On the eve of his coronation -- a 220-yard, four-touchdown performance to push the 49ers to the Super Bowl -- Raheem Mostert hit a bump in the road. In the dark, in a rush, and on his way to an event, Mostert drove over something; he still doesn't know what exactly. He also didn't know what he'd find out when the sun eventually came up and shined a light on the problem; at the time, some might've called it an omen or a harbinger. He sped along without bothering to check for damage. He went to the event. He drove home after. It wasn't until the morning that he realized he had a flat. The entire tire would need replacing, a problem almost every driver confronts at some point, but not the kind of problem one wants to deal with the day before the NFC Championship Game.

"It was one of those wild moments," Mostert tells CBS Sports. "I couldn't believe it was happening."

Like most professional athletes, Mostert maintains a game-day routine. For one, he usually drives to the stadium. The flat tire threw off the beginning of that routine. He took the team shuttle instead.

Once he arrived at Levi's Stadium, as the kickoff to the biggest game of his career approached, he fell back into the comfort of his routine. He doesn't take the field prior to kickoff anymore, a habit he borrowed from teammate Richard Sherman this season. Now, he stays indoors, inside the locker room, where he can stretch and review his playbook, but more importantly, collect his thoughts -- sometimes relaxing in the hot tub -- so that when he does take the field, he's ready.

"When I take in the field," Mostert says, "I want to take in the full experience."

But before that moment comes, Mostert does something that's been part of his routine ever since the beginning of a journey that really started when the Eagles made the decision to cut him, an undrafted rookie who led the league in yards from scrimmage in his first preseason, on the eve of the 2015 season. He pulls out his iPhone, opens up the Notes app, and reads the list of six teams and the corresponding dates when those six teams each decided to cut him.

He goes through it "thoroughly;" it takes 10-15 minutes. Call it a ritual or motivation. He calls it "meditation."

"It's more like a meditation deal for me," he says. "I just collect my thoughts and just think about the journey I've gone on and where I'm at that moment."

If his list reminds you of Arya Stark's, you're not alone in thinking that. He thinks it too.

"Oh yeah. Oh yeah," Mostert says. "I could definitely relate to her. She memorized everybody. That's actually really good, because I definitely see myself like Arya Stark."

Arya's list was about bringing justice to those who wronged her and her family, but also about vengeance in the form of death. Mostert's list isn't as much about vengeance as it is about appreciation.

"It's their loss. I'm not too bitter about it. I've moved on," Mostert says. "It just makes me appreciate what I went though."

The document isn't just a list. It's also a reminder of why -- why he plays football. Below the list, he's written out his whys. The whys are important. Without the whys, Mostert might've left the game of football behind after one of the six teams deemed him not worthy of a roster spot.

"I've been playing football since I was seven," Mostert says. "I've never really missed a whole year of ball unless it was due to an injury, but I'd come back and play. I never missed a full complete year of football. I've always played. So for me, it was like, hey, if you love this sport you'll do anything. And I do, so I'm just going to stick with what I know and just try to elevate my game as best as possible."

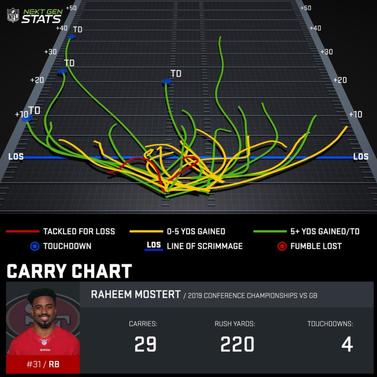

When Mostert took the field against the Packers, underneath the lights and a sea of screaming red and gold fanatics, he had no way of knowing what was about to happen. He couldn't have known the 49ers would beat the Packers by running the ball 42 times for 285 yards and four touchdowns. He couldn't have known Kyle Shanahan would call for a run on third-and-8 and that he'd turn that carry into a 36-yard touchdown that gave the 49ers a lead they wouldn't relinquish. He couldn't have known starting running back Tevin Coleman, who signed a two-year, $8.5 million deal with the 49ers this past offseason, would leave in the second quarter with a game-ending injury, placing an even bigger load on Mostert. He couldn't have known that he alone would account for 29 of those 42 carries, 220 of those 285 yards, and all four of those touchdowns.

But those things did happen. Mostert did become the first player in NFL history to record at least 200 rushing yards and at least four rushing touchdowns in a single playoff game. Only Eric Dickerson (in 1986) has registered more rushing yards (248) in a postseason game. Behind a wall of blockers in Shanahan's zone-blocking scheme, he was so electric that 49ers quarterback Jimmy Garoppolo attempted only eight passes over the course of the game.

He powered the 49ers to the Super Bowl, taking full advantage of the openings with his game-breaking speed.

🏄The NFC Championship turned into a Raheem Mostert clinic 🏄@RMos_8Ball

— NFL (@NFL) January 20, 2020

🚨 220 rushing yards on 29 carries

🚨 4 rushing TD

🚨 Single postseason game rushing record set @49ers | #GoNiners pic.twitter.com/4GhTrWk5L9

Normally, an average like 7.6 yards per attempt is associated with a quarterback throwing the ball, not a running back running the ball. It's more than what Packers quarterback Aaron Rodgers averaged as a passer during the 2019 season.

Mostert's carry chart from his historic night looks like a quarterback's passing chart.

"Still surreal," Mostert said after the game. "I just -- I can't believe that I'm in this position right now and I did the things I did tonight."

The path to get to that position was anything but direct. In that way, Mostert has more than one thing in common with Arya, a nomad who, in the span of eight seasons, wanders from Winterfell to King's Landing to Harrenhal to the Twins to the Eyrie to Braavos to the Twins again and eventually, Winterfell and King's Landing to complete a circle. After a four-year college career at Purdue that included 136 carries, 759 rushing yards, and six touchdown runs in addition to a role as a kick returner, Mostert went undrafted and then proceeded to get cut by six teams in a span of 14 months.

At a certain point, Mostert stopped feeling the weight of each cut.

"I would say, truthfully, I got immune to being cut," Mostert says.

49ers faithful don't have many -- if any -- good memories of the short-lived Chip Kelly era. The 49ers posted a 2-14 record in Kelly's lone season, a season that saw Blaine Gabbert start five games for a franchise that once transitioned away from the Joe Montana era to the Steve Young era. But Kelly, now UCLA's coach, deserves a portion of the credit for what transpired during Sunday's NFC title game. He's the reason why Mostert is with the 49ers, and he played a role in Mostert's evolution.

Kelly was the Eagles' coach when they signed Mostert as an undrafted free agent in May 2015.

"It was like the biggest moment of my life," Mostert says. "Not just the money aspect, but the fact that I was able to get into the league and have the opportunity to showcase my talents -- what I can do -- since I wasn't necessarily used like that at Purdue."

Mostert didn't go to Philadelphia because it was his only choice. He picked Philadelphia out of a list of somewhere around nine suitors -- one of which was the Chiefs, he says -- because he was attracted to Kelly's fast-paced offense. Initially, it looked like he made the right decision. In four preseason games, he racked up 351 yards from scrimmage in Kelly's system, which was a perfect fit for Mostert's explosive set of skills.

But the Eagles ended up making Mostert their final roster cut on the eve of the 2015 season. He was "shocked."

"I was the last cut. Man, that was the hardest part, because I put so much out there. I did so much even on special teams," Mostert says. "I felt like I did quite a bit to contribute, to showcase my talent, to showcase ... that I'm capable of playing in the league."

Mostert stuck with it, knowing his contributions on special teams could make him valuable to a team. He embraced his value on an often overlooked portion of the game.

"His ability to really wrap himself around special teams is what has allowed him to stay in the league this long so he could develop as a running back," Kelly said, per the San Francisco Chronicle. "I'm not sure if he wasn't such a good special-teams player if he'd have the chance to develop into the type of player that he is now.

"And there's not a lot of guys that are willing to do that. I think that's kind of the hidden story. He's one of the best gunners in the NFL. But there's a bunch of guys that don't want to do that: 'Nah, I'm a running back. I'm not a special-teams guy.' Where Raheem's mind-set was like, 'I'll do whatever it takes.'"

Seven months ago, his wife Devon gave birth to their son. They named him Gunnar.

A year after the Eagles cut Mostert, the Bears became the sixth team to cut him in November 2016. Mostert landed with the 49ers, where Kelly was attempting to revive a once-great franchise with his brand of offense that once took Oregon to the heights of college football.

"He kept telling me, 'You keep doing what you're doing, you're going to get bumped up and eventually you're going to be playing,'" Mostert says. "I got bumped up to the 53-man roster and never looked back."

Mostert was officially signed on Nov. 28, 2016. On Dec. 31, he was activated from the practice squad. The next day, he made his debut with the 49ers in their season finale, carrying the ball once for six yards and garnering a few returns. Later that day, Kelly, along with general manager Trent Baalke, got fired.

"He helped me evolve into a person that went through all that, had to go through many different circumstances, but made a full circle," Mostert says. "He believed in me. He gave me the opportunity."

Shanahan and John Lynch were brought in to replace Kelly and Baalke. With Shanahan came a running scheme that, under his father Mike in Denver, turned a sixth-round pick in Terrell Davis into a 2,000-yard rusher, an MVP, a two-time Super Bowl champion, a Super Bowl MVP, and a Hall of Famer.

Mostert's rise was gradual. In 2017, he appeared in 11 games, returning five kickoffs, making eight tackles on special teams, and collecting six carries for 30 yards. In 2018, Mostert appeared in nine games, registering six tackles and amassing 34 rushing attempts, which he turned into 261 yards and a touchdown. In the offseason, Mostert signed a three-year deal worth an average of $2.9 million per season. But it wasn't until 2019 that he carved out a meaningful role on offense, racking up 137 carries and 14 receptions for 952 yards and 10 touchdowns as the 49ers earned the top seed in the NFC.

In his playoff debut, a 27-10 win over the Vikings, Mostert played a meaningful role in the win, carrying the ball 12 times for 58 yards and recovering a muffed punt. And then came the explosion. With Mike watching from above and Kyle calling the shots, Mostert exploded, taking full advantage of the holes his teammates provided him. According to ESPN, 142 of his 220 yards came before contact.

That's partly due to the scheme and the blocking in front of him, but also because of Mostert's acceleration and ability to make the right reads.

How does Mostert get past both of them untouched?! pic.twitter.com/nQT6E74CLj

— Marcus Thompson (@ThompsonScribe) January 19, 2020

"This scheme that we run -- the outside zone and inside zone -- it's been working for years," Mostert said after the game. "Even back when Mike Shanahan was the head coach in Denver and even in Washington. The philosophy still transpires into what we run today. You have to have vision in order to read the holes and read the gaps, and I worked on it."

It was a performance years in the making, not just because of the motivation he drew from the six teams that cut him, but because by the time the NFC Championship Game rolled around, Mostert had spent three full seasons in Shanahan's system. For a returner, gunner and running back who mostly took the field for gadget plays, the transition to Shanahan's system took time.

"I'm usually more of the guy that's running the jet sweeps and all that type of stuff," Mostert says. "Me having to transition from doing all of those things in college and even some of it in the league to running a gap scheme, it took a little bit of time to understand. But once you get to it, man, you really understand concepts and you really understand how the blocking techniques work and everything like that. It makes it a lot easier as you transition. ...

"I've been in the offense now for what, three years? Like I said, it's one of things where I'm still feeling out different reads and stuff like that and different schemes. Every game is different. There's not really the same run every game, even though it looks like to the normal eye of a fan or someone on the outside, but it is changing week in and week out."

Mostert can't help but lament "a couple bad reads that I wish I could've made up for."

"I'm still learning to this day, truthfully," he says. "There's always something in this offense that he's throwing out there for us."

With two weeks between the NFC Championship Game and the Super Bowl, Shanahan will have enough time to come up with new wrinkles to exploit an improved, but still beatable Chiefs defense. He'll have time to throw everything at the Chiefs.

The Chiefs defense's weakness is stopping the run. The best way to beat the Chiefs is to keep Patrick Mahomes off the field. So, it's not unreasonable to expect a busy night for the 49ers' backfield.

Mostert called getting signed by the Eagles the "biggest moment" of his life. Sunday might just find a way to top it.

It's anywhere between 6:30 and 7 a.m, and Mostert and a group of friends are already in the water riding surfboards. It's early, but the best waves come early. Mostert is 14. He's waiting to catch a wave when he notices a fin protruding from the surface. He starts to panic. But his friends remind him that freaking out is exactly what you're not supposed to do when you encounter a shark. He puts his feet up on his board. He waits. He sits like that for a good minute until he thinks the coast is clear. Only then does he leave.

"I got out of the water," Mostert says. "I was done for the day."

Done for the day, but not forever. Eventually, he got back in the water and back on his surfboard.

Shark sightings aren't much of a rarity at New Smyrna Beach, Florida, where Mostert grew up. It's known as the shark attack capital of the world. According to National Geographic, it's estimated that if you've swam there, you've been within 10 feet of a shark.

It's also 250 miles north of Miami, the site of Super Bowl LIV. In a way, Sunday's game will be a bit of a homecoming.

Mostert wasn't a Dolphins fan growing up, but he was a Ricky Williams fan. He remembers everything about the day he went to watch Williams and the Dolphins beat the Patriots as a child in 2002. It's the first memory he can think of.

"I remember I tried Tabasco sauce for the first time at a tailgate," he says. "And it was actually pretty good."

Seventeen-and-a-half years later, Mostert is heading back to Miami, this time to play against the Chiefs in the Super Bowl. Coleman's status remains an unknown. So does Shanahan's gameplan. What is known is that the 49ers offense will be asked to score a bundle of points to keep pace with the world's greatest quarterback and a Chiefs team that averaged 28.2 points per game in the regular season before hanging 51 on the Texans and 35 on the Titans to earn the right to meet the 49ers in the Super Bowl. The Chiefs' defense, while vastly improved from a year ago and earlier this season, remains stronger against the pass (sixth by DVOA) than the run (29th).

There's no way to know how Sunday will unfold, just like there was no way to know Mostert would do what he did against the Packers, but barring an unforeseen bump in the road, Mostert will undoubtedly play a role after his history-making performance to push the 49ers to the Super Bowl -- at least a bigger role than anyone, certainly not the six teams that cut him, ever could've anticipated.

Since the NFC Championship Game, Mostert has been hounded with media requests. Between that and social media blowing up, he says that's how his life has changed over the past few days. In that sense, not much has really changed. The stage has gotten bigger, but his mindset remains the same.

He's still trying to master Shanahan's offense. He's still focused on making the right reads. He's still playing football for the same whys, the whys that enabled him to get to this point. He still spent the Tuesday after his coronation replacing a flat tire.