The inside story: How the Magic let the Lakers steal Shaquille O'Neal

Our Joel Corry was in the meetings, and he still can't believe Orlando let it happen

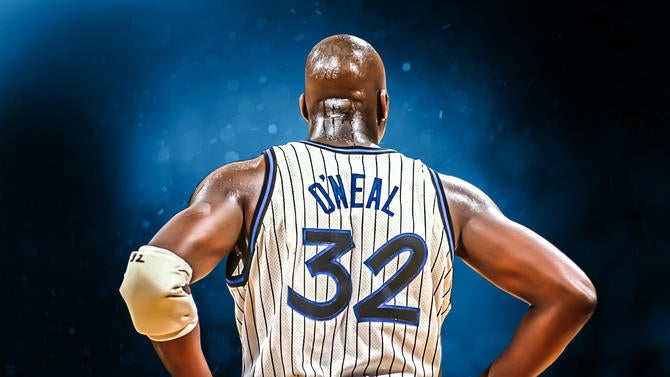

Twenty years ago this month, Shaquille O'Neal, 24 years old and already poised to become one of the most dominant forces in NBA history, left the Orlando Magic to join the Los Angeles Lakers. Looking back, it was perhaps the most significant free agent signing ever. In any sport. Never before, and at no time since, has a single free agent's decision so definitely destroyed one potential dynasty while, at once, birthing another, and even that fails to capture the full impact of this move. The day Shaq went to L.A., the entire NBA landscape shifted in a way that is still being felt today.

And I still can't believe it happened.

Back in 1996, I was working as a consultant with Shaq's agent, Leonard Armato, who was my former boss before I went on my own to help form another agency. This consultant position gave me a front-row seat for probably the most botched negotiation on the part of an NBA team that I can recall in my 16-year career in the athlete representation business. There is no way Orlando should've lost O'Neal. Everything was stacked in its favor to keep him.

Well, everything except for one very specific, very unexpected change to the Collective Bargaining Agreement, which was all the opening the Lakers needed to ultimately lure Shaq by way of probably the single-most brilliant salary-cutting measure the NBA has ever seen. We'll get to that.

For now, let's focus on the Magic, because this was their negotiation to lose, and man did they lose in a big way. I was there through the whole thing. In the meetings. On the calls. I still have many of my files. And I still shake my head when I look at them.

Magic drop the ball early

Initially, almost all of our internal discussions focused on Shaq staying with Orlando. As mentioned, they simply had more to offer Shaq than anyone else, not just for their ability to offer him the keys to a budding dynasty with a potential Hall-of-Fame wingman in Penny Hardaway, but more specifically, and perhaps more importantly, the fact that they could offer him the most money.

In 1996, there was no maximum salary provision in the CBA. There was a salary cap, $24.3 million to be exact, but no max salary and no luxury tax penalty (both were products of the 1998 lockout). This is important. This meant that Orlando -- which owned Shaq's Bird rights and could thus exceed the cap to re-sign its own player, while everyone else had to get him under the cap which in many cases meant a full roster gutting -- could've thrown a blank check at Shaq (and not even incurred the luxury tax they would today) and, I believe, ended the negotiation before it started.

But they didn't do that. Instead, they lowballed him. Almost offensively so.

There are some aspects of Shaq's free agency that I remember like they happened yesterday, and that initial offer is one of them -- $54 million over four years with none of the yearly salaries specified, a far cry from the seven-year, $105 million deals Alonzo Mourning and Juwan Howard, both appreciably inferior players, had just received from the Miami Heat and Washington Bullets, respectively.

But that wasn't even the worst part. OK, fine, so the Magic offered $13.5 million per year with no opt-out and Shaq wanted something closer to $20 million per year with an opt-out after year three. It's a low offer, but not the first time two sides have been far apart in initial negotiations. The more baffling part of the call, and I'll never forget this, was that the Magic, I guess in an attempt to create some kind of leverage, actually criticized O'Neal's rebounding and defense.

Are you kidding me?

When you have a player of Shaq's caliber, a guy who in his first four years in the league had already won Rookie of the Year and a scoring title, been named to the All-NBA team three times, been a runner-up for league MVP and led Orlando to the Finals after knocking off Michael Jordan, not to mention made a habit of doing things like this ...

Shaq Breaking The Backboard Vs New Jersey Nets #ShaquilleONealhttps://t.co/Hm3pscLxt6

- Gustavo Vega (@iamvega1982) April 15, 2016

... you tell that guy he's the greatest thing since sliced bread. You bend over backwards to get a deal done with him. Instead, the Magic decided it was a good time to criticize major parts of Shaq's game?

Never mind that Shaq averaged more rebounds per game during his four years with Orlando (12.5) than he did in his eight years with the Lakers (11.8). That's not the point. It's the principle. The respect factor. Can you imagine the Thunder going into their meeting with Kevin Durant and saying, "Yeah, Kevin, you're a great scorer and all, but about that ball-handling and defense ..."

That's nuts. But that was the tone Orlando set for this negotiation. The Magic didn't seem to appreciate that Shaq was a franchise-altering talent, even though he had already completely altered theirs. The 1996 free-agent class was star-studded -- future Hall of Famers Jordan, Mourning, Dikembe Mutombo, Reggie Miller, Gary Payton and Dennis Rodman were on the open market -- yet it was O'Neal who was considered the crown jewel.

At that time, the prevailing championship formula in the NBA was that if you didn't have Jordan, you needed a dominant big man, and O'Neal was considered a modern-day Wilt Chamberlain who hadn't even reached his potential yet. The Magic had him right in their hands, the centerpiece of a budding powerhouse, and they took him for granted out of the gate. Lowballed him. Questioned his game.

In a sense, Orlando positioned itself as an antagonist to Shaq rather than an organization that was entirely in his corner, even saying on that initial call that they needed to maintain financial flexibility for Penny Hardaway's free agency a couple of years down the road, signaling to our representation team that Shaq wasn't the full priority we expected him to be.

It was about this time that we really started to consider alternatives as something other than backup plans. Finding these potential Shaq suitors and seeking out CBA loopholes to play to O'Neal's financial advantage were my primary responsibilities.

The idea was this: Identify the teams that could get to at least $9 million under the cap without gutting the roster in order to offer a seven-year, $100 million contract voidable after three years, when Shaq would have Bird rights with these teams and could thus opt out to take advantage of his presumably increasing value. Also, if he left Orlando, his preference was to go to a big market. There weren't many teams that fit all these requirements. This is the list we came up with:

- NEW YORK KNICKS: This was a longshot from the start, as it was contingent on New York being able to trade Patrick Ewing. The Knicks also went after Jordan, who promptly re-signed with the Bulls on a one-year, $30 million deal. The market was there. But moving Ewing was never really an option. And when they signed free agent Allan Houston for $56 million over seven years, the cap situation just became unworkable. Nothing ever really materialized.

- DETROIT PISTONS: Detroit was attractive because of 1995 NBA co-Rookie of the Year Grant Hill, who had already earned All-NBA honors in his brief pro career. Allan Houston was also starting to emerge, and the thought of putting Shaq with a scorer like Hill and a shooter like Houston was attractive. But when Houston made his move to New York, this pie-in-the-sky scenario went with him. Plus, frankly, the Pistons never really showed much interest in making a deal for Shaq happen. Detroit was out.

- MIAMI HEAT: The Heat had the most roster flexibility and potentially the best cap situation of the bunch, but renouncing the rights to Mourning, who was also a free agent, to wipe out his cap hold of 150% of his 1995-96 salary was going to be a necessity. Mourning became a central barometer for all of our negotiations. Mourning had gone No. 2 in the 1992 draft, right behind O'Neal, and their careers had been linked ever since.

People casually put them in the same conversation as big men, but Mourning wasn't the player Shaq was. When Miami signed Mourning to the aforementioned seven-year, $105 million deal, not only did it end any chance of O'Neal going to the Heat, it also served as an easy benchmark contract for Shaq's personal market.

No way was O'Neal going to get a penny less than Mourning, and in fact, Armato was adamant that O'Neal get substantially more than Mourning for he did not see them as anything close to the same class of player.

- ATLANTA HAWKS: While Atlanta wasn't on our initial list, the Hawks quickly became a viable option when I, along with a colleague, took a call from current Los Angeles Dodgers CEO and President Stan Kasten about the Hawks' interest in Shaq. Kasten, who was president of both the Hawks and Atlanta Braves at that time, indicated that the merger between Hawks owner Ted Turner's broadcasting companies (CNN, etc.) and Time Warner would be able to generate significant ancillary income for Shaq.

On the basketball side, he viewed Shaq as the missing piece to a championship in Atlanta and was comfortable offering him a seven-year deal averaging somewhere between $10 and $15 million per year. He was not, however, interested in breaking up much of his team to do so.

This is kind of crazy to look back on, but in 1996, Kasten considered Mookie Blaylock and Christian Laettner to be the Hawks' foundational players. They weren't going anywhere. Two other players from a group consisting of Stacey Augmon, Alan Henderson, Grant Long and free agent Steve Smith also needed to be retained.

This was the snag. After running all the numbers, Smith, an All-Star caliber player, was probably the odd man out, and we didn't like the idea of losing Smith. Eventually, Atlanta, which had become a legitimate contingency option, fell completely out of consideration when it signed Dikembe Mutombo to a five-year, $50 million deal.

Shaq wasn't going to take less money that Alonzo Mourning got in 1996. Getty Images

So Orlando was dragging its feet. Most other options were falling off our list. Only one team remained a true threat to lure O'Neal away from the Magic. It would take a perfect storm of circumstances to pull it off, but a perfect storm was indeed brewing.

Here come Jerry West and the Lakers

The first move the Lakers made in an effort to position themselves for Shaq was arguably the most significant draft-day trade since the St. Louis Hawks sent the draft rights to Bill Russell to the Celtics. In a piece of cost-cutting brilliance, the Lakers sent veteran center and fan favorite Vlade Divac to the Charlotte Hornets in a move that not only netted them 18-year-old Kobe Bryant, but also the $3.3 million of extra cap space his rookie deal afforded them.

In hindsight, this has to be one of the biggest steals in NBA history. The Lakers had actually saved money by trading for a guy who will probably go down as one of the 10 best players in history.

In doing so, the Lakers had now become a real threat, maybe the biggest threat, to secure Shaq, who was clearly interested in joining such a storied franchise. The day after my talk with the Hawks, Armato briefed us on a sit-down meeting he had with the Lakers' Jerry West, who had formally offered Shaq $95.5 million over seven years with an option to terminate after three.

The Lakers had an interest in getting the deal done quickly so they could then re-sign Elden Campbell. Having Campbell's Bird rights meant the Lakers could go over the cap to sign him, but they couldn't do that for Shaq, so they needed to get Shaq under the cap first and then add Campbell's salary. Still, Armato rejected the initial offer of $95.5 million over seven. It was the best deal that was on the table, but still below Mourning's deal and thus not enough.

At this point, West said he was willing to trade George Lynch for a draft pick to be able to further sweeten Shaq's deal, and all the while, he was really pitching the Lakers as a franchise, stressing their history with dominant big men (George Mikan, Wilt and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar), their winning tradition and his own ability to build championship teams. With Eddie Jones, Cedric Ceballos, Nick Van Exel and Bryant on board, the Lakers were a promising young team that were coming off a 53-win season. L.A. was closing strong.

Magic still nickel and diming

At this point, the Magic were more or less doing what we just saw the Miami Heat do to Dwyane Wade this summer -- offering not what Shaq deserved, not what would be commensurate with his value to the franchise, but rather only reacting to what other teams were willing to pay.

At this point in his career, Wade is clearly not the player that Shaq was in 1996, but the way the negotiations were handled were very similar. The Heat's passive approach wound up costing them Wade. From our side, you could feel the same thing starting to happen to Orlando with Shaq.

After all, instead of immediately upping their offer after the Jordan, Howard and Mourning signings, it was only when the Lakers dealt Lynch and Anthony Peeler to the Vancouver (now Memphis) Grizzlies, thus freeing up even more cap space to pay Shaq, that the Magic revised their position. They presented Armato with two options: a four-year deal at $64 million, up from the original $54 million, or a seven-year deal at $109 million with an opt-out after year four rather than year three, which was Shaq's preference.

It was bewildering, to be honest. We were all scratching our heads to think that still, at this point, with its franchise player potentially slipping away, Orlando was haggling over an opt-out year. We had just seen the Bulls give their franchise player a one-year deal that was some $6 million more than the entire salary cap on its own. Shaq wasn't Michael Jordan, nobody was, but he was definitely perceived as the next great superstar. The way we saw it, after the Lakers made their offer, the Magic could've just jumped in and blown everyone out of the water, just as they could've done from the start. This thing would've been over.

But again, they didn't. They wouldn't go to $20 million per year over a longer deal. They were nitpicking the opt-out year. They were trying to effectively offer dummy money in the way of not-likely-to-be-earned incentives, such as Shaq, a historically horrible free throw shooter, shooting 60 percent from the line, which, incidentally, he only did one time in his NBA career. In essence, they were sealing their own fate with their stubbornness.

It was right about this time that the final nail got driven into the Magic's coffin.

The poll heard 'round Orlando

To be fair to the Magic, it's not like the kind of money Shaq was asking for was peanuts. At the time there were only two $100-million-plus contracts in the league, Howard and Mourning. The $20 million per year he sought from the Magic (he expected more from them because they had his Bird rights) represented more than 82 percent of the 1996 cap. That's a lot. By comparison, the Grizzlies' Mike Conley just got the largest total contract in NBA history at $153 million over five years, which works out to roughly 30 percent of the cap in year one.

Remember, too, that at the time there was sort of a prevailing sentiment among fans that players were being paid way too much money. There had been a brief lockout in 1995, souring some of the public relations, and there was definitely a disconnect between the common fan and superstars that has softened over time, to the point that nowadays I would say more people support the money these superstars are making, or at least are indifferent to it, because they know how much revenue they're producing. But in 1996, a hundred million bucks to play basketball had an outlandish ring to it.

Playing to that debate, the Orlando Sentinel conducted a poll asking whether Shaq was worth $115 million. At that time, you could've asked that question about any player in the NBA, probably including Jordan, and fans would've said no, and sure enough, over 90 percent of the some 5,000 people who responded didn't feel Shaq was worth the money.

The poll coincided with Dream Team II relocating to Orlando for final preparations before the Olympics, and Shaq was not happy. Not only did the team basically tell him he wasn't worth the money that lesser players were getting, now the fans were were telling him the same thing.

This is the human part of these negotiations that sometimes gets lost in all the big money talk. Athletes, just like regular people, want to feel valued. From the outset, the Magic had done virtually nothing to make Shaq feel that way. Meanwhile, the Lakers, thanks in large part to that unexpected CBA change I mentioned earlier, were more than ready to jump in and show Shaq the love and money he both desired and deserved.

A dynasty is born

The Lakers were indeed taking a risk by holding up the rest of their summer plans to wait on Shaq. One by one, their backup plans were signing elsewhere. Dale Davis was the Lakers' first option behind Shaq, but he re-upped with the Indiana Pacers for $43 million over seven years as he'd grown tired of waiting. Mutombo, another alternative, was no longer available. Chris Gatling went off the market on a five-year, $22 million deal with the Dallas Mavericks.

An inquiry was made by the Lakers about Dennis Rodman, who hadn't yet re-signed with the Bulls, but that never came to fruition. Other options being considered were Brian Williams (later known as Bison Dele) and two defensive-minded centers, Ervin Johnson, who wound up getting $18 million over seven years from the Nuggets, and Jim McIlvaine, who signed a seven-year, $33.7 million deal with the Seattle SuperSonics.

Fortunately for the Lakers, Plan A worked out.

As soon as the trade sending Lynch and Peeler to Vancouver went through, West immediately upped the Lakers' offer to $120 million over seven years with an opt-out after the third year. After hearing this, Orlando tried at the last minute to sweeten its offer with better cash flow, but they had lost whatever leverage they had to begin with, which wasn't as much as they apparently thought, certainly not after the rules of free agency had unexpectedly changed after O'Neal signed his seven-year, $39.9 million rookie contract in August of 1992.

See, prior to 1995, two completed contracts and a minimum of four years of service were required for a free agent to be deemed unrestricted, and thus be able to sign with any team he wanted without the incumbent team having the ability to match any offer. The CBA that resulted from the 1995 lockout, however, eliminated restricted free agency for the first and only time in the salary cap era.

After the 1998 work stoppage, the CBA returned to its original rules regarding free agency, but during this one three-year window, and only during this three-year window, every free agent was unrestricted.

In other words, had Shaq, with just four years and one completed contract under his belt, been a free agent in this year's class, or in 1994, or 1998, or 1999, or 2000, or at any other time in free agent history other than that one three-year window, the Magic would've had the ability to match L.A.'s offer of $120 million over seven, which, for all their missteps, they surely would have done.

But in 1996, they didn't have this luxury. If Shaq wanted to take the Lakers' deal, there was nothing Orlando could do about it. Armato personally went to Atlanta to discuss the offers with Shaq.

I wasn't a part of Armato's discussions with Shaq, but I was told that Orlando constantly reacting to the Lakers instead of being proactive, coupled with the resentment Shaq felt about the Sentinel's poll, had pushed him over the edge. In the end, Orlando's ability to frontload the contract and Florida not having a state income tax, while California's rate was sky high, took a backseat to how Orlando had handled the negotiations.

Shaq didn't want to leverage L.A.'s offer against the Magic again. He was ready to end the process and sign with the Lakers. A couple of days later, before the start of the Olympics, a press conference was held and the deal was announced. And the NBA has never been the same.

In the years since, I've tried to wrap my head around all the ripple effects of this deal, which are still being felt today. Think about all the things that change if Shaq stays in Orlando, which I'm still convinced he would have done -- considering what they were building with a still healthy Hardaway, Nick Anderson, Dennis Scott and a recently re-signed Horace Grant (5 years, $50 million) -- had the Magic not so blatantly dropped the ball.

For starters, the Lakers never become a dynasty without Shaq regardless of how much production they got from Kobe. Phil Jackson may never have gone to Los Angeles, where he won five more rings. After all, running the triangle offense with a dominant big man, something Jackson never had in Chicago, was a primary reason for him taking the Lakers job.

Kobe, for all his greatness, probably doesn't win five rings in his career. At least not with the Lakers. Who knows how long he would've even stayed in Los Angeles. His legacy might well have been built in another city. Perhaps he goes home to Philadelphia. Perhaps, then, Philly never has to start tanking, its "process" never even starts, the lottery order changes, guys end up going different places, and suddenly the league as we know it today has been flipped upside down.

That's just one scenario. There are a hundred more just like it.

Who knows, for instance, how great that Orlando team could've become. Sure, Penny's career wound up being derailed by injuries, but they would've still had a window to be great. Maybe they challenge the Bulls' supremacy in the East.

Chicago would've been most vulnerable in 1998 during its final championship run, provided Penny Hardaway's knees held up, and if Jordan is denied his second three-peat and ends his career with only five rings, perhaps he isn't so universally regarded as the greatest player ever but more on par with Magic Johnson.

Meanwhile, the San Antonio Spurs, who lost three playoff series to Shaq and the Lakers during the first half of the 2000s, would have had a much better chance of consecutive NBA Finals appearances with O'Neal in the Eastern Conference.

It's conceivable that the Spurs-Magic would have become the NBA's biggest rivalry with a healthy Penny. It's not hard to imagine them battling for league supremacy considering how weak the East was after Jordan's second retirement. The Magic breaking up because of a similar kind of tension that existed between Shaq and Kobe occurring between Shaq and Penny can't be dismissed either.

In the end, you can go down this rabbit hole as far as you want, and none of it is unreasonable. Shaq going to L.A. shifted the NBA landscape, both present and future, on a dime. Perhaps 20 years from now we'll recall Kevin Durant's recent decision to leave Oklahoma City in a similar fashion.

Durant's situation, really, is a good parallel for Shaq's situation in 1996. In OKC, Durant -- like Shaq in Orlando -- was on the cusp of a title. He had made one Finals appearance but came up short, attained huge levels of individual success, won scoring titles, became the face of a small-market franchise, and he had the superstar point guard as a wingman.

And he left it all for the glitzy California team where Jerry West said he could win championships.

Every time I see a big-name player leave his team in free agency, I think of Shaq in 1996. I think of the dynasty that became and the one that never got started. I think of Kobe and Phil and Jordan and Duncan, and that one window in the CBA that opened up the future -- or, I suppose, if you're Orlando, closed it.

I think about it all, and every single time, I think about the Magic telling Shaq he needed to rebound better and that stupid poll and quietly shake my head at how easily it could have all gone a different way.

Joel Corry is a former sports agent who helped found Premier Sports & Entertainment, a sports management firm that represents professional athletes and coaches. Prior to his tenure at Premier, Joel worked for Management Plus Enterprises, which represented Shaquille O'Neal, Hakeem Olajuwon and Ronnie Lott.

You can follow him on twitter: @corryjoel

You can email him at: jccorry@gmail.com.