In the hours Thursday after the announcement of the death of O.J. Simpson, the football legend who infamously was acquitted of criminal charges in a double murder, few wanted to talk.

The National Football League has provided no statement on the passing of the first player to rush for 2,000 yards in a season. The Buffalo Bills, who a day before wished Steve Tasker a happy birthday with an accompanying graphic on X, said nothing. The University of Southern California kept mum after one of its eight Heisman Trophy winners -- yes, eight, because we all witnessed the 2005 season with our own eyes -- passed away.

We know why this is. As one team executive told me Thursday afternoon, you would rather be criticized for something you don't say rather than something you do say. Any statement given in the wake of Simpson's death would be, quite literally, only a statement.

And that's just what the Pro Football Hall of Fame did on Thursday.

"O.J. Simpson was the first player to reach a rushing mark many thought could not be attained in a 14-game season when he topped 2,000 yards," Pro Football Hall of Fame president Jim Porter said in a statement. "His on-field contributions will be preserved in the Hall's archives in Canton, Ohio."

Simpson has been in the Hall of Fame since 1985. Legends die all the time, and never must it be made clear that their busts will remain. In the case of Simpson, for obvious reasons, it does.

"[T]he current Hall bylaws do not include any process for removal of an enshrinee once elected," Pro Football Hall of Fame Chief Communications and Content Office Rich Desrosiers wrote in an email to CBS Sports on Thursday.

The Pro Football Hall of Fame tells its voters to consider only what a player or coach did on the field. And once that person is in, there's no getting him out.

Of course, the Hall can always change its bylaws. The institution -- and, for that matter, any institution -- does not have to continue to honor morally deplorable humans simply because they were great at their profession.

Still, Simpson's bust doesn't even have to be removed. An acknowledgement of what the majority of Americans have always believed to be true -- that the great running back killed his ex-wife, Nicole Simpson, and her friend, Ron Goldman -- can coexist with his football accolades because we are an evolved-enough species to comprehend nuance.

But we also occupy a time in sports when, more than ever, we recognize players as being more than athletes. It's celebrated today that there is a person under the helmet who can make an impact beyond scoring touchdowns. It's encouraged.

If the American public were ever under the assumption that their favorite athletes were either infallible or one-dimensional, that concept has been shattered over the past several decades.

Even O.J. Simpson knew that four decades ago.

Simpson's induction to the Hall in 1985 came alongside New York Jets great Joe Namath. There, The New York Times quoted Simpson as praising Namath as a "real person" and a "Godsend for all us players" because fans could see players as people rather than as idols.

''People started to realize that players didn't always drink milk and eat apple pie,'' O. J. Simpson said, according to The Times. ''I remember reading Joe saying that he liked his women blonde and his Johnny Walker red. I loved that. And after that people started realizing that if we didn't hurt anyone, we could be ourselves.''

If the Hall's purpose is to only celebrate the greatness between the white lines, then there's very little reason to book your next trip to Canton. The Hall is a museum that should be dedicated to telling all the stories around pro football.

And it does just that. There are regularly exhibits featuring people around the game who did not do enough (or anything) on the field to be sized for gold jacket. The game can and should be celebrated, but not at the cost of truth.

Consider a topical example: Hundreds of confederate monuments -- rightly -- have come down by various judicial and extrajudicial means, but there are hundreds more standing across the country as defenders promote the vacuous notion that all records of chattel slavery will be erased if these Jim Crow era statues get toppled. However, those records of the past are not the goal of public-facing statues. They belong in museums, which are places civilizations across millennia have agreed is where we go to learn about the past -- not just our convenient past, but the entire past. And if there are artifacts within that exhibit with problematic provenance, well, that must be accounted for, as well.

The Hall is not exclusively a shrine; it's a museum for pro football's history. It doesn't want to become a place that arbitrates morality, and that's a reasonable wish. Simpson wasn't convicted of the murders, but even still according to the Hall's bylaws, there would have been nothing in place to throw him out of the Hall in 1995 if the Los Angeles jury had returned guilty verdicts anyway.

And then where does it stop? George Preston Marshall, former owner of what was known as the Washington Redskins, was one of the first people to be enshrined in the Hall. He was also a virulent racist, and one of the last, most important segregationists in pro football. In 2020 the Washington franchise removed him from the ring of honor, but his bust remains one of the first you'll see in Canton.

Jim Brown was a greater running back and actor than Simpson ever was. Brown is one of the greatest activists in pro sports history. He also was accused several times of abuse against women. To ignore his activism and abusive nature and only promote what he did with a football in his hands is intellectually dishonest.

But there are plenty of examples of the Hall struggling to maintain its football-only stance.

**

Darren Sharper made the 2000s All-Decade team with his two first-team All Pros and four more second team nominations. He won a Super Bowl with the Saints and led the NFL in interceptions in two different seasons.

Sharper is also a convicted serial rapist. Months after he pled guilty to drugging and raping multiple women across multiple states, he was one of 94 nominees for the Hall's Class of 2017. Sharper has not again been nominated for the Hall. And because a player's off-the-field life isn't supposed to be considered in the process, one can only conclude that his All-Decade play has, upon reflection, not been as impressive as it was when he was first eligible for nomination.

Right.

If one is truly to consider behavior between the lines, it is obvious that Terrell Owens is a first-ballot Hall of Famer. He was five-time first-team All Pro, led the NFL in touchdown receptions in three different seasons and retired trailing only Jerry Rice in all-time receiving yards.

When Joe Montana was up for induction, a writer stood up to present his case by simply saying: "Ladies and gentlemen, Joe Montana." Owens's case could have been even shorter. "Ladies and gentlemen, T.O."

Still, it took three ballots before Owens got into the Hall. And it was because of nebulous character concerns that may have impacted his teammates, which thus excused his exclusive for a couple of years. It was ridiculous then as it is now.

There are 50 voters for the Hall, which means there are enough people with enough common sense and basic morals to determine who should be inducted into the Hall. The people who are asked to evaluate what a player or coach did in the game relative to their contemporaries can also assess whether that person behaved in a way that aligns with societal norms. We don't have to pretend like life outside of football doesn't exist.

But it does introduce the concept of a slippery slope. And it is hard and can be made even harder. Now isn't the time to remove Simpson's bust from the Hall — and there may never be a good time — but adding some necessary biographical information in this museum during the football offseason shouldn't be considered too heavy of a lift.

Look at the Bills, who inducted Simpson to their Wall of Fame in 1980, well before any documented legal trouble. His name and number remain up at Highmark Stadium, something Terry and Kim Pegula inherited when they purchased the team in 2014.

As noted above, the Bills have been quiet about Simpson's passing. In 2026, they will begin playing at their new stadium. Perhaps they'll just happen to forget to include '32 O.J. SIMPSON' while decorating the new place. And who will really care if they remove Simpson from their wall of glory?

**

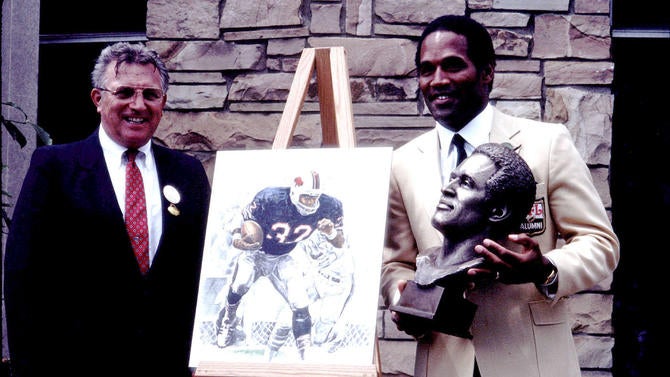

On Aug. 3, 1985, Simpson wove a great yarn in his induction speech. He could only have one presenter, and he picked former Bills coach Lou Saban to do the honors. But if he could have had a co-presenter, he would have chosen Jack McBride, who was his high school JV football coach.

The week of the JV championship, Simpson and Al Cowlings skipped class to shoot dice when McBride caught them. Simpson figured McBride, who was in line to be the varsity head coach, would give them some light punishment so they could play and win the JV title, which would McBride get the promotion.

Instead, McBride took them to the dean's office, and Simpson presumably didn't play in the title game. Simpson recalled McBride telling him that we all have to live by a certain set of rules in life, and if you're going to be successful, you have to accept responsibility for your actions.

Simpson said those words grew on him over the years. He realized that McBride was a moral man, and that has got to mean something.

"And I guess that is when I began to realize that it really, really is secondary if you win or lose," Simpson told the Canton crowd that day. "It's how you play the game in life and on the field that really matters."