Marco Estrada and next generation of pitchers put a new spin on pitching

Up is the new down for young pitchers around baseball. Higher arm slots and "spin rate" are changing the way young pitchers approach pitching.

When describing the art of pitching, Hall of Famer Warren Spahn would often offer up a pithy quote: "Hitting is timing," he would say. "Pitching is upsetting timing."

Pitchers have a few techniques they can use to upset that timing. The most obvious one is to change speeds, mixing in changeups and slower breaking balls with hard fastballs. Another big one is to change the hitter's eye level. If a hitter expects a pitch to come in high, throw low; if he's looking low, throw high.

It's that last method that's gaining traction among a small but impressive group of improving pitchers. While baseball's pitching mantra for decades has been to keep the ball down, these guys are peppering the top of the strike zone with fastballs...and thriving by doing so.

No pitcher has taken that approach to heart more than Marco Estrada. When the Blue Jays traded Adam Lind to acquire Estrada after the 2014 season, you could have fairly asked what the hell then-GM Alex Anthopoulos and company were smoking. Estrada was coming off a season in which he posted a 4.36 ERA, while allowing 1.7 home runs per nine innings -- by far the most gopheriffic line in the majors. Bringing Estrada to homer-happy Rogers Centre and having him face stiff AL East competition looked like a spectacularly bad idea.

Since then, the veteran right-hander has fired 205 2/3 innings, posting a strong 3.11 ERA and allowing a far more manageable 1.1 homers per nine frames.

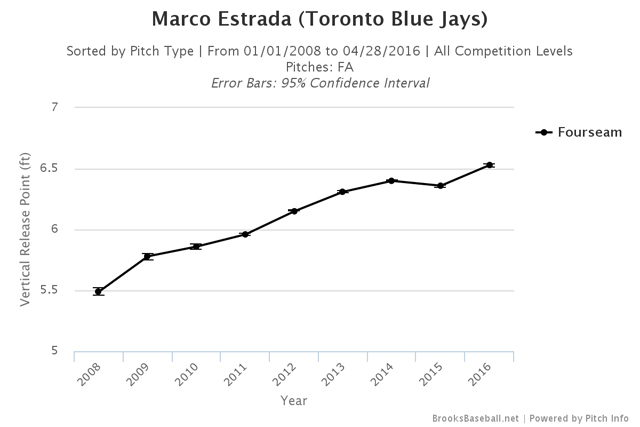

Estrada's transition from meatball delivery man to highly effective starter began with a simple change: He started throwing from a higher arm angle. The chart below shows how Estrada has progressively raised his arm angle over the year, from a near-three-quarter delivery when he broke in as a reliever with the Nationals to throwing at much more of an over-the-top angle now. His release point has climbed by more than a foot over that span:

We can see this in a different way by comparing screenshots of Estrada's arm angles over the years. Compare his release point in this 2011 Matt Kemp at-bat…

|

...to his release point in last week's matchup with Mark Trumbo...

|

...and you can spot that higher current arm angle.

We can identify a few reasons for this change in approach. Consider how the strike zone has evolved over the past few years. As excellent Hardball Times analyst Jon Roegele chronicled in a series of articles last year, the strike zone grew significantly from 2009 through 2015, tracking almost exactly with the length of Estrada's major league career. And it did so in a downward direction, with umpires increasingly calling strikes on pitches at or even below the knees.

Though that downward expansion of the zone did level off last year, the result was that hitters started gearing up for lower pitches too, thus showing the same ability to adjust that Spahn preached with pitchers. Go back 10 or 15 years, and the belt-high pitch would be the one you'd expect to get crushed. Go back to Bob Gibson's days, and hitters' sweet spots were often closer to the navel, given that pitches up to the letters would often get called as strikes. As Estrada recently explained to Fangraphs writer David Laurila, hitters have adjusted to the current lower strike zone by establishing a new sweet spot.

"You can't go thigh to belt," Estrada said in that interview. "That's the danger zone. You have to go above the bellybutton to the letters. That's the safe zone. If you go above that, no one is ever going to swing."

To connect the dots from Estrada's elevated arm angle to his newfound desire to pound the high end of the strike zone, we need a very basic physics lesson. Alan Nathan, professor emeritus of physics at the University of Illinois, has explored the intersection of baseball and physics in multiple places, from his own website to well known analytical sites such as Baseball Prospectus. In his work, he delves into how pitches can spin in different ways based on what's thrown (fastball vs. curveball) and what arm angle those pitches are released from.

For instance, White Sox ace Chris Sale throws from a lower arm angle than many starters; follow the plot points in this chart and you can see that the highest release point of his career pretty much exactly matches the lowest release point of Estrada's career. So when Sale releases the ball, the net effect -- other than eliciting sheer terror from hitters -- is that he's slinging the ball, thus generating a ton of sidespin. As a result, Sale generates a staggering amount of horizontal movement on his pitches... more than any other pitcher in baseball this season, when looking at four-seam fastballs.

On the other hand, by changing his arm angle to a more upright position, Estrada has become adept at generating a different kind of spin. Scouts will sometimes talk about a particularly nasty fastball as "rising." While it's not actually possible for a fastball to rise, it is possible for it to appear to be doing so. PITCHf/x measurements refer to this kind of action as vertical movement. The pitcher with more vertical movement on his fastball than anyone else in baseball so far this year? Our pal Marco Estrada. (To get that ranking within that Baseball Prospectus link, select 2016 in the "Years" drop-down, then "100 Pitches Min," then sort by "V Mov." To see Sale's ranking for horizontal movement, do the same thing, but ending with "H Mov.")

Firing fastballs up in the zone is both a counterpunch against the prevailing "keep the ball down" convention wisdom, and also a potential trend that could bear watching. Multiple Rays pitchers, including dynamic young left-hander Drew Smyly, have put up encouraging numbers by peppering the top of the zone with fastballs. Collin McHugh was a journeyman pitcher whose career appeared headed nowhere when the Astros nabbed him for the tiny price of a waiver claim in December 2013. Turned out that McHugh graded highly by spin rate. Finally given a clear shot at a full-time rotation spot in 2015, McHugh was one of the league's biggest pleasant surprises, and one of the biggest reasons Houston stormed to the playoffs, after years of futility. (He's struggled in his first five starts this season.)

Elsewhere, veteran Red Sox righty Koji Uehara's fastball lives in the high-80s at this advanced stage of his career. But it's still an often effective pitch, both because he complements his heater with a dive-bombing splitter, and because he generates so much spin on that fastball. As for Estrada, he uses a playbook similar to Uehara's, putting copious spin on his sub-90 mph fastballs, and complementing those offerings with a slower pitch that sinks. In Estrada's case, that's a changeup that has held opponents to a batting average below .200 every year since 2013.

It's very tough to find leaderboards for spin rate the way we might for pitcher wins or earned run average. MLB.com releases a few figures in dribs and drabs via its Statcast system, but most of that data remains available to private eyes only -- i.e. the eyes of number crunchers and executives in major league front offices. You can find some useful spin data on robust baseball analysis sites like Brooks Baseball, though the raw figures shown there don't adjust for park factors, and thus don't account for oddly distorted spin measurement figures at a handful of ballparks.

What we can do for now is work with what we've got. We can peruse the leaderboards for measures such as horizontal and vertical movement. And at the risk of selection bias, we can watch with our eyes, see Smyly blow a fastball by a helpless batter or Estrada induce a lazy flyout with the same pitch, and crack a knowing grin.