Jadeveon Clowney arrived at South Carolina as the No. 1 recruit in the 2011 class. (Getty Images)

The calendar has turned to February and another NFL season is at an end, which for football fans can mean only one thing: It's time again to congregate at the altar of national signing day, the holy hour of the recruiting-industrial complex, when thousands of high school seniors are finally allowed to convert their coveted, hard-won verbal commitments into binding signatures that lock them into the system. For a certain subculture, recruiting is a year-round obsession. For the rest of us, the next 48 hours will belong to largely anonymous but promising 18-year-olds in gyms and libraries, enjoying what may be their first brush with fame outside of a handful of websites, and maybe their last.

And yet, in all the hours of coverage, of all the questions asked and stories written to herald the arrival of the next generation, the hardest to answer may be the most fundamental: Do the recruiting rankings reinforcing this annual exercise in hyperbole actually matter? You know, do they work? At times, the insular world of recruiting and the emerging media machine that helped create it can seem like ends unto themselves -- rankings and analysis for their own sake, disconnected and unaccountable to future returns on the field. With the anticipation of the blue-chip signature that will make or break a class in the eyes of the big recruiting sites comes an implicit, longstanding suspicion that signing day is a well-packaged production of sound and fury, signifying nothing.

Anecdotally, it's not hard to reach that conclusion. We're coming off a season in which the Heisman Trophy was won by an undersized quarterback, Johnny Manziel, who slipped through the cracks a three-star afterthought. Another finalist for the award, Kansas State's Collin Klein, was passed over by virtually everyone, including schools in his home state of Colorado, only to lead a team full of castoffs and transfers to a Big 12 championship over the likes of Oklahoma and Texas. Wisconsin, never a recruiting power in the Big Ten, has claimed three conference titles in a row. In the past five years, BCS bowls have featured such non-entities on the recruiting trail as Boise State, Cincinnati, Connecticut and Northern Illinois. The starting quarterbacks in Sunday night's Super Bowl, Joe Flacco and Colin Kaepernick, rose from the obscurity of (respectively) Delaware and Nevada, two of the few schools that showed any interest. Ryan Perrilloux, Bryce Brown, the USC Trojans: Recently history is littered with once-touted flops, all of them hovering ominously over the proceedings like the ghosts of signing days past.

That's one way to look at it. Frankly, if you enjoy needling "experts" and other arbiters of authority, it's the fun way. Unfortunately, it's also shortsighted: Beyond the vagaries, the hype and the busts, the annual recruiting rankings still represent the most reliable system at our disposal for making initial assumptions about teams and players alike. Taken as a whole, the numbers actually do work -- as long as you're willing to use all of the numbers.

Manziel was a 3-star prospect. (US Presswire) |

Not to take all the fun out of it, but in practice, drawing conclusions from recruiting rankings is the rough equivalent of selling health insurance. Both industries are in the business of predicting the future on a large scale -- of making bets, essentially -- and both have sound, proven criteria for guaranteeing they bet right more often than they bet wrong. Occasionally, of course, certain individuals will defy that criteria: A lifelong smoker who eats fast food every day may live to be 90 years old. A vegetarian who exercises every day may suddenly drop dead at fifty. But when you're dealing with large groups of individuals, say, 1,000 smokers vs. 600 vegetarians, then the results become very, very predictable.

Recruiting operates on the same question, with measures for size and speed standing in for health risks. On a player-by-player or even team-by-team level, guessing who specifically will or will not live up to the hype, or will thrive despite a lack of hype, is almost always a fool's errand. But the foundation underlying those predictions remains remarkably stable. The key is to think in terms of groups, not individuals.

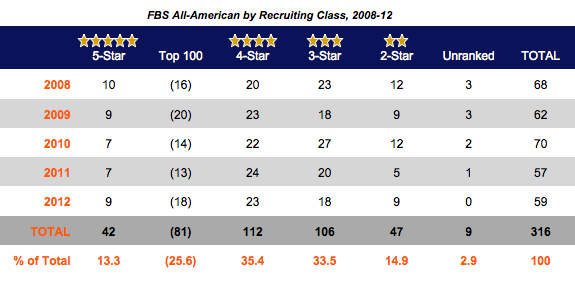

Assessing Individual Rankings. Take All-Americans, for example, the best measure we have for assessing individual success at the college level. Over the past five years (from 2008 to 2012), 316 players have been named to at least one major All-America team. Of that number, only 42 of them -- barely 13 percent -- arrived on campus as can't-miss, five-star prospects according to Rivals.com. Only 81 of them (around 25 percent) were ranked among Rivals' top 100 prospects in their respective recruiting class.

By contrast, twice as many All-Americans in the same span (162, more than half of the total) were regarded as mere three-star prospects or worse. According to the gurus, the top dozen or so recruiting powers in the country should field more talented rosters than that by themselves, right?

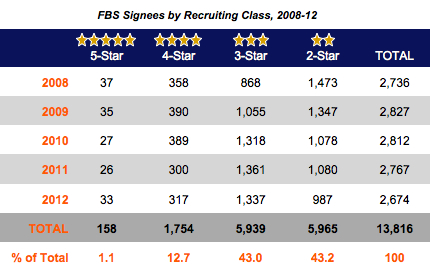

Only if your standard allows for zero margin for error, in which case you may as well stop reading. Fortunately, because we've been bestowed by the American education system with the magic of basic arithmetic, we do know better. If you look more closely at the relationship between initial expectations and eventual production, there's a very good reason for that, beginning with the distribution of stars at the beginning of the process. According to Rivals' database of signees to FBS schools over the last five years, the vast majority of incoming players are afterthoughts relegated to the lower reaches of the rankings:

It's impossible to judge the recruitniks fairly without acknowledging that two- and three-star recruits account for more than 86 percent of signees nationally, most of whom were either lightly scouted or not scouted at all. (In Rivals' rankings, all FBS signees are automatically assigned at least two stars; there are no "one-star" prospects, leaving walk-ons as the only players unaccounted for in the database.) The results change dramatically when you look at the All-America numbers in light of those ratios:

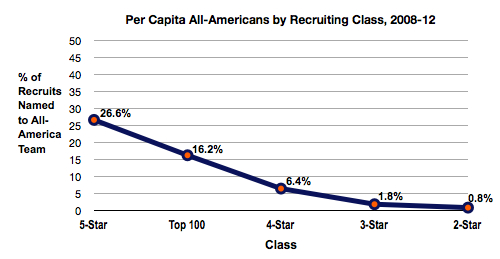

By comparing the number of incoming signees from 2008 to 2012 to the number eventually honored at the highest level, we can arrive at these odds:

Odds of Becoming an All-American, by Recruiting Ranking

5–Star: 1 in 4.

Top 100: 1 in 6.

4–Star: 1 in 16.

3–Star: 1 in 56.

2–Star: 1 in 127.

All FBS Signees: 1 in 45.

Or, a more succinct way of looking at it:

Maybe a raw ratio of 1 in 6 for top-100 prospects -- or whatever the "adjusted" number is after accounting for the early departures, injuries and academics that the rankings make no attempt to reflect -- isn't all that impressive by itself. After all, that means more elite recruits are falling short of their star-studded birthright than are reaching it. By definition, mediocrity is the norm across the board, but if you think of a highly-touted four- or five-star recruit as a guy who is supposed to become an All-American -- and a two or three-star guy as someone who is definitely not supposed to become an All-American -- then, yes, the rankings frequently miss.

On the other hand, if you consider the initial grade as a kind of investment -- a projection of the how likely a player is of becoming an elite contributor compared to rest of the field -- in that case, you'd put your money with the "experts" over the chances of finding the proverbial diamond in the rough every time.

Alabama's Dee Milliner. (US Presswire) |

OK, fine. But for the skeptics, maybe still a little narrow. If you play to win the game, shouldn't the validity of recruiting rankings hinge on, you know, wins?

Obviously. So let's look at the records.

Assessing Team Rankings. To do that, we have to start by creating a way to measure what the rankings project for each team. Using the "star" scale in a slightly different capacity, I classified all 68 teams currently residing in one of the "Big Six" conferences (the ACC, Big East, Big Ten, Big 12, Pac-12 and SEC) along with independents Notre Dame and BYU into one of five "classes," based on each team's accumulated recruiting rankings over the last five years, from 2008 to 2012.

Here, I only allowed for one exception: Alabama, which has claimed the No. 1 recruiting class in the nation in Rivals' estimation four of the last five years. As a result, the Crimson Tide's numbers are so far ahead of the rest of the pack in that span that they effectively constitute a class of their own. Of course, the corresponding results on the field make the Tide the single most compelling example of the rankings' success as a tool for predicting outcomes. At the same time, though, Bama has so vastly outperformed even its most well-heeled peers in those rankings that it would be frankly misleading to group them under the same heading. So for our purposes, in this case, Alabama stands alone.

Otherwise, the designations are based strictly on the combined scores of the rankings alone, with no attempt to account for injuries, transfers, academic casualties, arrests or any other routine form of attrition:

'Big Six' Conference Teams by Recruiting Class*

• FIVE-STAR (≤ 10,000 points): USC, Florida, Texas, Florida State, LSU, State" data-canon="Ohio Bobcats" data-type="SPORTS_OBJECT_TEAM" id="shortcode0">, Georgia, Oklahoma, Auburn, Notre Dame, Michigan.

• FOUR-STAR (6,000–9,999 points): Miami, Clemson, Tennessee, UCLA, Oregon, South Carolina, Texas A&M, Stanford, North Carolina, California, Ole Miss, Nebraska, Virginia Tech.

• THREE-STAR (4,000–5,999 points): Washington, Arkansas, Oklahoma State, Penn State, Michigan State, Texas Tech, Missouri, Arizona State, Maryland, Mississippi State, West Virginia, Rutgers, Pittsburgh, Utah, Virginia, Colorado, Arizona, TCU, NC State, Illinois.

• TWO-STAR (2,000–3,999 points): Minnesota, Iowa, Kansas, Louisville, Wisconsin, South Florida, Boston College, Baylor, Georgia Tech, Oregon State, Kansas State, Kentucky, BYU, Vanderbilt, Purdue.

• ONE-STAR (≥ 1,999 points): Cincinnati, Washington State, Duke, Northwestern, Syracuse, Indiana, Wake Forest, Iowa State, Connecticut, Temple.

- - -

* Based on Rivals' accumulated rankings, 2008-12.

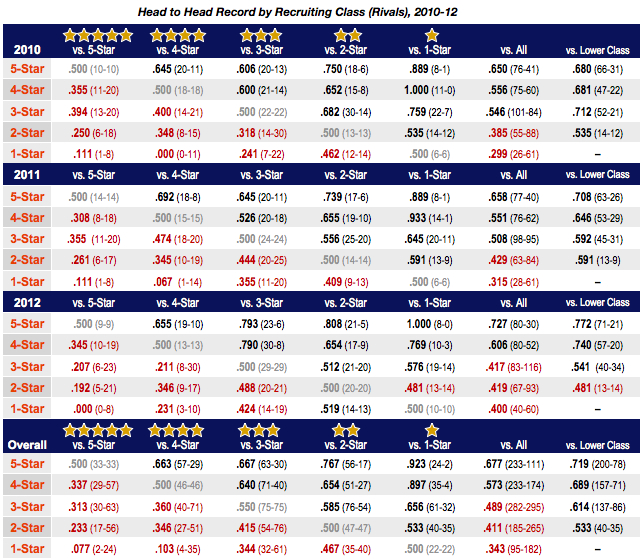

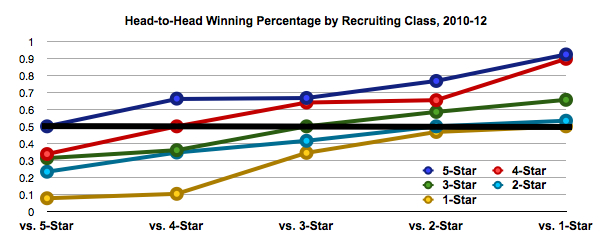

Over the past three years, those teams have played head-to-head 1,028 times. Here are the results of those games, with winning records in black and losing records in red:

To describe those results as "compelling" would be selling them short. It's a landslide:

On the final count, the higher-ranked team according to the recruiting rankings won almost exactly two-thirds of the time (66.4 percent of the time, to be exact), and every "class" as a whole had a winning record against every class ranked below it every single year. (The only exception, if it even qualifies, came last year, when "two-star" teams finished one game below .500 in head-to-head collisions with "one-star" teams. Elsewhere, the hierarchy held across every line.) The gap on the field also widened with the gap in the recruiting scores: At the extremes, "one-star" recruiting teams managed a grand total of six wins over "four-star" and "five-star" recruiters in 59 tries. Where a small handful of teams defied their rankings, none managed to do so as part of a larger group.

Which is, again, about as accurate as we can realistically expect from a system designed to predict an uncertain future.

So What? The evidence is overwhelming: Despite some obvious, anecdotal exceptions, on the whole recruiting rankings clearly are useful for creating a realistic baseline for expectations. But the narrower your focus, the less useful they will become.

The massively hyped, five-star recruit headlining your team's next recruiting class may be an irredeemable bust; he is also many times more likely than a scrappy three-star to pan out as an All-American and move on to the next level. Somewhere, an under-scouted afterthought with a chip on his shoulder will almost certainly go on to defy the odds, become a star and maybe win the Heisman Trophy. But that doesn't change the odds, which are against him becoming anything more than an obscure role player, at best. Inevitably, a team full of afterthoughts at the bottom of the rankings will defy the odds, catch fire, pull a few upsets and storm its way into a BCS bowl. But that doesn't change the odds, which are in favor of the same team dwindling on the edge of bowl eligibility. And just as inevitably, the eventual national champion will emerge from the ranks of the handful of teams that consistently come out on top on signing day.

The exceptions prove the rule: Overwhelmingly, setting aside every other conceivable factor that determines success and failure -- injuries, academics, even coaching -- individual players and teams tend to perform within the very narrow range their initial recruiting rankings suggest. Some percentage of both groups will not. But when it comes to forming expectations, it should go without saying that you never want to count on being one of the anomalies.