Sandlot baseball in Chicago is light on rules and adults, and that's what makes it great

During an era of highly organized youth sports, one league is indeed letting the kids play

CHICAGO -- The hope going in was that an argument, any argument, would span at least two minutes. One of Jim Price's few rules is that if an on-field dispute lasts that long, then the team captains settle the matter in the determinative crucible of "rock, paper, scissors." Alas and alack, that doesn't happen. A brief dispute breaks out in the second inning over a checked swing, but it peters out after just a few seconds.

Other arguments bubble up -- which team gets Marcus after he shows up late, for instance, and whether a runner who just beat out a grounder is out because he made his way back to the first-base bag via fair territory ("That's not a rule, but I guess it's their rule," quipped Price) -- but are swiftly resolved. Before the first game, Cody said sandlot was cool because they got to make up their own rules, and this is perhaps an on-the-fly example of that particular virtue.

Although the author wasn't in position to glimpse the particulars, word spreads that the younger kids on the other diamond resorted to "rock, paper, scissors" before their two minutes were even up. "Why argue when it takes away from time spent playing baseball?" seems to be the evolving rationale.

This is sandlot baseball, and it persists on the north side of Chicago despite, it would seem, a number of cultural currents pressing in the other direction.

Price is the owner and operator of Bash Sports Academy in Chicago, an indoor baseball and softball training facility from which Price runs camps and in which teams can train during cold-weather months. Since opening his business 12 years ago, Price developed close relationships with many coaches at the youth and high-school levels, and in his conversations with them a common theme emerged -- a lack of leaders on their teams.

Part of this, of course, is the skewed perceptions that afflict every generation when assessing the younger cohort. Another part of it, though, is likely the shift from "free range parenting" to the hyper-involved model that currently prevails. Both approaches have their merits and demerits, and it's never very simple to separate causation from correlation with regard to how kids come out on the other side of our efforts at stewardship. Many will agree, though, that the current generation of kids has seen their sense of independence and autonomy whittled away at, perhaps to an unexampled extent. Price, at least in the sub-realm of baseball, is here to help them get it back.

In his work, Price over the years noticed that the kids funneling through his facility weren't organizing games on their own. Only with the prompting or at times prodding of adults -- and only under the constraints of organized leagues -- were they playing baseball. At the same time, the rise of travel baseball was shunting aside the kids who maybe weren't as skilled as the travel players but whose enthusiasm for the game rivaled or exceeded anyone's. He began casting about for ideas, often with those kinds of kids in mind. He landed upon sandlot baseball, in the vintage sense of the term.

When the idea was still percolating, Price reached out to a childhood friend with whom he'd played countless improvised, slapdash baseball games decades prior. "How did we do it?" he asked.

After conversations and thought, he landed upon some rules:

- At least six players per team (yes, you can play 6-on-6 -- use your fielders how you want).

- Lob-pitching, so that strikeouts are minimized and balls in play are maximized.

- No walks.

- No catcher and thus no stealing.

- Two-step lead-offs maximum.

- Kids pick the captains, and the captains in turn pick the teams.

- Each squad picks a team name, but the team name can't be that of an MLB team or notable college squad (creativity is encouraged).

- Kids are responsible for keeping up with the score.

- Kids are responsible for making their own calls and enforcing the rules (even if their rules are not the correct ones).

"All I did," Price explained, "was think about how it was when I was a kid."

Through trial-and-error he later landed upon other rules -- like "rock, paper, scissors" as the grand arbiter of disputes. By design, though, rules and structure were kept to a minimum.

When told of Price's sandlot league, Dr. Dan Gould, director of the Institute for the Study of Youth Sports at Michigan State University, says he's "very pleased" to hear of its existence. As Gould sees it, children born after 1996 or thereabouts lost some of their fledgling autonomy because their parents were with them far more often than were parents of prior generations. This generational shift is in part owing to how we take in media these days and consequently how tragedies befalling children -- criminal in nature or otherwise -- occupy outsized territory in our minds. That leaves little space for contemplation of the chances of such things ever happening to your child.

Cultivation theory was originally about television, but the distorting effects thereof also apply to internet media consumption, maybe especially to internet media consumption. We often believe the world is how it's presented to us through the lens and not how we see it when we're actually out in the world. This isn't a particularly novel explanation, but there's truth to it.

Another factor, according to Gould, is the decaying American confidence. Parents no longer necessarily believe their children will be better off than they were, and often blame or credit for a child's failures or successes will accrue to the parents, even when it shouldn't. This fear-based dynamic has led to what Gould calls "snowmobile parenting." Whereas "helicopter parents" merely hover and observe in a state of ubiquity, the snowmobile parent clears a path in front of the child -- free, as much as possible, of obstructions and challenges. Given the forward-looking pessimism of the day, parents feel their children need such constant advocacy. "Independence eventually gets lost," Gould says.

Leading up to the first season of Price's sandlot league, he handed out flyers at little league and travel games and spread to the word to kids coming through his facility. In that inaugural season three years ago, all the kids were lumped together, but as more kids began showing up and the age range widened, Price audibled and split the kids up into two groups: ages 8-10 on one field and ages 11-14 on another. An early good sign was that parents who were dropping kids off at the games by and large didn't try to hang around and watch. To Price, that suggested they understood what he was trying to accomplish. Price got another inkling that his idea would take once "the bike brigade" began showing up -- kids free of parents showing up in packs on their bicycles. The bikes formed a gaggle near the edge of the field as a symbol of the roaming instinct that seemed plucked from an earlier time. Price knew something was working.

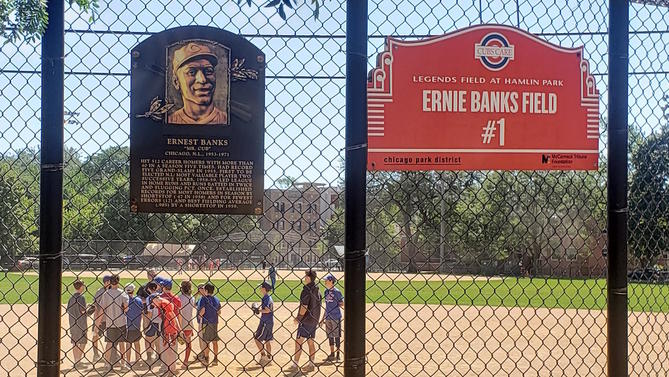

The games rotated among three North Side parks, depending upon availability -- Welles, Revere, and Hamlin. On a Friday in August, Price, two college students tasked with keeping the scorebook and otherwise staying out of the way ("Grown-ups are here to make sure there's no stray dogs," Price explained) arrived at Hamlin Park and waited for the kids to trickle in.

Mostly, it was a gathering of regulars. Keith is the relentlessly honest one, inclined toward unsolicited confessionals in the field and on the bases that occasionally do his team harm (he once told on himself for not having his foot on the bag during a play at first base, to the dismay of his teammates). There's a "Sportsman of the Day" award, voted on by the kids, that incents such charming traits. Marcus, to his enduring credit, seems to be the merchant of chaos (he shows up late and touches off a brief debate over whose team he'll be on, and he plainly enjoys it). Jackson is one of the oldest and the one who gently nudges the game back on the rails when necessary. Bennett is the kid who sits on the second base bag between at-bats. Cody is the current "King of the Sandlot" -- i.e., the points leader based on how often one's team wins and other performance-based incentives. (Coming into this day, 78 different kids across both age groups had authored at least one King of the Sandlot point.) Others fill shifting roles as the game meanders toward its conclusion. A couple of kids wear baseball pants and cleats, but otherwise shorts and gym shoes abound.

In keeping with the ethos of the man for whom the field is named …

This will be a doubleheader. "Who does this game belong to?" Price asks as his weekly refrain before sending them away to the field. "Us," or "The kids," or, less than correct, "We," they answer in something like unison.

"I call not being captain," one kid proclaims. Eventually, the kids settle on two captains, and teams are chosen. The draft order seems to bear at least seem correlation with height.

In the first game, the respective captains pick their team names -- the "Knockoff Cubs" versus "Triforce" (the latter is a "Legend of Zelda" reference, the author was informed).

What you notice straightaway is the abundance of banter during the game, which sets it apart from the weighty on-field silence you find at league and travel games these days. Sure, in those organized contests you get kids calling out the number of outs, often at the coach's urging, and that sort of thing, but the conversational element is typically lacking, mostly because kids feel they should exude seriousness and a sense of purpose. Those games count, after all.

Sandlot, though, at times feels like a bunch of friends watching a game while they happen to be playing in it. "Oh," says one following a rare pickoff attempt, "you're not Jon Lester anymore?"

"If you don't get a hit, I'm suing you," says another later on.

"Why would you swing at that?"

"That was supposed to be an RBI."

"You should let someone else pitch."

And:

"Use a different bat."

"Why?"

"You're early."

"OK."

"See what I mean?" after the kid doubles with his new implement.

Speaking of bats, after the first couple of innings you can glimpse the surest sign that this is a game unfolding without any adult-imposed sense of order and propriety:

Such a disarray of bats may lead one to accuse these kids lacking attention to detail. Really, though, the bats are there not because of indolence but rather because the focus is singularly on playing baseball and not tidying up. Such a scene could drive coach or umpire to perform acts of sanction and reprisal, but, well, they weren't invited.

The players' interactions with Price and the college-aged scorekeeper are rare, and that's of course as intended. "What's the score?" from a player who believes he's lost track is one exception.

"We know. Do you?" Price responds.

"2-1?"

"You got it. Call it out."

Another of Price's refrains draws strength from its imprecision: "Figure it out" -- whatever "it" is at the moment. That became his go-to bit of instruction in the first year of sandlot, when he learned the most important thing: to not let the kids pull you into the game. "They are so conditioned to want an grown-up to make decisions for them that they will look at you after a close play, or a kid will come over and complain about where he's been assigned to play by his captain," Price says. "Make them figure it out."

The kids, at least on this day, invariably do figure it out with Price merely watching on. The writer is reminded of what a friend's father once said to his son when he first left for college back in the early 1990s. "I'm still here for you," the father told him, "but I'm not here for you."

An easy assumption to make is that it takes a certain kind of kid to enjoy sandlot and its nebulous boundaries. You need to be comfortable away from your parents and among a peer group of kids you've possibly never met before. You need to be confident enough in your baseball abilities to commit to them in front of that peer group. You need to be OK with the possibility of being chosen last. When a dispute inevitably arises, striking a balance between self-advocacy and respectful acknowledgement of the other side is vital. You need to be able to handle failure and defeat without being reminded by an adult voice that you need to be able to handle failure and defeat. The same goes for success and victory.

Here's Dr. Dan Marullo, pediatric psychologist at Children's of Alabama, with a germane observation he made to The Romper in April of 2019:

"An 8-year-old playing baseball with their friends negotiating whether the ball was foul or not, those are skills they're learning about how to interact with people. It's no different than the 4-year-olds tussling over the same toy, but if you don't have those experiences when you're 4, it's harder to build on when you're 8, and then 16. That's why play is so important."

If a kid hasn't cultivated those skills by the time an opportunity like sandlot comes around, protective impulses on the part of the parent -- generationally unique or otherwise -- could take over. Dr. Gould of Michigan State sympathizes but believes it's not too late for kids to have their sense of independence tested and subsequently strengthened. "Sooner or later it's going to happen -- being alone," says Gould. "It can be on a baseball field or it can be out in the real world later on, but it will happen."

Even if a child may not have those foundations at age four, five, six and recoils from peer-driven activities such as this one, better to leap into this shallow end, as it were, with someone like Jim Price at the margins to ensure no fights break out or no 18-year-old bullies turn up or other forms of mayhem find their way into the game. That particularly appeals to Gould. "There's too much structure in youth sports today, generally speaking, and this sandlot idea manages to remove a lot of that structure while still providing a safe environment. I think it's excellent."

Now back to the game. As sometimes happens, team selections informed by preexisting friendships and eyeball appraisals of baseball skill yield one-sided results. So it is in the first game, as the Knockoff Cubs prevail over the TriForce by a score of 18-5. For the second game, new captains are picked, and the rosters are scrambled in the hopes of a fairer fight. Then comes the delicate negotiation of choosing a team name. "The what?" Price says to Cody. "Spell that."

He does. Cody's team is the Slap Butt Cheeks. Presumably the name is a directive to slap butt cheeks as opposed to butt cheeks capable of slapping, but either makes for a commendable choice. The other team is the Heimlich Maneuver. For reasons sufficient unto the higher levels of organized baseball, neither name is presently being used by an MLB or major-college team, so they pass muster with Price.

When selective hitters like Jackson come up, you notice the secondary genius of Price's no catcher rule. The rule was implemented to eliminate stealing, which is a poor fit with the lob-pitching environment, and to obviate the need for catcher's gear. Another pro of not having a catcher squatting behind the plate is that the hitter must retrieve the ball after thinking better of a particular pitch. Even the most discerning batsman -- the kid who gives the pitcher specific instructions on where to put the ball (à la professional baseball before 1885) -- grows quickly weary of unwinding from his coiled stance to go retrieve the ball from the backstop. If that built-in incentive doesn't get the bat swinging, then the inevitable "come on, hit the ball" peer directive from the field surely will.

One of Price's strongest temptations to intervene in the early days of his sandlot league was the length of between-inning breaks. Kids would spill out of the dugout, debate who would play which position (in the event that the captain didn't give such instructions), chirp at each other, and throw the ball around the horn again and again. This, as Price learned, was perhaps the training wheel that was hardest to remove. Without an umpire to give them a "play ball" or a "batter up," the kids would sometimes play catch longer than what seemed reasonable. What's the harm, Price finally told himself. Sure enough, they figured it out. Eventually, a player would say, "OK, let's play," and after enough reps of this sort of thing, the regular participants developed a feel for how long those breaks should last. In this one, the span between the third out and the first pitch of the following frame feels like that of a league game.

As the sun gets higher and the time ticks by, the haphazard grows in power. Marcus switch hits for the first couple of pitches of an at bat, and after some ungainly swings -- his righty swing calls to mind the action of a spring-loaded plunger of a pinball machine -- his bench persuades him to drop the experiment. He swiftly doubles from his natural left side, but that's abetted by the fact that the Heimlich Maneuver, down to seven players, has curiously opted to go without a center fielder. This proves a poor decision, as the Slap Butt Cheeks inflict a 14-run inning upon them. As the margin gets comfier, runners approaching the plate take their time touching it -- dancing as the ball makes its way back home-ward or, in Marcus' case, dusting off the plate with his batting gloves as a fielder in possession of the ball rushes toward him for the tag (the lack of a catcher also requires the pitcher to cover the plate when circumstances warrant -- and they often warrant).

One kid patrolling a wide swath of outfield makes a game attempt at the almost never glimpsed 7-3 putout, and he almost succeeds. Jackson, a darn good baseball player but not an especially hasty one, barely beats it out, and the throw from left to first, soaring over the cutoff man like a bird evading a land-bound predator, allows the runner to score from first. That's the kind of thing that would earn the outfielder in question a dugout lecture in a more formal setting, but it says here that the world needs space for 7-3 putout attempts.

With the score 16-2, the players agree that it's time to call it, albeit before the minimum number of innings have been played. "OK," says Price. "It's your game." As though written in the stars and or ancient sacred texts, the Slap Butt Cheeks have triumphed.

There's time for a third game, which won't count in the King of the Sandlot standings and which -- on account of its unofficial status -- lamentably won't involve team names. Right away, "dog interference," is the call from the second baseman:

The dog interference call, however, doesn't lead to any stoppage of play, which feels like how things ought to be. When a second dog later luxuriated itself in center, no one even made mention of it:

At this point in the day, disputes are resolved by brief displays of doggedness -- this is not a punning of the above -- no matter how absurd the argument. For instance, after Marcus whiffs on the first pitch of his at-bat, fouls off a pitch, and then whiffs on another, he retroactively insists that the first swing was part of his "warm-up routine" and thus not a true strike one. The team in the field understandably objects, but Marcus remains in the box and in his stance, waiting for the next pitch, and finally something like apathy prevails on his behalf. He singles. "In sandlot everything is what it seems to be," Price says around this time.

Not long after, the team in the field makes their way to the dugout after the second out of a long frame. The team at-bat protests that it's just the second out. "We're ready to hit," says the third baseman. "But that's just two outs!" someone says. The fielding team continues to amble off, and finally the on-deck hitter relents. "Fine." Not long after the noon hour arrives, and this particular three-hour sandlot sessions -- the last one of 2019 -- is over.

"It's fun," Marcus says after the final game ended. "It's fun because there are no parents."

And why doesn't he like parents there? "Because they make the game more lame."

"I liked it because there were no bad umpires," says Wyatt. Most righteous outrage at the youth baseball level flows from the strike zone, so it's really the lack of called balls and strikes that he's celebrating. The umps, though, will forever be a tidy foil.

The league stalwarts, Jackson and Keith, see a different class of merits -- what's there instead of what isn't there. "I like that it's just something to do every Friday in the summer," says Keith. "It's fun to play with with these people that I know for like three years."

"I like what Keith said," says Jackson. "Every Friday you get to interact with people. You make new friends. You know, you have fun. You get to make the rules. It's a competitive game, but it's just really fun."

Over the course of the day, you've seen some good baseball. At this age, they're fairly adept at tracking fly balls, and one kid who's a regular at third base has a powerful and accurate arm that belies his slight frame. However, halting swings and tentative, outside-the-feet approaches to ground balls have also been observed. This goes back to one of Price's first principles: that this is for kids who have a desire to play, first, and skill, second. You don't see the almost-palpable frustration after a strikeout or error (not that we're keeping track of errors here) that's an unfortunately reliable presence when the eyes of coaches and parents are watching. No one is here by dint of compulsion, or if they are they don't show it.

"My hope," Price says as the kids file out, some to waiting bikes and others to parents who've just arrived, "is that these kids will start doing it on their own."