Coaches echo Tony Dungy's comments about the good but flawed Rooney Rule

It's long past time to make tweaks to the NFL's process of hiring minority head coaches

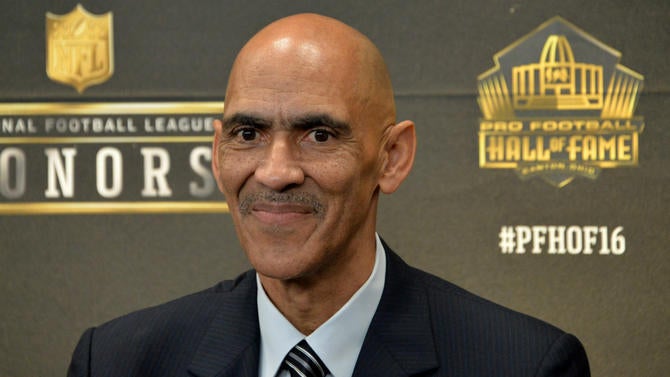

With any luck, the recent comments by Hall of Fame coach Tony Dungy revealing some of the underlying flaws of the Rooney Rule will be the precursor to some significant alterations in the language and nuance as to how the regulation operates. Even if it is not, his candid remarks put a distinguished and accomplished face to the plight so many African-American coaches continue to face, and have made the Rooney Rule a part of the football discourse at a time it is usually forgotten.

Because the reality is this: if we only truly contemplate the fairness and equity of front office and coaching hiring practices in the NFL during those weeks in January when the hiring and firings actually take place, amid a whirlwind of activity and occasional chaos that punctuate that time in the NFL schedule, then we are doing a disservice to the process and the men involved in it. Kudos to Mike Sando at ESPN.com for the efforts he put into studying the problem, and his terrific piece putting the issue into statistical context. But the mere fact that such articles are still needed is somewhat troubling on its own.

The fact that, as I found along with Sando, that most current African-American coaches are still only comfortable talking about the Rooney Rule and their experiences with it in an anonymous nature speaks to the inherent divide that still must be overcome. That fact that it takes someone like Dungy -- happily retired with no desire to get back into the game -- to speak somewhat openly about the conundrum facing his contemporaries still in football, is a statement unto itself.

Sadly, certain prevailing truths remain.

'I knew I wasn't getting that job. Everyone knew it.'

Every year, some team or teams end up picking an African-American coach from their staff to interview, and then quickly go on to hire from outside. It speaks to the flawed nature of the current construct. Frequently African-American interim head coaches have excelled during their brief opportunities at the job, such as Todd Bowles with the Dolphins, only to eventually be passed over for the actual job a few weeks later. It's a phenomenon that seems particularly troubling to me.

"You are really stuck between a rock and a hard place," said one former African-American NFL coach who took part in at least one head coaching interview for his employer at the time for which he did not feel he was actually a candidate. "You have the pressure from the Fritz Pollard Alliance to take any interview you are offered 'for the good of the cause,' even if you felt like you are just being used. So you don't want to let them down, and the Rooney Rule has helped some people and you know there is always that remote chance that you are that Mike Tomlin guy who ends up getting the job when no one thought he would ... But at the same time you don't want to be 'that guy' who just takes all the Rooney Rule interviews but isn't going to get any jobs.

"And then you would have people or your agent telling you, 'What can it hurt to interview?' And you do gain experience from it, but in my mind I was also insulted. I went into several interviews knowing I wasn't going to get the job, and it's not like the guys I was losing out to were Nick Saban or Bill Belichick. It was usually coaches who hadn't accomplished all that much and who really never went on to do much when they got the job. In my mind it was like, 'I would have got those interviews anyway, even without the Rooney Rule,' and you hate to feel like it was a token opportunity because of it."

Another former African-American coach detailed a similar experience and conflicted feelings from his Rooney Rule interviews. On one occasion, he informed team officials that he did not want to take the interview if it was "just a Rooney Rule interview," and rebuffed their overtures several times. They were persistent.

"I made it clear I didn't want to just do a Rooney Rule and (the team president) was like, 'No, we would never do that to you,'" the coach said. "'You've done a great job here, the players love you, the other coaches love you. You're a rising star. You have a very real opportunity to get this job.' So finally I said, 'OK.' And they fly me and another candidate to the owner's house and it's like a quick interview. It's like, 'Let's just get this over with.' It was quick, man. It was like, 'Boom, let's go get the guy we really want to get.'"

Another coach mentioned a time he knew he was being used to fulfill the Rooney Rule, was more or less coerced by a team official to do so, and then watched as the owner checked and fiddled with his phone when the actual interview took place.

"I knew I wasn't getting that job," the coach said. "Everyone knew it. We didn't even have a GM hired yet. Everyone is making good money now -- the position coaches and coordinators -- and you can only say so much. What can you really do about it? What can you do? A lot of these jobs, you already know who they're going to hire anyway -- or at least who they want to hire -- and you know that. We all know each other and we all talk. But in the end you end up doing the interview because that's the way the game is played."

In the front office ranks, the process hasn't done much to advance the careers or true GM prospects of men like Lake Dawson, Marc Ross, Morocco Brown, to name a few. Frankly, things look fairly bleak for the bulk of the men in this situation.

Branching out from the same old candidate pool

Football is a game played at the highest levels, increasingly, by African-Americans. Yet the opportunities for growth and advancement in head coaching and general manager positions are not only not nearly keeping pace, but actually seem to be dwindling each offseason. Far too often teams seem to be identifying and latching on to one or two Rooney Rule guys and interviewing them en masse, but far too few coaches are actually benefiting with a job on the other end of it.

In the past several hiring cycles, owners and GMs looking for coaches have fallen into a lazy groupthink that virtually only offensive play callers (i.e. offensive coordinators and quarterback-guru types) are worthy of head coaching jobs. Few African-Americans get to wear that offensive coordinator hat in the first place, and it systematically ignores the host of great minority candidates on the defensive side of the ball, to say nothing of special teams.

It looks like the ol' boys club, all over again.

"Too frequently, we don't look at leadership, we don't look at getting the most out of people, we don't look at bringing people together and staffs together -- all those things that you need to be a head coach," Dungy told ESPN.com. "It is an inexact science. It is done in an inexact way. Look how long it took Bruce Arians to get a head-coaching job; it is not just with minorities.

"But I think when you are a minority coach, you have even that added burden, or added handicap of not always being highly publicized. For owners who do not know what they are looking for, it is much easier to say, 'Well, I'll take Candidate A because at least everybody knows him and everybody will say this is a good hire.'"

As Sando points out, Bowles (Jets) is the only first-time minority head coach hired in the past five offseasons, while 21 first-time white head coaches got jobs. And with 80 of the league's 85 offensive coordinators, QB coaches and offensive quality control coaches as white, and the preponderance of head coaches already white, it's difficult to see how the next wave of African-American coaches is being cultivated, and when this cycle will be stopped. What's far more certain is that the rule is not operating fully in the spirit by which it was developed, and that much more needs to be done to make sure the coaching rosters start to resemble the playing roster.

(And don't even get me started in the front office ranks, where the prospects are beyond bleak for most non-whites. Several GMs and top coaching agents I spoke to have difficulty coming up with three-to-five names of minority candidates who could be trumpeted as true leading candidates right now. It's an indictment not on the many great minority scouts, assistant GMs and executives in the league, but more on the lack of attention, push and recognition many of them seem to receive, and the systematic failure to allow them to take the reigns of NFL teams.)

To interview or not to interview?

Where things really seem to fall apart -- vis-a-vis what this rule is supposed to accomplish in theory versus how it is applied in practice -- is when an individual is put in the position of being asked to interview for a position that he and his team know in their hearts he will not get.

What would you do?

It's when someone already on the staff, fully realizing while he may be valued by his current employer to some degree but not nearly enough to actually be named the head coach, is asked to interview almost immediately in the process, knowing full well someone else (in almost every case a white male from another organization) will be the one actually hired. On rare occasions, that nominal "candidate" already on staff complies with the process, which ultimately does a disservice to all involved.

But what are the alternatives?

If you don't play ball, then you run the risk of getting blackballed. These interviews are difficult to land in the first place; the experience gained from them is supposed to better position the candidate for other opportunities down the line, and all of this is meant to bolster diversity. You don't want to aggravate owners or alienate yourself, but you also don't want to allow yourself to be used, to take part in something that feels like a sham, to lessen your worth by being complicit in a process that is basically allowing a team to check a box but may in the end be deleterious to the coach involved.

"The good thing about the Rooney Rule was not that you had to interview a minority candidate but that it slowed the process down and made you do some research," Dungy said. "But now it seems like in the past few years it has become, 'Just let me talk to a couple minority coaches very quickly so I can go about the business of hiring the person I really want to hire anyway.'"

Things don't seem to have advanced that much for men like, to name a few, Jerry Gray, Ray Sherman, Eric Studesville, Harold Goodwin, Perry Fewell, Ray Horton, Mel Tucker, Greg Blache and Duce Staley -- who in some cases were asked multiple times by their current team to interviews for head coaching jobs they were never going to get. In some cases, those men were asked by more than one organization.

When you see verbs like "satisfy" and "comply" used so often in regard to these interviews, especially in cases such as these where the team is clearly casting a large outside net at numerous "hot" white candidates, things can get particularly uncomfortable for those individuals involved, and even to a lesser extent those who have to chronicle the process in the media.

Perhaps expanding the requirement to two people of color (and/or a female) would force teams to pump the breaks on some immediate hires, actually go outside their own staff to talk to a rising African-American coach from another staff, and push us closer to the intent of the Rooney Rule as originally constructed. With so little real progress being made toward the overarching goals of the Rooney Rule, it puts massive pressure on those African-Americans who do make it to the head-coaching plateau to try to pull as many other minorities up as they can on their staffs, but that is an unfair burden as well. If the coaching ranks remotely resembled the playing ranks, that cross wouldn't fall so deeply upon them.

Regardless, it needs to be something that is not just studied or talked about behind closed doors by the Competition Committee. Diversity needs to be more than a buzzword that is thrown around liberally by league officials and mentioned by the commissioner as a goal at annual league meetings.

The NFL requires a more clear and delineated path to actually achieving a better system, and while the Rooney Rule, as it currently stands, is a blueprint of sorts, it clearly needs to be buttressed and altered so that steady progress is being made. We need more Tony Dungys to get their chance; passing the same African-American candidates from team to team, year after year, is falling far short.