Before he met with Dan and Tanya Snyder and spoke with head coach Ron Rivera twice, and well before some of his best friends from his NFL playing days found out about his new role from media reports, new Washington Football Team president Jason Wright co-authored several reports for the McKinsey & Company consulting firm on racial inequity and economic exclusion In Black America.

Wright, who on Monday was announced as the first Black team president in NFL history, wrote in April about the disproportionate impact COVID-19 was having on Black people. He and his colleagues reported that "[f]orty percent of the revenues of black-owned businesses are located in the five most vulnerable sectors — including leisure, hospitality, and retail — compared with 25 percent of the revenues of all US businesses."

In February, just before COVID-19 reached pandemic levels, he made the case for accelerating financial inclusion in Black communities. The median income of a Black family is about one-tenth that of a white family, and his report notes that 47% of Black families are unbanked or underbanked "— a disparity that, over the course of a financial lifetime, can cost nearly $40,000 in fees."

I spoke to Wright by phone Monday and asked him how he's grown to better understand racial inequities over the years. And not just his lived experiences as a Black man, but how his post-NFL education at the University of Chicago's business school and his work in outreach to executives of color across the country have helped mold his thinking.

"It's a little bit of the management and leadership approach that I bring to business," Wright says. "No. 1 is surround yourself with really smart people. My collaborators at my former firm are some of the most brilliant minds on topics of equity and inclusion and inclusive growth in the world. And surrounding myself with those people and getting the right team in place is absolutely the most fundamental piece.

"Secondarily it's to take a data-driven approach. You notice in those reports there is a whole lot of data and numbers. It's important when even something that feels squishy or soft or philosophical like racial inequality, it can be dimensionalized. The same way that culture like the Washington Football Team can be dimensionalized. And that gives you a feel for the way I want to approach these things. We tend to pay attention to the things we measure. So it's important to measure the things that are most important. That is the thread that you see through my prior research, and it's a thread that you'll see through the way that we approach culture at the Washington Football Team."

Culture has been — and trust me, it will continue to be — the buzzword in the area formerly known as R*dskin Park. That was assured when Ron Rivera took the job in January. It was emphasized (and then re-emphasized for more emphasis) after the Washington Post revealed the team's miserable, toxic culture before Rivera made his way up I-95. And it's one of the main reasons Wright took this job.

But … why'd he take it? I mean, it's obvious why. There are only 32 of these, and unless you're the child of the team owner, you don't have a good shot. Before Monday, if you're not white, you had no shot at all.

If the allure was singular to becoming the first Black NFL team president, that wouldn't be good enough because he'd likely be the first Black NFL team president to be fired not long after. It's obviously more than that, and I asked him why he decided to trust that he and the situation would be different under Snyder when there's a graveyard of former Washington Football Team employees from the last 15 years who have thought the exact same thing.

"In those conversations [with Snyder] we didn't just talk about the rosy future. We talked about the mistakes we've made. I talked about mine. Dan talked about his. We were really transparent with one another," Wright says. "We asked each other provocative questions about tough topics. And the fact that we got to that level of transparency and openness really gives me a lot of confidence walking into this job."

Joe Thomas, the former Browns left tackle and future Hall of Famer, found out about Wright's gig while watching TV during his morning workout, which was odd considering they're in a text thread with other members of the 2007 Browns team and Wright never even hinted this was a possibility.

Once the shock subsided — and once Thomas left Wright an "appropriately inappropriate" video message about being left hanging, per Wright — Thomas quickly realized how well Wright's attributes as a sort of journey running back will serve him in the big chair.

"He played on all the special teams. But also he made the name for himself being the third down running back where you're in charge of basically being a sixth offensive lineman out there," Thomas says. "You occasionally catch the football and occasionally he'd get a carry, but for the most part he was in charge of being the running back who would sit in the offensive line meetings, talk about blitz pickup, put his nose in there and block Ray Lewis or Terrell Suggs coming off the edge.

"He was willing to do that work and I think when you're an undersized running back and you're willing to put in the time mentally and physically to be that third down blitz protector, you get a lot of respect from everybody, especially the guys on the offensive line seeing a 215-pound running back pick up guys that are the same size as me."

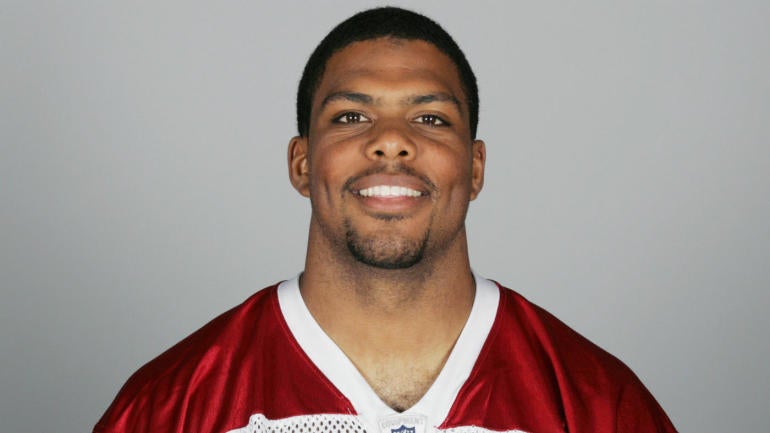

Wright was one of Jay Feely's "favorite teammates I ever had," the former NFL kicker and current CBS Sports analyst told me. The two overlapped on the Arizona Cardinals for the 2010 season and into the 2011 lockout, where Wright served as the team's union rep before retiring to go to grad school.

"With the issues that they've had there in Washington," Feely says, "with the name change, with the sexual harassment charges, you need somebody who comes in with impeccable integrity to bring credibility back to that franchise. Jason will absolutely do that. And then when you look at the fact that he's the first Black man to become a team president in the NFL, that's substantial.

"But the great thing is, regardless of his color, he absolutely was hired based on his merit, and his education. I'm sure when he did his interview he blew them away because that's the kind of person he is. When he'd engage with people on a daily basis in the locker room it was different. It was very intentional. That's the best way I could describe him and his relationships."

In the interviews with Snyder and Rivera, Wright started hearing the same words being used: inclusive, transparent, open and trusting. They spoke about what means for the football and business sides of the house, and he began to see how those shared values can manifest in a football franchise.

How specifically? "Ah, I can't give you the secret sauce, man," Wright says when I ask him what his 100 Days Plan is now that he's a president in Washington. But he did give a peak behind the curtain.

"We're going to move it to a place where there's a trust-based relationship among all colleagues," Wright says. "Where voices are empowered in the most critical decisions, especially women's voices, that shape the franchise because they should be but also because it makes good business sense. And we're going to have a transparent culture where we know where we're performing well, we know where we're not, and not to hold it over people in a negative way but figure out where we need to better invest.

"There are a broader set of things that need to happen. I need to meet people. It's critical for a new leader of an organization to talk to as many people as possible. And I'm for sure going to do that in my first 100 days. It's important to listen because culture change is going to happen at the individual level, and me understanding the state of the culture today is going to happen at the individual level."