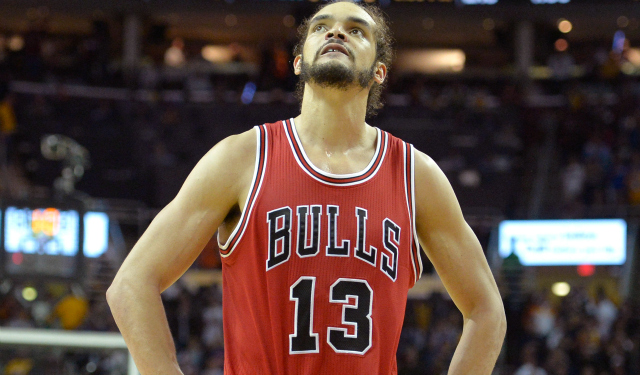

Joakim Noah's California summer could make Bulls a contender

Joakim Noah changed everything up this summer, and this could mean Chicago is a contender.

At the end of the summer, Joakim Noah walked into Murchison Gymnasium at Westmont College, a small, Christian liberal arts school in Montecito, Calif. The Chicago Bulls center was there to play pickup basketball. On the opposing team was Al Jefferson of the Charlotte Hornets. The rest of the participants represented the Westmont Warriors, last year’s NAIA runner-up.

The Westmont players weren’t awed by Noah. They took the games seriously and they went at him. There was a ton of ball movement, cutting and speed. Noah acted like he was just one of the guys.

Thanks to a new and challenging offseason routine, the version of Noah at Westmont moved nothing like the one who had knee trouble and saw just about all of his numbers drop last season. This version, the one Chicago head coach Fred Holberg said looked “awesome” in training camp, is quicker, jumps higher and has more lean muscle.

Still, when Alex Perris, Noah’s longtime trainer and best friend since high school, shows people footage of these games, they all wonder the same thing: Why in the world was the 2014 Defensive Player of the Year sharing the court with these guys?

When a group of NBA players showed up late for their training session at Peak Performance Project (P3) in Santa Barbara, they had to explain that they’d gotten sidetracked — driving by the beach at about 7:30 a.m., they saw Noah’s big head of hair coming out of the water. They decided to stop and say hi. For Noah, a dip in the Pacific Ocean was the standard way to start to the day. Three or four mornings a week, he’d be on FaceTime before that with his yoga instructor. He liked to get a session in, then eat breakfast.

Five days a week, Noah went to P3. There, he followed a precise training program based on enormous amounts of data in an effort to get healthy and reduce his risk of injury. In the afternoon, he worked out with former Los Angeles Lakers guard Mike Penberthy, who now specializes in player development. Noah ate dinner and went to bed early so he could recover and repeat the process.

Dr. Marcus Elliott, the founder of P3, sold Perris on his plan in January. Perris and Matt Rosenberg, who also grew up with Noah and now works for his agency, toured Santa Barbara and the facility. When Noah saw the information they took home, he bought in right away. It didn’t hurt that his ex-teammate, Kyle Korver, had been telling him about the place for years and played in his first All-Star Game a month before turning 34.

“They showed us the testing and we just thought that the technology and where they were was way ahead of anything we’ve ever seen,” Perris said. “With the importance of his offseason and coming back from his injury and the Bulls’ prospects of winning, we were just like, ‘Why take any chances? Let’s do this, let’s go there and commit to it.’ And we did.”

On the first day, Noah did all of P3’s standard testing with motion-capture technology so a personalized program could be designed. By the end of the summer, his performance metrics were all completely different.

“Everything improved, physically,” Elliott said. “I mean literally everything. He had a handful of biomechanical things he did that didn’t serve him that we worried about. Some of them were compensation patterns from old injuries and some of them were just the way he moved. He did some things that were hard on his body. And all those things improved. His risk of injury is much, much less than what it was before.”

In a couple of months, Noah made more progress at P3 than almost anyone. When he moved laterally, at first he wasn’t stable enough in his trunk, which meant he flexed it and lost energy. On exit testing, his trunk flexion was down from 21.6 degrees, a bad outlier, to 12.1 degrees, much better than an average NBA big man. His drop jump — a vertical jump off a box — went up 4.5 inches. With plyometrics, he learned how to be much more efficient when he landed, which took pressure off his knees and allowed him to jump not just higher, but faster.

As Noah saw the results, his enthusiasm was evident. His one-on-one basketball workouts got extremely technical, but Penberthy started with simple conversation, trying to get to know him better. Penberthy thought Noah was searching for excitement after a difficult season, and his objective, beyond trying to teach him some skills to help him in the Bulls’ new offense, was to help him find it after a difficult season.

“The goal was just to get him to fall in love with the game again,” Penberthy said. “I think the hard part was just the pressure of trying to win and that whole situation with everybody last year in Chicago just really took its toll on him. I just wanted him to enjoy playing again.”

Noah had new life almost immediately after getting in the gym. He had no problem with doing 45 minutes to an hour of non-stop activity in order to feel the same adrenaline as he would in a game. Penberthy called him the hardest-working guy he’s ever seen, and his attitude was as impressive as anything.

“When I deal with superstars, and I’ve dealt with a lot of them, it’s rare to find a guy who comes in ready to learn,” Penberthy said. “Most guys are saying, ‘What’s this little white guy going to show me? What does he really have?’ And then once you build that trust, then I can unleash everything on him. But you’re trying to find connecting points. When he walked in the door, he just said, ‘Coach!’ Which was basically him saying, ‘Show me what you got.’ The walls were kind of brought down.”

Noah listened and made little changes. “We gotta adjust your hook angle,” Penberthy told him. “We gotta get you a floater, a little bit of a runner because of the depth of your pick-and-rolls. Your dribble spin move can be out of control, we gotta slow you down.” He and Penberthy practiced footwork and decision-making — when he rolled to the basket, he’d attack when he caught the ball low, kick out when he caught it high. If he misses a few easy-looking shots in the beginning of the season, it’ll probably be because he’s getting used to having the ball roll off his fingers in a more traditional way.

The 30-year-old Noah didn’t pay much attention to all the stories saying he looked like a shell of himself, his body was betraying him and he couldn’t complement Pau Gasol. He learned long ago that there’s enough pressure on him without letting others add to it. Still, Perris described 2014-15 as “a year of frustration,” as Noah was always feeling the effects of the offseason surgery he had on his left knee.

Noah has long been Chicago’s spiritual leader, known for his hustle plays and exuberance as much as his triple-doubles. He couldn’t be himself because of his lack of mobility, but still played in 67 games in the regular season and handled big minutes in the playoffs.

“I see him hurting, it makes me sad,” Perris said. “Just seeing him like that, it was so unusual. And it was hard. It was a difficult season and we stuck together and pulled through and he really fought through and I’m really happy he played as many games as he did last year. And I think he gave them everything he had.”

Perris said “everything was all mixed up” in terms of their regimen. He tried to keep everything as normal as he could, but they couldn’t get their regular weightlifting sessions in because Noah needed that time for recovery. Now things are back to normal, and both P3 and Penberthy will continue to be a part of his training.

Elliott sees “exact parallels” to Korver, who started going to P3 in 2008 while dealing with several injuries. Rather than getting less athletic in his 30s, Korver ended up being able to do things he couldn’t when he came into the league. Elliott is confident Noah will keep improving and produce like he used to. That’s saying something, considering he finished fourth in MVP a couple of seasons ago. If he reaches that level, the Bulls are contenders. If he doesn't, they're probably not. While Hoiberg will equip them with a more modern offense, Jimmy Butler should continue ascending and Derrick Rose is trying to stay on the court, perhaps nobody can transform this team like a full-strength Noah. It is hard to overstate what he can give Chicago as a defender and facilitator.

“I don’t see any reason why, over these next couple years, he shouldn’t be in as good of physical shape as he’s ever been if he continues with the approach that he had this summer,” Elliott said. “Physically, everything has improved. He’s going to be a whole lot better than what he was last year. If he wasn’t, it would just be bizarre. It just wouldn’t make any sense.”

Everybody who saw what he was doing at the end of the summer agreed: Noah is going to make people forget about the guy who had trouble covering ground on defense. After a couple of months of focused, targeted work, it was obvious.

“He was a totally different player,” Penberthy said. “He was quick, he was explosive and he was in above the rim. It was just a different guy. He looked young. And he wasn’t just worried about his knee. Like last year, he just kind of lumbered and struggled in a lot of those areas. He was bouncy again.”

Westmont’s players had a chance to witness that up close, and Penberthy, one of the few to make it from the NAIA to the NBA, encouraged Noah to play there. Far away from expectations and far removed from playing hurt, he tried out everything he’d been practicing. No one worried about what anyone was saying about Noah heading into a contract season, and no one played selfishly. He loved it.

“There’s nothing better than just enjoying basketball for being basketball,” Penberthy said. “There’s no motive there. It’s just, 'let’s hoop.’”

Throughout his tenure in Chicago, he has always been at his best with a clear mind and healthy body. That’s why he was sharing the court with those guys.