After the Browns left Cleveland, a man paid $2,700 for Art Modell's toilet. The commode was on sale because of what happened on November 6, 1995. On a crisp, sunny, 55-degree morning in Baltimore, Modell stood behind a podium in a parking lot next to Camden Yards and made official a rumor that had been swirling for days: Cleveland's Browns would move to Maryland.

Unlike the governor, the mayor, and the preceding muckety-mucks in Baltimore who were overjoyed to land an NFL team, Modell seemed measured, even glum. "I am deeply, deeply sorry from the bottom of my heart," he told reporters from Cleveland.

Players had a bleak response when Modell came to a team meeting in Cleveland to break the news.

"Silence fell over the meeting room," says Antonio Langham, a cornerback on the 1995 Browns. "Guys didn't say anything. They were staring into space."

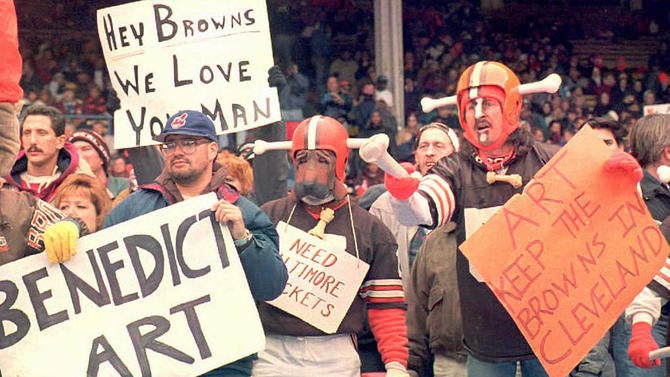

"Muck Fodell" became a rallying cry among fans at the remaining home games. Team sponsors fled. City leaders said they'd fight to stop the move. Next came court orders ("This isn't the Dawg Pound, it's a court of law," a Browns lawyer once remarked), rallies, arguments over the term of a lease, and finally, a settlement. Cleveland got to keep the Browns name, the history, and the colors. City leaders later were able to wrangle a promise from the NFL to bring a team back to Cleveland in 1999. As part of the deal, a new stadium, full of money-minting skyboxes, would rise up where the old stadium had long stood.

That led to an auction on a cold, rainy, windy day in September 1996. Its purpose was to get rid of as much stuff from Cleveland Municipal Stadium as possible before its demolition later that year.

Everything was for sale. Sections of wooden seats. Browns and Indians signs and flags. Ticket boxes. Urinals.

An amusement park bought 32 turnstiles for $350 apiece. A hot dog vendor bid on his old aluminum case. Gary Bauer, who owned The Basement nightclub in The Flats, plunked down $2,000 for Bernie Kosar's locker. He also bought the toilet. It came from Modell's owner's box. It was brown.

Bauer told a newspaper reporter that he planned to hang it from the ceiling of his club. The $2,700 price tag was worth it, he said, because this was no ordinary toilet. "I wanted to see where Art Modell made all his bad business decisions," he said.

If Modell was bad, what came after him has turned out to be much worse. Cleveland got an NFL team, but even though the Browns wanted you to feel as if they had never left, in a way, they never came back.

In the 16 seasons since their return, the Browns own the NFL's worst record. They've had just two winning seasons and one playoff berth, which came in 2002. And yet the support is still strong. In a way, Art Modell's toilet is the a perfect symbol of a fan base willing to visit the same old bowl on a regular basis, and expecting it to be filled with something different.

Except that, after the auction, the toilet was seemingly never heard from again. This seemed odd, especially in Cleveland, where hating on Art Modell quickly became a religious exercise, and an altarpiece like that would have provided reason enough to make a pilgrimage.

The Basement, a gritty place featuring cheap beer and teen nights in what used to be the alcohol- and youth-fueled east bank of The Flats -- where an ice luge for liquor was a mainstay, where women could flash bouncers to get to the front of the line -- probably didn't need the toilet to stay in business. It was one of many pieces of the messy garage-chic decor in the place. It was meant to stand out. Instead, it disappeared.

I had questions.

First off, where did the toilet go? How did a bizarre piece of sports memorabilia go missing? And, what does it say about a fan base that produces someone willing to pay almost three grand for something like that? After 20 years, does anyone really care about Art Modell anymore? Has Cleveland, at long last, moved on?

The answers would lead me to something more than the most infamous toilet in Cleveland. They cut to the heart of what it means to be a Browns fan in the modern era. The people I met in Cleveland and beyond all had one thing in common. They all grew up loving the Browns. But they all changed once the team they knew went down the drain.

The Best Seat in the House

It's still warm enough outside for Sean Walsh to sit outside with his buddy, Bob Magee. Walsh lives in a small house next to a tire store in the Old Brooklyn neighborhood on Cleveland's South Side. The back porch has seats from Jacobs Field and Crosley Field on it, along with a bleacher from Municipal.

Walsh and Magee go way back, all the way to 8th grade at Mooney Junior High in Cleveland. Walsh became a construction worker, Magee a fireman. They get together every few months. Both men are wearing Browns gear. Specifically, Walsh is wearing the same t-shirt and hat he wore to the final Browns home game in 1995.

Inevitably, they start talking about the team. Johnny Manziel deserves a chance. Hanford Dixon oughta be in the Hall of Fame. There aren't enough kids wearing Browns jerseys anymore. They're wearing Steelers jerseys now. In Cleveland! Can you believe that? Clay Matthews is still hanging around town. Mike Holmgren, in their estimation, "stole money." Brian Sipe was so good. Remember the time he threw that touchdown pass to Ozzie Newsome? Remember that? The conversation goes on like this for an hour.

Walsh loved the Browns so much that he was able to talk his way on to the demolition crew that tore down Cleveland Municipal Stadium in 1996. The place was rotted out, but it was still a fortress, built to withstand the withering wind, rain and snow that battered the stadium from its perch on the shore of Lake Erie.

It was built in 1931, and at the time, its 78,000 seats made it the biggest outdoor stadium in the world. It was one of the first publicly financed ballparks. The Indians started playing there in 1932. The Browns didn't come along until 1946. Before that, the Rams had played there, off and on, before leaving for Los Angeles in 1945. It was an imposing, cavernous, echoing place, built with black steel beams that obstructed views of the field. The yellow and beige bricks seemed to match the color of an overcast, industrial, rusting Cleveland.

The demolition took months. That was fine with Walsh. He wanted to see, one last time, the place where he'd spent so much time as a kid. He grew up seven miles away, wanting to be just like Leroy Kelly. As an adult, he wanted a turnstile. A ticket window. That was it.

But friends asked him if he could swipe some of the many seats that didn't sell in the auction. So he started taking them apart, slat by slat, section by section. And that's how Sean Walsh ended up with 300 Municipal Stadium seats in his backyard.

Walsh had been a small-time collector ever since he'd worked on the demolition of Comiskey Park in Chicago, and a foreman had given him a seat as a memento. He never thought anyone would actually want to buy and sell old seats on a large scale. He quickly realized he was wrong.By Christmas 1996, he'd already sold or given away 100 of them. Walsh drummed up sales by going on the radio in Cleveland, bringing breakfast to the morning hosts in exchange for a few moments of air time. Soon, people started calling from all around the country. The people who found him wanted a piece of authentic Cleveland history. They also asked Walsh if he could do something about the chipped paint and rust because, in some cases, the seats were going in their living rooms.

Walsh, now 53, is retired from construction, a job that allowed him to pluck chairs, signs and other pieces of soon-to-be-demolished ballparks and stadiums from all across the country. He now restores and sells seats full-time. A paintbrush, he says, is much easier on the knees.

Walsh has shipped Cleveland Municipal Stadium seats as far away as Guam. He sells them almost as soon as he gets them, usually for $399. They're not particularly pretty or unique. A Cleveland seat is practically identical to original seats from Fenway Park and Yankee Stadium, although the Yankees chairs retail for more.

Ballpark demolition has slowed down, and teams themselves have wised up to the fact that there's a market for all sorts of stadium memorabilia, which means Walsh has gone from ripping seats out to tracking them down. He finds them in barns and storage units, at estate sales and flea markets, and re-used in minor league ballparks. Years ago, he found them at a soon-to-be demolished church, where they'd been repainted and used as pews.

But even though the demolition led to a new career for Walsh, he still remembers the day Modell announced the move. The news made him sick. He pulls phrases from his own personal Browns glossary. The team didn't move, it was hijacked. The current Browns are a facsimile. Modell is called, on first reference, the devil. "I've never let it go," he says.

Magee remembers being at the firehouse in Berea when he heard the Browns were leaving. "Bob, calm down. It's not the end of the world," his captain said.

"Yeah, but it's close," Bob replied.

Since then, Magee says he's always skipped the Ratbirds game every year. It's clear which AFC North team that is.

Do Walsh and Magee still love the Browns? This facsimile put in place after the devil hijacked their team? Hell yeah. In fact, Magee feels a championship isn't far away. Probably not this year. But soon. "I really am certain," he says, before noting, "I've been wrong before."

Both men keep talking about the Browns in Walsh's garage, which smells like mineral spirits, and is full of chairs in various states of assembly. There's a Montreal Forum seat. Shibe Park. League Park. Comiskey. Fenway. Yankee Stadium. Downstairs in his basement, Walsh has set up a small shrine to seating. You walk through a turnstile to get in.

Today, those seats are some of the few things that remain from a stadium that was demolished, scrapped, and used to make an artificial reef in Lake Erie. Magee bought two seats last year. They're a physical reminder of a team that used to be good, and a symbol of hope that they could be again. "If the Browns are a disease, it's a good disease," Magee says. "Because we'll be the happiest people alive. Soon."

Cleveland's Rock

Drew Carey's son walks into the room.

"Connor, are you a football fan?"

"Uh yeah," Connor says.

"You watch it on Sundays?"

"Yeah. Barely."

"Barely," Drew repeats.

"But I do like the Seattle Seahawks."

"Ten years old. He likes the Seahawks."

Drew Carey is part owner of the Sounders, a Major League Soccer franchise based in Seattle, so this makes sense. Connor grew up with his father in Los Angeles, where Drew is in his ninth year as host of "The Price is Right" on CBS. He looks much different than the Drew Carey of 20 years ago. His glasses, there mostly for fashion and not for nearsightedness, are rectangular and no longer round. He sports a soul patch. He's lost more than 70 pounds. And he is no longer a rabid Browns fan.

That wasn't the case when "The Drew Carey Show" premiered on ABC. The sitcom, about a schlub living in Cleveland with oddball neighbors and an insanely over-madeup co-worker at a department store, was a hit early on.

Carey grew up in the same Old Brooklyn neighborhood as Sean Walsh and Bob Magee. His father died when he was 8. He joined the Marines after high school. After he got out, he started writing and telling jokes, hosting open mic nights in Cleveland, and performing around Northeast Ohio and Los Angeles. He appeared on "Star Search" in 1988 and got a perfect score. After his set on "The Tonight Show" in 1991, Johnny Carson invited him over to the couch, and called him "funny as hell."

Some of Carey's early standup jokes were about Cleveland's relative grittiness. Its drive-through liquor stores. The feet upon feet of lake effect snow that fall every winter. "A lot of my standup was about the little guy fighting back," Carey says. "That's the whole city of Cleveland right there."

He also made jokes about the Browns. If he knew he was doing standup in front of a lot of football fans, he'd ask the audience if they'd ever seen Bernie Kosar scramble, referring to the quarterback's notable lack of mobility. Then Carey would nudge the microphone stand, making it wobble until it fell over.

All of that Clevelandness went into his new show, which debuted September 13, 1995. The Browns announced their move less than two months later.

Carey's reaction was like that of many Browns fans. He was mad. And he didn't understand how a team with so much support could suddenly leave town. He flew home. He joined in and took the stage at rallies meant to try to convince Modell to keep the team. Carey felt like it was his duty. He never thought it would work.

In the meantime, his show picked up even more momentum. By season three, the show's opening sequence was changed to a music video set to Ian Hunter's "Cleveland Rocks," featuring Carey running down a street in downtown Cleveland, tailgating outside Jacobs Field in an Indians jersey, and dancing on a stage in The Flats. The new Browns wouldn't exist until season five, when the plot of an entire episode, shot on location in Cleveland, centered around getting tickets for the inaugural Browns game.

In real life, the new team asked Carey to come to the inaugural Browns game against the Steelers in 1999. On the field that day, he fired up the fans who saw him as a son of the city. "I want to send a message. A message to anyone who ever made fun of Cleveland. A message to anyone who ever told a Cleveland joke, or laughed at a Cleveland joke," he screamed out, "You can now, officially, shut up."

The Browns lost to the Steelers, 43-0.

By then, though, Carey wasn't the fan that he once was, the kind that would cry after a bad loss or let a loss on Sunday put him in a bad mood on Monday. He got along just fine without the Browns. "I found out then that I didn't need football," he says. When he was growing up, the team seemed to be woven into the fabric of the city. After they left, football just felt like a money grab.

That apathy started to turn to anger over the amount of public money being spent on the Browns. Carey joined the board of the Reason Foundation, and met with local politicians in Cleveland close to a decade ago to talk about some of the city's biggest problems. Schools were struggling. People were leaving.

But the first thing that the city council members wanted to talk about, Carey says, was the Browns. Since then, the city chipped in millions for two new 192-foot-wide, 40-foot-tall video boards that Carey noticed were suspiciously shaped like Tennessee, the home state of owner Jimmy Haslam. "I was like, f--- the Browns, man," he says.

Still, he's asked constantly about the team. He tends to give dry answers. How will they do this year? 8-8. What did you think about the Browns' new uniforms? I didn't think of them. And then, after enough snark, the question is always, I thought you were a Browns fan?

He still is. He goes to a few games, but pays his own way. He doesn't follow as closely as he used to, because he doesn't want the losing attitude to creep into his psyche. And he certainly doesn't feel the need to pass his Browns fandom on to his son. He prefers to talk soccer now, which inevitably leads to one more question: How did you become a soccer fan?

Simple, Carey replies. "You ever see the Browns?"

The Art of Betrayal

Michael White remembers everything that happened on November 5, 1995, and the days that followed. A day before the news broke that the Browns were leaving, a reporter from Baltimore was in Cleveland, asking questions. He'd been telling people that Modell would announce, the very next day, that the Browns would move to Maryland.

Michael White, Cleveland's mayor at the time, didn't give it much thought. He'd been talking with Modell about renovating the old stadium on the shoreline, and there was a $175 million tax issue up for a vote in two days to help pay for it. The reporter had to be wrong. "Boy, he's on some bad drugs," White thought at the time.

White recalled what happened next in a 2013 interview with teachingcleveland.org (He did not return requests for an interview for this story). The next day, he says, the calls continued. And later that morning, White realized there might be something to the rumors. Then he turned on the television. "I, like the rest of Cleveland, was sitting in front of the TV," he said, "watching Art Modell lie to us."

White flew to New York to meet with NFL commissioner Paul Tagliabue. After a 45 minute wait, White says Tagliabue basically asked him one question: How much is it going to take for you to go away? White's response: "There's going to be a lot of blood on the floor when this is over."

The short version of why Modell moved the Browns: The NFL's business model was changing. Corporate skyboxes, something Cleveland Municipal Stadium was short on, were becoming exponentially more lucrative than season tickets.

Modell bought the Browns in 1961 as a 35-year-old ad man. He got a sweetheart deal to run the city-owned stadium in 1974, one that allowed him to keep nearly all of the money he made there. He was the Indians' landlord. In the early 1990s, when Cleveland's politicians put together a plan to build a downtown arena for the Cavaliers and a glistening new ballpark for the Indians, Modell wasn't included. Whether he wasn't asked, or whether he turned down the city's offer for a new stadium is still up for debate.

Upkeep at the crumbling stadium went up. So did the price of players. Modell was millions of dollars in debt and losing money -- even with the NFL's generous revenue-sharing and salary caps, even as more than 70,000 fans showed up for every Browns home game, even while TV ratings in Cleveland were among the best in the NFL. Modell failed to evolve. So he moved. "I had no choice," he said.

White, a mayor described once as bookish, bearded, 5-foot-7 and not much of an athlete, a man who went to one or two Browns games a year, tops, thought Modell did have a choice.

He orchestrated a nationwide campaign to stop Modell. He met with other mayors. When Modell went to an owners meeting that year in Dallas, White held two competing press conferences. "We have been wronged," he said, over and over.

His trump card was a lease that Modell had signed in 1974, saying the Browns would play their home games in Cleveland Municipal Stadium until 1998. All of the maneuvers didn't stop the move, but they did help lead to the settlement that brought an NFL expansion team back in 1999 with the Browns name, history and colors.

After he arrived in Baltimore, Modell was less visible. He never publicly returned to Cleveland. Reporters said he never got over the move. And despite being one of the most influential and innovative men in the league during his time as owner of the Browns, Modell has been passed over by the Pro Football Hall of Fame. When he died in 2012, every team except for the Browns (at the request of Modell's son) held a moment of silence. In 2014, someone posted a video online of a Browns fan urinating on his grave. "I had no choice," the man said.

Michael White also left Cleveland. Three years after the Browns returned, White decided not to seek re-election, and decided to drop out of politics altogether. Today, he owns a winery and an alpaca farm in the hills outside of tiny Newcomerstown, Ohio, a two-hour ride from downtown Cleveland.

But even though he's escaped from the public eye, the Browns will always be part of his legacy. White said the fight wasn't about sports. Rather, it was one about the dignity of his community, and the battle seemed to draw everybody together. In that 2013 interview, the memory still feels fresh. "I think of that as Cleveland's finest hour," he said. And Modell? "You screw us, we're going to screw you right back."

The Brown who Came Back

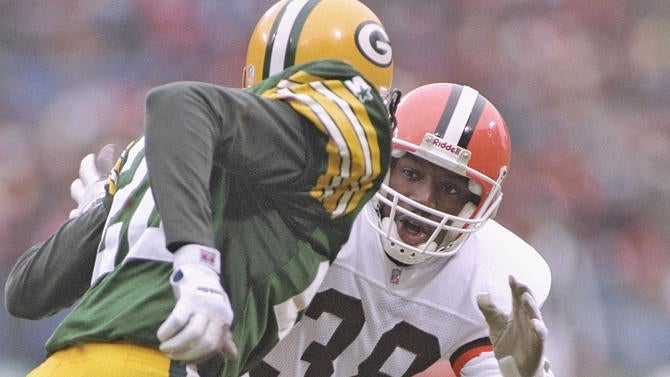

Antonio Langham saw everything firsthand. Twice.

Drafted out of Alabama in 1994, Langham had two interceptions and was the defensive rookie of the year in his first season with the Browns. He thought the transition from Tuscaloosa to Cleveland was easy.

Sure, the weather was bitterly cold during the season. But Langham had family in Northeast Ohio. Browns fans were as fierce and loyal as Bama fans. He bought a house in a new development in the southwest side suburb of Strongsville, not far from the Browns practice facility in Berea. There wasn't much to do there. He went to Perkins a lot.

Then 1995 happened. After the announcement, the Browns lost six of their last seven games. They won the last home game that year, 26-10 over the Bengals, and fans proceeded to tear the stadium apart, grabbing any mementos that weren't bolted down. Others lingered long into the night. Some players did too.

Langham knew stability was rare in the NFL, but he was under a four-year contract, and didn't think he'd be changing cities so soon. He and other players made the move to Baltimore that winter. Many of them lived in the same apartment complex.

They all had loose ends to tie up in Ohio. Kids in school. Houses to sell. It took Langham two years to sell his. (Same with Modell, whose Tudor-style mansion east of Cleveland eventually sold for $1.2 million under the asking price). By the time practice started, there were no Ravens jersey or hats -- or any kind of Ravens clothing -- to wear at practice. They wore stuff with Cleveland on it at first.

Steve Everitt would be fined $5,000 after he put on a Browns bandanna during a Ravens exhibition game. The lineman, who had a giant dagger tattooed on his back after the move was announced (reportedly to symbolize being stabbed in the back by Modell), said the bandanna was his way of saying goodbye to Cleveland.

Langham had his best year as a pro in 1996, with five interceptions for Baltimore. But he wasn't re-signed by the Ravens when his contract ran out after the 1997 season, and spent a tough year with the San Francisco 49ers in 1998.

Meanwhile, the league was rushing to put a team back in Cleveland. In the rush to bring the Browns back by 1999, the NFL bypassed an expansion process that usually has potential owners and cities competing with one another. Cleveland didn't beat out any other cities or ownership groups to get a team. It was handed one.

And so, Cleveland became complacent. "False Start," a book written in 2004 by local columnist Terry Pluto, makes a few more angrily stated points. The big one: The new Browns also had no time to prepare. In fact, no other team in recent memory had less time. The Houston Texans had 1,068 days between when their owner was chosen and their first NFL game. The Panthers had 677. The Buccaneers: 647. Cleveland? Just 369.

Pluto believes that the NFL waited because this was the golden era of stadium-building, and that at least five other teams used the threat of moving their team to Cleveland to squeeze new stadium deals out of their respective cities. The late start meant the 1999 Browns had to make slap-dash decisions.

Dwight Clark, the new Browns' first general manager, was merely supposed to be a guy who served as a go-between for the GM and coach. Then-president Carmen Policy told Pluto that Clark wasn't supposed to get the top job. Inaugural coach Chris Palmer wasn't hired until January 22, 1999. The expansion draft happened February 9.

On that day, Langham was out on the West Coast when he got the call. Congratulations. The Cleveland Browns took you with the last pick.

"Really?" Langham said.

Browns fans had never left. Their excitement was palpable. But Langham, now a veteran, was more cautious. This time, he rented a house in Strongsville. He tried to settle into his old routine. He drove the same old route to the same old practice facility. He went to the same old Perkins.

But it wasn't the same. The owner, Al Lerner, was different. The coaches were different. This wasn't a Browns team with a long history. This was an expansion team with the Browns name on it. Langham, now a veteran, wasn't happy with the decision to play young players instead of the best players. He didn't know his teammates very well. And he had to figure out the nooks and crannies of a new stadium.

"The biggest adjustment was trying to find the Dawg Pound," he says.

For the first time in his career, Langham finished the season without an interception. The Browns released him at the end of the year.

Langham retired after the 2000 season and now lives in Alabama. He always liked Art Modell, who would come to practice, invite Langham on to his golf cart, and ask how he was doing. He was one of the best owners in the NFL, Langham says. That, obviously, has not been a popular opinion in Cleveland.

Now, Antonio Langham is the answer to a trivia question: He's the only living player who played for the old Browns and the new Browns (the late offensive lineman Orlando Brown is the only other one who played for both incarnations). But he says even though the name was the same, he played for two totally different teams in Cleveland. "Trying to compare this team to what you had when you were there the first time," he says, "it isn't fair."

A Factory of Sadness

Mike Polk Jr. owns a Ryan Pontbriand jersey. He had it custom made in 2010. The woman at the team store didn't know who Ryan Pontbriand was. Still, Polk thought it would be a smart investment, because in his mind, the job of the long snapper seemed to be safely unimportant.

Position players come and go. But long snappers are anonymous enough to stay. Plus, the Browns didn't just sign Pontbriand, they drafted him, which is an exceedingly rare occurrence. Only 13 long snappers have been drafted since 1982. "I thought, well, shit, they're never going to admit a mistake by cutting this long snapper after wasting a draft pick on him," Polk says.

The Browns cut Pontbriand in 2011.

That November, wearing his Pontbriand jersey, after a 30-12 loss to the Houston Texans, Polk drove down to an empty Cleveland Browns Stadium, set up a video camera, lit himself with his headlights, and started shouting. He made a number of salient points. That it's statistically harder for a team to be this consistently bad than to occasionally accidentally be good. That fans have comically low expectations. And that the stadium is a factory of sadness. His list of complaints ends with the perfect summation of what Browns fans plan to do about all this: "Ehh, I'll see you Sunday."

That video has 1.8 million views and counting on YouTube.

Polk talks about how the video came together from a sidewalk table in front of Flannery's on E. 4th Street in downtown Cleveland. His voice cuts through the loud white noise of traffic and construction going on nearby. There are plenty of people walking by at lunchtime. One sees Polk, and without breaking stride, yells "Mr. Haslam!"

"I do an impression of Jimmy Haslam on the sports show," Polk says, which he admits is basically just Will Ferrell's impression of George W. Bush. "Word is, he's not a fan."

Polk now has regular segments on the local Fox affiliate in Cleveland, which is an outgrowth of his regular standup gigs, and more recently, his YouTube videos. A few minutes later, he tries to explain why Haslam, a travel plaza magnate and current Browns owner, is going about things all wrong.

"They come in looking at this like it's a failing gas station," Polk says, and then he turns on the impression: "I've turned around gas stations before. It's not hard. I had trouble with one I remember in Little Rock. I went down there, made some changes, put a paint job on it, and everybody's goin' there."

This is the cycle of life for Browns executives, Polk says. They consistently underestimate the level of fandom here. They get freaked out by the media coverage. They leave. Since 1999, the team has had seven general managers, and eight head coaches. "And we're still here when they're gone," he says.

The endless parade of incompetence makes for some easy jokes, which has been very good for Mike Polk Jr. He tries to avoid those jokes in his standup routines. They're just too easy. But if he starts losing the crowd, all he has to do is ask if there are any Browns fans in the audience. That can dig him out of a hole. The jokes work everywhere now, because, Polk says, "Our misery is nationally known."

Polk was 17 when the Browns left. His father had season tickets in section 34, and Polk would go when one of his dad's drinking buddies couldn't make it. He saw several sold out games first-hand, and remembers being baffled when he heard the team was moving.

"It was really an early lesson on how unfair life can be on a large level," he says.

Mike Polk cares about the Browns. To a point. He's a season ticket holder. The rage over the team's impotence puts him on TV regularly. But for the most part, he's changed. He's not as furious as people would prefer him to be.

Maybe it's because the Cleveland that Polk lives in is much different than the one the Browns left in 1995. Back then, downtown had only a few attractions, and closed up after work on weekdays. There was Tower City for shopping. That was about it.

It stayed that way for years, and it provided the fuel for Polk's most famous YouTube video, a 51-second clip he put together originally to show at an open mic night in 2007. He went downtown with a cheap video camera. "I started waving it around and saying nonsense lyrics on top of it," he says. The video starts with a peppy and cheesy music bed under it:

Come on down to Clevelandtown, everyone

Come and look at both of our buildings...

The Hastily Made Cleveland Tourism Video took two hours to put together, and the desolation is palpable:

Here's the place where there used to be industry

This train is carrying jobs out of Cleveland …

After that video took off, Polk made a second. But he hasn't put out a third. It just wouldn't be as funny, because it's no longer as true. It's much nicer downtown now. And there are more exciting things to do for young people now than there were in the 1990s, when the Browns were arguably the most exciting thing in town.

The city now has pride that doesn't HAVE to be tied to its football team. It started when the Indians, fueled by cash brought in by a series of sellouts in their new stadium, made two World Series runs. It happened later when the Cavaliers drafted LeBron James. And it happened again when LeBron came back.

Even beyond sports, a walk around downtown Cleveland is far different than it was in 1995. There is a casino, construction and revitalization. There is green space and museums. Young people are hanging out in front of restaurants and upscale bars on E. Fourth Street, which has been closed to traffic to make it feel more cosmopolitan.

There's a plan in the works to revitalize The Flats. Across the Cuyahoga, the old school West Side Market is the hub for new growth, including the Great Lakes Brewery. Even an old home in a working class neighborhood has become a tourist destination. People come from all over to visit Ralphie's actual house from "A Christmas Story."

There's a misconception in Cleveland, Polk says, that the entire town's happiness is tied to the Browns. Sure, there are a lot of loud, angry, blindly obedient, championship-starved fans (just listen to WKNR 850 for a few minutes and you'll hear from them). But the vast majority doesn't seem to care when national media uses its misery as a commodity.

"I don't speak for everyone," Polk says, "but we don't give a shit."

And yet, you can walk into a store downtown and find two coloring books on sale. Both depict a Browns fan sitting on a couch, in two vastly different moods. The workers there say "Why is Daddy Sad On Sunday?" far outsells "Why Is Daddy Happy On Sunday?"

Cleveland has come a long way. But as Polk knows, it's still good for a punchline when you need one.

Life Imitates Art

Outside of the Browns practice facility in Berea, practice is just breaking up. Fans wearing jerseys -- a few new and dark brown but mostly old and faded -- stream out onto the sidewalk along Lou Groza Boulevard. There's a clear line here, between generations of Browns fans. I have one question for them all: Do you remember Art Modell?

Two little girls, 8 and 10, say no as they munch on pretzels. Their moms say yes. "Everybody was mad," one of the mothers says. "We get over it."

Chris Huber, 29, says yes, he remembers. He was at some Save Our Browns rallies, and a few home games. I wonder if he thinks there's a difference between the old and the new Browns. "Some bad draft picks," he says.

Across the street in a parking lot, a gaggle of lanky 16-year-old kids clad head to toe in orange and brown are waiting for some players to drive out. Sometimes they'll stop and sign autographs. The success rate is low, but if the right guy stops, it's worth the wait.

I ask if they know who Art Modell is.

"Yeah," they all say, almost in unison, about a man who moved the team four years before they were born.

"He moved the Browns," one kid says.

"Hate him," says another one.

In the back, another kid, unprompted, starts rattling off the nicknames for the worst plays on Browns history. "The Drive… The Fumble…" he says. I asked who taught him this. His father, he replies. Misery, it turns out, can be passed down to a new generation.

I don't plan on passing that down to my son. I grew up near Warren, Ohio, about an hour southeast of Cleveland. I was a Browns fan. My father and I went to games. We watched "The Drew Carey Show." Thirteen years ago, we went to Sean Walsh's house and my dad bought a seat. We saw Bernie Kosar's last game as a Brown. The freezing cold made me lose the feeling in my toes. Another time, I sat in the Dawg Pound next to a man who'd lost a bet. He had to wear Steelers' gear. I had to dodge badly thrown Alpo cans and dog biscuits that were meant for him.

Three years after the Browns left Northeast Ohio, so did I. I went to college and kept moving south. I've never been to a Browns game in the new stadium. I made do, going to Browns Backers clubs in North Carolina, and getting upset on Sundays. I stopped going. They put me in a bad mood.

When people find out I grew up near Cleveland, they always ask me if I'm a Browns fan. I still say yes. But when they ask, my conscience keeps asking me a follow-up question: Why?

It's clear that other fans, mostly younger ones, are also starting to question their loyalty to a team that only ever seems to lose. They're increasingly tempted by the Internet and NFL Sunday Ticket, which make it simple to follow a winner somewhere else. But it's also clear that a lot of Browns fans are still living in gleeful misery. They were first blindsided by Modell, then numbed by losing, but consistently remain zombie-like in their support. They know no other way.

That question -- why are you a Browns fan? -- brought me back to Cleveland this summer. I wondered if, maybe, I'd just gotten everything wrong. That maybe, if I talked to enough people, I'd be able to either rekindle my love for this team, or find the right reason to abandon it altogether.

I didn't really have an answer by the time I decided to make one last-ditch effort to find Art Modell's toilet. The trail had gone cold. I couldn't find pictures of it online. I'd called phone numbers that nobody picked up. All I had was an address for the man who supposedly bought it. It was the end of a long day in Cleveland, but I decided to make the half-hour drive from downtown out to a condo complex next to a strip mall in the west side suburb of Avon Lake. I checked the address once again, and knocked.

Nineteen years after the auction, Gary Bauer opened the door, and sheepishly admitted that he no longer had the toilet. The Basement had long since shut down after several lawsuits over security. It and other bars were torn down to make way for more family friendly development along the Cuyahoga River. The Flats were once as rowdy as the fans in the Dawg Pound. Now, both are milder.

Afterward, most of what was inside The Basement ended up in a storage unit. About 13 or 14 years ago, someone threw the toilet out because it looked like a regular old toilet. That was it. That was how the strangest piece of Cleveland Browns memorabilia was lost forever. Bauer didn't have much to say. But his voice betrayed him. There's regret. His toilet is gone. His nightclub is gone. His team is gone. And I get it now. That era is over. And you can never get it back.

Jeremy Markovich is the senior writer/editor at Our State magazine, and has contributed stories to Charlotte magazine, SB Nation, and WCNC-TV. He lives in Greensboro, North Carolina with his wife, son, and dog. This is his first story for CBS Sports. Follow him on Twitter at @deftlyinane.