to ask probing questions about whether 22-game winning streaks might actually be bad. Managers get canned for reasons roughly akin to "a ball hit a pebble and bounced over the third baseman's head", because columnists have stories to write, fans have teeth to gnash, and GMs have itchy trigger fingers to satisfy. If a Fortune 500 company were run as erratically as baseball teams are when they roast or even fire managers for nebulous and specious reasons, that company would go under inside of three years.

Far more than in any other sport, baseball's playoffs are as close to random as you'll ever see. The best team often loses. Wild cards can and have won it all. Momentum going into the playoffs means absolutely nothing. It's scary as hell to imagine a world in which dumb luck -- players suddenly going hot (or cold) at exactly the right (or wrong) time -- would decide championships. But that's baseball.

If you want to blame Baker for batting Jayson Werth in the ultra-valuable number-two spot, only to watch him come up empty in multiple big spots, go nuts. If you want to fault Girardi for sitting on his hands during that Game 2 decision, while also acknowledging that he has his strengths as a manager, have at it. If Dombrowski truly made his decision after months of deliberation, for reasons that went well beyond the Sox losing to a more talented team, mazel tov. As long as we all remember that shit happens in the playoffs. And that many other factors are more likely to decide the outcome of a game than whatever a manager might do from the bench.