Jonah Keri: If I had a Baseball Hall of Fame vote, here's how I'd vote this year

Sometimes, it is tough to separate art vs. artist. Here's how to do it in regards to the Hall

If you're a grown adult with any kind of a conscience, at some point you've probably run into the Art vs. Artist dilemma.

The idea behind Art vs. Artist is simple to understand, but tough to reconcile. Say you're a fan of a certain band. You like their music, you go to their shows, you buy their gear. Then at some point, that band does something really lousy. Maybe they release a song with racist and homophobic lyrics. Maybe they act like petulant jerks, causing their show to be cancelled and a riot to ensue -- after you moved heaven and Earth to get tickets and time off to go see them. Do you continue to support that band, because they're talented and entertaining? Or do you jump off the bandwagon, because some transgressions can't be excused?

We know all about this problem in today's sports world. Colin Kaepernick has angered legions of NFL fans because he took a knee during the national anthem to protest police brutality and racial inequality in America. Hundreds of other players have since followed Kaepernick's lead, raising the ire of fans who don't understand, or simply choose to ignore, the point of peaceful protest. At the other end of the spectrum, Curt Schilling angered many others by sending out racist memes, as well as cheering for slogans that threaten the lives of journalists.

If you're a 49ers fan who thinks Kaepernick should keep his mouth shut, do you block out the memory of any game started by your team's former quarterback? If you're a Diamondbacks or Red Sox fan, do you wipe the championship thoughts of 2001 and 2004 out of your brain, because Schilling played a leading role in both? Do you stand behind the Art, even if you grow to despise the Artist?

The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum is starting to inch into Art vs. Artist territory, albeit on a smaller scale.

As a museum, the Hall is wonderful. Getting a behind-the-scenes tour of the place last spring was an incredible moment for a baseball die-hard like myself. Seeing Tim Raines, my favorite player from my youth, tour the Hall with his wife and two daughters was a really cool moment. Getting to touch Babe Ruth's bat and ogle the ball hit by Ted Williams in the 1941 All-Star Game gave me chills. Aside from how much fun it is to absorb all of the Hall's exhibits, Cooperstown is an impossibly charming little village. A good friend of mine works for the Hall, and is as lovely a guy as you would ever hope to meet.

Despite all that, it's getting tougher and tougher to support the Hall's policies, and tactics, when it comes to who gains enshrinement and who doesn't. It was disheartening to watch as the Hall's voting body, the Baseball Writers Association of America, raised two very reasonable proposals last summer (raise the number of votes allowed per ballot from 10 to 12, and make every voter's ballot public), only to see them both shot down.

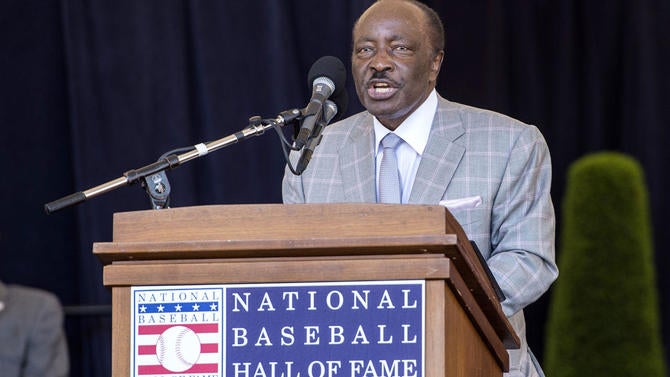

And then things got worse. Joe Morgan, vice chairman of the Hall's board of directors, wrote a letter prodding the BBWAA to snub performance-enhancing drug users from their ballots. The letter was infuriating for multiple reasons. It took aim at any player "who took body-altering chemicals in a deliberate effort," while completely ignoring the very real effects of amphetamines on player performance, and the thousands of players who took those performance enhancers for years. One of those PED users was Pete Rose, Morgan's long-time teammate who also earned Morgan's full-throated support for Hall induction, despite the fact that Rose admitted to taking amphetamines during his playing days ... and bet on baseball, as a manager and reportedly as a player too ... and allegedly had a sexual relationship with a girl under 16 years old when he was in his mid-30s.

The players Morgan had in mind, such as Barry Bonds and Roger Clemens, were the best of their generation, as well as two of the best of all time. Neither ever failed a drug test, because they played mostly during an era when MLB effectively condoned PED use by looking the other way; the current Joint Drug Prevention and Treatment Program didn't take effect until 2006, one year before Bonds and Clemens finished playing. Barring writers from voting for players like Bonds and Clemens whitewashes an entire era of baseball, and serves as revisionist history, given how happy MLB owners were to rake in millions and go full ostrich-in-the-sand mode during the height of the PED era. Hell, Bud Selig just got inducted into the Hall of Fame last summer, and he presided over all of this.

Read former New York Times writer Murray Chass on Morgan's refusal to stand behind his letter by offering any comments to inquiring media. Read Yahoo Sports writer Jeff Passan's piece explaining why Morgan's letter prompted him to stop taking part in the voting process. Consider all the ham-handed methods that have been used to prevent some of the greatest players of all time from being inducted into the Hall, while a horrible racist like Cap Anson has his bust prominently displayed in the building's plaque room. Hell, if we want to play the PED Hysteria Game, someone needs to explain how former pitcher Pud Galvin got inducted into the Hall despite his own, widely known use of performance-enhancing substances ... which occurred in 1889.

I still plan to visit the Hall and encourage you to do the same, because I love baseball and its history, and you could spend a week getting lost in the museum's incredibly cool exhibits. But the Hall's hypocritical, outdated and wrong-headed approach to handling the sport's past needs to improve. (In the meantime, if you're looking for a shrine honoring baseball's amazing past that doesn't come with the same baggage, the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City is a must-see.)

I have several years to go before I reach the threshold that grants me a vote for the Hall of Fame. But every year, I write about the players I would choose if I did have a ballot, so I'll do so again this time. Read my 2016 Hall column for more on the players who didn't make it last year who I supported then, and still support now. Those players are, in order of accomplishments: Barry Bonds, Roger Clemens, Curt Schilling (his art is worthy, even if the artist is deeply flawed), Mike Mussina, Larry Walker, Manny Ramirez, Edgar Martinez and Vladimir Guerrero.

Elsewhere, Trevor Hoffman is going to get in this time after gaining 74 percent of the vote last time, but as I wrote last year, a top starting pitcher or position player delivers far more value than an equivalent reliever ever could, so I wouldn't vote for Hoffman or Billy Wagner on this year's ballot. Jeff Kent and Fred McGriff highlight a list of players who also missed the cut, but gave us many unforgettable moments as All-Star standouts.

This year's ballot features two players whose induction I strongly support. Meanwhile, four other players make compelling enough cases to elicit further comment. Here then are some more thoughts on six intriguing first-time candidates.

Chipper Jones

My Hall of Fame picks boil down to numbers. Did the candidate so thoroughly dominate his era that his stats peg him as a worthy Hall of Famer? If he did, then he's in. My benchmark for such statistical evaluations is JAWS. Devised by Sports Illustrated writer Jay Jaffe, JAWS combines a player's career and peak accomplishments (the latter as measured by his seven best seasons), then spits out a composite score that incorporates both. Generally speaking, if a player flashes a higher JAWS score than the average Hall of Famer at his position, I'll support his candidacy -- though I'll occasionally make exceptions if a player comes really close, and/or if top-of-the-scale players skew the JAWS rankings (think Babe Ruth compared to other right fielders).

There's no ambiguity or doubt in the case of Chipper Jones. He's the sixth-best third baseman of all time according to JAWS, as well as an MVP and eight-time All-Star. The character clause in the Hall of Fame's voting language is so vague, it becomes essentially worthless ... doubly so when the likes of Cap Anson have already earned enshrinement. So a couple of ill-advised tweets do absolutely nothing to affect my opinion of Chipper's candidacy. He's in, easily.

Jim Thome

Six hundred and twelve career home runs, a batting line of .276/.402/.554 that shines even in the context of the PED era, and the greatest character in internet history. A lock.

Scott Rolen/Andruw Jones/Omar Vizquel

Defense has always been a tricky commodity to evaluate. Hits and home runs are easily measurable and countable. But defense can't be counted so simply. If an infielder fields X number of groundballs in his career, we have to take into account everything from the groundball tendencies of his pitching staff to how deft a fielder the guy playing beside him might have been. Plus, the further back we go in history, the less sophisticated our fielding tools become, making proper evaluation that much tougher.

Here's what we do know: Scott Rolen, Andruw Jones and Omar Vizquel were generationally great fielders, ranking among the best of all time at their positions. If Ozzie Smith could gain election into the Hall based mostly on the strength of his defense, we have to at least consider Rolen, Jones and Vizquel as candidates too, given their magnificent performances with the glove, as measured by both statistical analysis, and the informed opinions of the talent evaluaters who watched them play.

Thing is, there's one big difference that separates one of the three players from the others. Weighted Runs Created Plus is a stat that measures a player's offensive performance as compared to other players of the same era. A score of 100 means exactly league-average production; 110 would be 10 percent better than league average, 90 is 10 percent worse than league average, and so on. Let's compare the three:

| Player | wRC+ |

|---|---|

Scott Rolen | 122 |

Andruw Jones | 111 |

Vizquel | 83 |

... and just for kicks:

| Player | wRC+ |

|---|---|

Ozzie Smith | 90 |

Yes, Vizquel was more durable than Rolen or Jones, so much so that he started more games than any other shortstop. But he wasn't in the same universe as either one as a hitter. Once you adjust for era, Vizquel wasn't the hitter that Smith was either ... and he certainly wasn't anywhere near as good defensively, because Smith generated more value with his glove than any player in baseball history.

By JAWS, Rolen was the 10th-best third baseman of all time, above the average threshold for a Hall of Famer at his position. Jones rated 11th among all center fielders and slightly below average for his position, but that ranking is skewed by only seven primary center fielders ever making the Hall, with Willie Mays, Ty Cobb and Tris Speaker being so good, they throw off the scale. Jones comes in just ahead of a trio of existing Hall of Famers in Richie Ashburn, Andre Dawson and 19th-century star Billy Hamilton. Meanwhile, Vizquel ranks all the way down at 42nd among all-time shortstops, sandwiched between Rico Petrocelli and Dick Bartell.

Rolen and Jones are tough calls, and a case can be made for or against each of them. I would vote them both in, barely. Vizquel was a great player who also has no case for the Hall, unless we start grading players based on whether or not their headless baseball cards were ever traded for Mutton Chop Yaz.

Johan Santana

He doesn't have the longevity to make it, as you can see when he slots in between Frank Tanana and Wilbur Wood. Still, we should remember two things about Santana. First, he was the best pitcher in the league three years in a row, putting up incredibly stingy numbers from 2004-06, right at the tail end of the PED era.

Second ... you already know.