NCAA tournament myth-busting: Have we really achieved parity?

Even though there is no clear-cut favorite this year, history shows the tournament might not be as wide-open as some might think.

Every year around this time, we hear the experts proclaim that parity has come to college basketball. In light of Gonzaga's ascension to No. 1 in the AP Top 25, it's fitting to ask whether the declaration is true for the tourney. Since 2006, a host of mid-major Cinderellas -- including George Mason, Butler and VCU -- have spoiled the party for the power conferences. But is this really a sustainable trend or a short-term aberration?

There are a couple of ways to answer the question:

- Assess whether more teams from mid-major and small conferences are getting into the dance in recent years.

- Determine whether they have improved their performance over time.

To make these assessments, I broke the 28-year tourney era (since the field was expanded to 64 teams) into four seven-year periods. Then I crunched the numbers for both power conferences (ACC, Big East, Big Ten, Big 12, Pac-12 and SEC) and everyone else. Here's what I discovered for the number of teams making the tourney:

- 1985-1991 - Power (201), Mid-Major/Small (247)

- 1992-1998 - Power (201), Mid-Major/Small (247)

- 1999-2005 - Power (217), Mid-Major/Small (231)

- 2006-2012 - Power (234), Mid-Major/Small (214)

The most recent seven-year period has actually seen the fewest number of mid-major and small conference teams in the tourney. Since 2006, only 47.8 percent of the tournament field has been comprised of nonpower conference teams. Over the first 14 years of the 64-team era, 55.1 percent of tourney teams came from smaller conferences. So, on the question of tourney inclusion, mid-majors and smalls are actually moving away from parity.

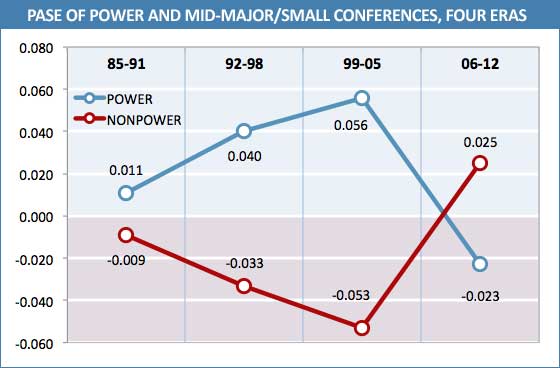

That doesn't say anything, however, about the performance of the fewer teams making the dance. I did a PASE analysis (that's "Performance Against Seed Expectations" if you haven't been following my blog) of the power and nonpower conferences for the same seven-year periods. This what I found:

Over the first three eras of the 64-team tourney, power conferences performed progressively better against seed expectations. It has only been in the last seven years that the trend has reversed and mid-major/smalls have been the overachievers. So an argument could be made that, while fewer nonpower teams are making the tourney, they're outperforming their power counterparts.

But let's not get carried away here. The +.025 PASE rate of nonpower teams works out to just 5.3 victories better than the 102.7 games that they were supposed to win. In fact, that PASE rate is less than one game per dance above expectations. Not only that, but mid-major/smalls have just an 11.6 average seed in the dance, compared to a 5.7 seed for power conferences. So we're not talking about the same quality of teams. In other words, the bar for overachievement is lower.

Consider: Between 1985 and 1991, the average seed of a non-power team was 11.0 -- yet they managed to reach six Final Fours and win two championships. Since 2006, mid-majors and smalls have made five Final Fours and have yet to cut down the nets.

Are the declarations of parity in college basketball a fact or a myth? The answer lies somewhere in between. Fewer non-power teams are making the tourney, but they are performing slightly better against seed expectations. Still, those expectations are somewhat lower considering their average seed, and it has been 23 years since the last mid-major took home the title. (That would be mid-major/pseudo-pro team UNLV in 1990.)

Put it this way: if Gonzaga wins the championship, I'll consider all the cries of parity valid.